The human digestive system, especially the gut, plays a central role not only in digestion and nutrient absorption, but also in immunity, metabolism, and even mental health. In recent years, there has been a surge of scientific interest in the gut microbiome—the trillions of microbes inhabiting our intestines—and how its balance or imbalance (dysbiosis) can affect overall well-being.

In this article, we will explore:

- The anatomy and function of the digestive/gut system

- The gut microbiome: diversity, roles, and interactions

- When things go wrong: dysbiosis, gut disorders, and symptoms

- The gut-brain axis: how gut health ties into mental well-being

- Strategies to support and restore gut health

- Future directions and research frontiers

Before diving in, here is a helpful video overview:

1. Anatomy & Physiology of the Digestive Tract

The digestive tract—or gastrointestinal (GI) tract—extends from the mouth to the anus. Key segments include:

1.1 Basic Structure

- Mouth and esophagus: where food enters and is transported to the stomach

- Stomach: partially breaks down food by mechanical (churning) and chemical (acid, enzymes) action

- Small intestine (duodenum, jejunum, ileum): main site for digestion and nutrient absorption

- Large intestine / colon: absorbs water, electrolytes, and houses a dense microbial community

- Rectum and anus: store and excrete waste

Accessory organs (liver, gallbladder, pancreas) produce bile and digestive enzymes that act in the small intestine.

1.2 Function: Digestion, Absorption, Barrier

The gut has three core roles:

- Digestion & Absorption

Food is broken down into small molecules (amino acids, sugars, fatty acids, vitamins, minerals) and absorbed across the intestinal lining into the bloodstream or lymphatics. - Barrier & Immune Function

The gut forms a barrier that prevents pathogens and toxins from entering systemic circulation. The mucosal lining, tight junctions, mucus, secretory IgA, and immune cells all contribute to this. - Microbial Ecosystem & Metabolic Processing

The gut harbors a vast ecosystem of microorganisms (bacteria, fungi, viruses, archaea). These microbes ferment undigested fibers, produce metabolites (like short-chain fatty acids), synthesize vitamins, and influence host metabolism, immunity, and signaling throughout the body.

A disruption to any of these functions can ripple outward into systemic health effects.

2. The Gut Microbiome: Diversity, Dynamics & Roles

2.1 Microbial Diversity & Balance (Eubiosis)

A healthy gut microbiome is characterized by diversity—many different species of microbes in balanced proportions. This state is often referred to as eubiosis. In contrast, dysbiosis is a disturbed state marked by overgrowth of harmful species or loss of beneficial ones.

The diversity and composition are shaped by many factors: diet, age, genetics, medications (especially antibiotics), lifestyle, environment, stress, sleep, and more.

According to a comprehensive review, the gut microbiome exerts influences on immune, nervous, cardiometabolic systems by mediating diet–microbe interactions and nutrient signaling. (Nature)

Another review outlines how gut microbial balance or imbalance is implicated in conditions ranging from obesity and diabetes to inflammatory bowel disease and even mental disorders. (Frontiers)

2.2 Key Functional Roles of Gut Microbes

The gut microbes contribute to health via multiple pathways:

- Fermentation of dietary fiber & production of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs): Microbes ferment fibers and resistant starches to SCFAs like acetate, propionate, and butyrate, which nourish colon cells, reduce inflammation, modulate metabolism, and influence appetite.

- Synthesis of vitamins: Some microbes synthesize B-vitamins, vitamin K, and other micronutrients.

- Metabolism of xenobiotics and drugs: Microbes can activate, inactivate or modify medications and toxic compounds.

- Colonization resistance: Beneficial microbes competitively exclude pathogens, producing antimicrobial compounds and consuming available resources.

- Immune education & regulation: The gut microbiome educates the immune system, promoting tolerance to harmless antigens while mounting defense against pathogens.

- Communication & signaling: Microbiome-derived metabolites, peptides, and signals influence numerous remote organs (liver, brain, pancreas) and hormonal axes.

Hence, the microbiome acts as a virtual organ in its own right.

3. When Things Go Wrong: Dysbiosis & Gut Disorders

3.1 Causes of Dysbiosis

Several factors can upset microbial balance:

- Frequent antibiotic use

- Highly processed, low-fiber diet

- Chronic stress, poor sleep

- Infections

- Overuse of proton pump inhibitors or other acid suppressants

- Environmental toxins

- Sedentary lifestyle

Dysbiosis can reduce beneficial species, increase opportunistic/pathogenic species, and impair mucosal barrier integrity.

3.2 Clinical Manifestations & Gut Disorders

When gut health deteriorates, many symptoms and disorders can arise:

- Bloating, gas, flatulence

- Constipation or diarrhea

- Abdominal pain, cramping, discomfort

- Reflux, indigestion

- Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) including Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis

- Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO)

- Leaky gut / increased intestinal permeability

- Nutrient malabsorption, deficiencies

- Systemic inflammation, metabolic disturbances

Physicians often regard symptoms such as recurring bloating, abdominal pain, and altered bowel habits as warning signs that the microbiome might be disturbed. (American Medical Association)

Low-FODMAP diets, used to manage IBS symptoms by restricting fermentable carbohydrates, can sometimes help reduce symptoms but must be used cautiously because they may impair microbiome diversity if overused. (Wikipedia)

4. The Gut-Brain Axis & Systemic Effects

One of the most fascinating areas of modern research is the gut-brain axis: bi-directional communication between the gut (including microbes) and the brain (central nervous system). (Wikipedia)

4.1 Mechanisms of Gut-Brain Communication

Signals between the gut and brain travel via multiple routes:

- Neural pathways: The vagus nerve is a key highway transmitting gut signals to the brain.

- Endocrine / hormonal signaling: Gut microbes may influence hormonal mediators (e.g. ghrelin, leptin, cortisol) that affect appetite, mood, and stress responses.

- Immune / inflammatory pathways: Microbial metabolites and immune mediators (cytokines) may modulate systemic inflammation, affecting brain function.

- Microbial metabolites / neuroactive compounds: Certain microbes produce or modulate neurotransmitters or precursors (e.g. GABA, serotonin, dopamine) or microbial metabolites that cross into circulation.

Research suggests the gut microbiome can influence brain development, behavior, stress response, mood disorders, and cognition.

4.2 Systemic Impacts Beyond the Brain

Because the gut interacts intimately with metabolism, immunity, and inflammation, gut health is implicated in:

- Obesity, insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome

- Type 2 diabetes

- Cardiovascular disease

- Autoimmune disorders

- Liver disease (non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, NAFLD)

- Allergies, eczema, asthma

- Cancer risk, especially colorectal cancer

Thus, maintaining gut health is a cornerstone of holistic health.

5. Strategies to Support & Restore Gut Health

Given its central role, how can one nurture a healthy digestive gut? Below are evidence-based strategies.

5.1 Dietary Approaches

Eat whole, minimally processed foods

Whole grains, fruits, vegetables, legumes, nuts, seeds—all rich in fiber and phytonutrients—support microbial diversity. Processed foods high in refined sugars and additives may harm beneficial microbes. (Yale School of Medicine)

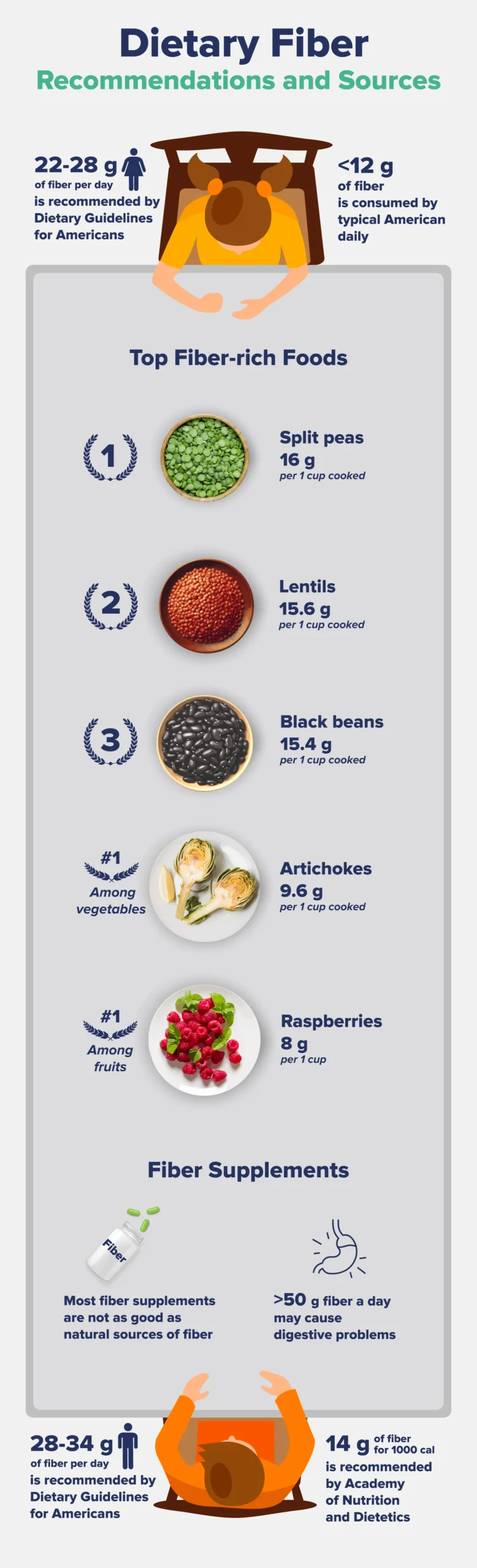

Increase dietary fiber & resistant starch

Fiber is the “food” for beneficial microbes. Diets rich in diverse fiber types stimulate SCFA production and colon health.

Include fermented & probiotic foods

Yogurt, kefir, kimchi, sauerkraut, miso, tempeh, and other fermented foods deliver live beneficial microbes and help maintain microbiome balance.

Prebiotic foods

Prebiotics are compounds (often fibers) that feed beneficial microbes. Examples include onion, garlic, leeks, asparagus, bananas, oats, chicory root.

Polyphenols & bioactive compounds

Foods rich in polyphenols—berries, green tea, dark chocolate, spices like turmeric—can support microbial diversity and anti-inflammatory effects.

Mindful use of low-FODMAP

For those with IBS or sensitive guts, a temporary low-FODMAP diet (under professional supervision) can reduce symptoms, but long-term use risks reducing microbial diversity. (Wikipedia)

5.2 Lifestyle & Behavioral Factors

- Manage stress: Chronic stress dysregulates gut motility, barrier function, and microbial balance. Practices like meditation, yoga, deep breathing, or biofeedback can help.

- Adequate sleep: Poor sleep quality is linked with altered microbiome and metabolic imbalance.

- Physical activity: Exercise is positively associated with greater microbial diversity, even independent of diet.

- Limit unnecessary antibiotics & medications: Antibiotics can devastate microbial populations. Use only when needed, and consider probiotic support.

- Avoid smoking, excessive alcohol, and artificial sweeteners: These are often correlated with poorer gut balance.

5.3 Probiotics, Prebiotics & Supplements

- Probiotics: These are live strains that may transiently colonize the gut and confer benefit (e.g. Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium). Their effects are strain-specific.

- Prebiotic fibers / oligosaccharides: These support growth of beneficial microbes.

- Synbiotics: Combinations of probiotics + prebiotics.

- Postbiotics / microbial metabolites: Emerging area—using beneficial metabolites directly rather than microbes.

- Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT): In severe dysbiosis cases (e.g. recurrent Clostridioides difficile), transplanting microbiota from healthy donors has shown success; research continues for broader applications.

5.4 Clinical Interventions & Monitoring

- Diagnostic testing: Stool microbiome profiling, breath tests (for SIBO), gut permeability assays, and endoscopy/colonoscopy when indicated.

- Targeted therapies: For IBD, IBS, SIBO, and other gut disorders, medications, diet modifications, and microbial therapies may be used in combination.

- Stepwise reintroduction protocols: After using restrictive diets (e.g. low-FODMAP), reintroduce fiber groups gradually to maintain diversity.

5.5 Practical Tips & Habits

- Try to eat a “rainbow” of plant foods (diverse colors) to support a broad microbiome.

- Chew your food thoroughly (starts digestion early, supports microbiome).

- Stay well-hydrated—fluids help move contents through the gut.

- Practice regular meal timing—consistent eating patterns support gut rhythm.

- Avoid eating late at night if possible (circadian rhythm influences gut).

- If using probiotics, choose high-quality, well-studied strains and take them with food (unless otherwise instructed).

Harvard Health outlines “5 simple ways to improve gut health,” emphasizing diet, sleep, activity, and avoidance of unnecessary medications. (Harvard Health)

6. Future Directions & Frontiers

6.1 Precision Microbiome-Based Nutrition

Because individuals respond differently to foods (based on genetics, microbiome composition, etc.), the future likely lies in personalized nutrition—diets tailored to one’s microbial profile to optimize health outcomes. (Nature)

6.2 Microbial Therapeutics & Engineered Probiotics

Researchers are engineering bacteria to produce therapeutic molecules (anti-inflammatory peptides, satiety signals, etc.). Microbial “drugs” may be the next frontier.

6.3 Metabolomics & Postbiotic Therapies

Studying microbial metabolites (SCFAs, secondary bile acids, indoles, etc.) may yield direct therapeutic compounds (“postbiotics”) that bypass needing live microbes.

6.4 Gut–Organ Axes Beyond the Brain

Beyond the gut-brain axis, there is growing exploration of gut–lung, gut–skin, gut–liver, gut–heart axes, implying that gut health may influence many other organ systems.

6.5 Longitudinal & Interventional Human Studies

Many current studies are cross-sectional or short-term. Longer-term human trials are needed to prove causality and effective interventions.

Conclusion

Your gut is far more than a food-processing tube. It’s a complex ecosystem, immune barrier, metabolic hub, and communication center. A healthy gut microbiome is essential for digestion, nutrient absorption, immune function, metabolic balance, and even mental health.

Unfortunately, modern lifestyle factors—highly processed diets, stress, antibiotics, sedentary habits—pose threats to gut balance. But the good news is that many practices can support or restore gut health: whole-food diets, fiber-rich and fermented foods, stress regulation, physical activity, and thoughtful use of microbial therapies.

Whether you’re aiming to address occasional bloating or chronic gut issues, a holistic, evidence-based approach gives you the best chance of nurturing a resilient, vibrant digestive system.

References (two key sources):

- Harvard Health – 5 simple ways to improve gut health (Harvard Health)

- Frontiers review on human gut microbiota in health and disease (Frontiers)