Introduction: That Feeling in Your Gut Isn’t Just in Your Head

If you’ve ever felt “butterflies” before a first date, experienced a “gut-wrenching” loss, or had a “knot” in your stomach during a stressful workweek, you’ve already had a personal introduction to one of the most exciting frontiers in modern medicine: the gut-brain axis.

For decades, the connection between our digestive system and our emotions was dismissed as folk wisdom or mere metaphor. Anxiety was considered a condition of the mind alone, treated primarily through therapy and medications that targeted the brain. Meanwhile, digestive issues like Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) were often relegated to the realm of psychosomatic illness, leaving millions of patients feeling misunderstood.

Today, a seismic shift is underway. A convergence of research in neurogastroenterology, microbiology, and psychiatry is proving that these “gut feelings” are not just figurative language—they are biological reality. The gut and the brain are in constant, intimate communication, and the trillions of microbes residing in our intestines hold a surprising amount of influence in this conversation.

This article will delve into the intricate science of the gut-brain axis, unraveling its powerful connection to the rising rates of anxiety in the United States. We will move beyond the hype to provide an evidence-based exploration of how your digestive health directly impacts your mental well-being and offer a practical, actionable roadmap for cultivating a calmer mind through a healthier gut.

Part 1: The Anatomy of the Conversation – Meet the Key Players

To understand how your gut can influence your anxiety, we must first meet the biological structures and entities facilitating this conversation.

1.1 The Vagus Nerve: The Information Superhighway

The most direct line of communication between the gut and the brain is the vagus nerve. This long, wandering cranial nerve (its name comes from the Latin for “wandering”) stretches from the brainstem down to the colon, connecting to the heart, lungs, and most major organs along the way.

- Function: It is the primary component of the parasympathetic nervous system, often called the “rest-and-digest” system, which counteracts the “fight-or-flight” stress response.

- The Gut-Brain Link: An estimated 80-90% of the nerve fibers in the vagus nerve are afferent, meaning they carry signals from the gut to the brain. Your gut is constantly sending a stream of information about its state—fullness, nutrient content, inflammation, and microbial activity—up to your brain, which interprets this data and influences your mood and emotional state.

Read more: Rise of Probiotics, Prebiotics, and Synbiotics: America’s Gut Health Revolution

1.2 The Enteric Nervous System (ENS): The “Second Brain” in Your Gut

Often called the body’s “second brain,” the Enteric Nervous System (ENS) is a vast and complex network of over 100 million neurons embedded in the sheaths of tissue lining your esophagus, stomach, small intestine, and colon.

- Function: The ENS can operate independently from the brain and spinal cord (the central nervous system). It manages the entire digestive process: swallowing, releasing enzymes, controlling blood flow for nutrient absorption, and eliminating waste.

- The Gut-Brain Link: The ENS doesn’t just handle digestion. It communicates bidirectionally with the central nervous system (CNS) via the vagus nerve and other pathways. This is why mental stress can trigger digestive upset (brain to gut), and why gastrointestinal distress can cause anxiety or depression (gut to brain).

1.3 The Gut Microbiota: The Tiny Power Brokers

This is perhaps the most revolutionary player in the story. Your gut is home to a vast ecosystem of trillions of microorganisms—bacteria, viruses, fungi, and other microbes—collectively known as the gut microbiota. The collective genetic material of these microbes is the microbiome.

- Function: These microbes are essential for digesting fiber, producing certain vitamins (like B12 and K), training our immune system, and protecting against pathogenic bacteria.

- The Gut-Brain Link: Gut microbes don’t just passively live in our intestines; they are active chemical factories. They produce a plethora of neuroactive compounds that directly influence brain function. The composition and health of your gut microbiota play a decisive role in this communication.

1.4 Neurotransmitters: The Chemical Messengers

You might think of neurotransmitters like serotonin and dopamine as being exclusively produced in the brain. But a significant portion of these critical mood-regulating chemicals are actually manufactured in the gut.

- Serotonin: Often called the “happiness molecule,” approximately 90% of the body’s serotonin is produced in the digestive tract, primarily by enterochromaffin cells and certain gut bacteria. Gut serotonin is crucial for regulating intestinal motility, but it also communicates with the brain via the vagus nerve, influencing mood, sleep, and appetite.

- GABA (Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid): This is the brain’s primary “calming” neurotransmitter, counteracting anxiety. Certain strains of beneficial gut bacteria, like Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium, have been shown to produce GABA.

- Dopamine & Others: Gut microbes also contribute to the production of dopamine (involved in motivation and reward) and other neurotransmitters like norepinephrine.

Part 2: The Anxiety Connection – How a Distressed Gut Creates a Distressed Mind

Now that we know the players, let’s examine the specific mechanisms through which a disrupted gut can fuel clinical anxiety.

2.1 The Inflammatory Pathway: When the Body Sounds the Alarm

Chronic, low-grade systemic inflammation is a key physiological state linked to both depression and anxiety. The gut plays a central role in regulating inflammation throughout the body.

- Leaky Gut (Intestinal Permeability): When the gut is unhealthy—due to a poor diet, chronic stress, or antibiotics—the single layer of cells lining the intestinal wall can become damaged and “leaky.” This allows bacterial fragments (like LPS – Lipopolysaccharide) and other undigested food particles to pass into the bloodstream.

- The Immune Response: The immune system identifies these foreign particles as threats and launches an inflammatory attack. This inflammation produces cytokines, chemical messengers that can travel to the brain.

- Impact on the Brain: In the brain, these inflammatory cytokines can disrupt the production and signaling of key neurotransmitters like serotonin. They can also impact the function of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, the body’s central stress response system, leading to elevated cortisol levels and heightened anxiety.

2.2 The Microbial Metabolite Pathway: Direct Chemical Influence

As mentioned, gut microbes produce neuroactive compounds. An imbalance in the gut ecosystem, known as dysbiosis (an overgrowth of harmful microbes and a reduction in beneficial ones), can directly alter the production of these chemicals.

- Scenario: A diet high in processed foods and sugar feeds pro-inflammatory bacteria while starving the beneficial, fiber-fermenting ones. This dysbiotic community produces fewer calming compounds like GABA and butyrate (an anti-inflammatory short-chain fatty acid) and may produce more chemicals that stimulate the nervous system.

- Result: The chemical signals being sent up the vagus nerve to the brain shift from “all is well” to “system under threat,” priming the brain for a state of anxiety and hyper-vigilance.

2.3 The Vagus Nerve Pathway: Toning the Communication Cable

The vagus nerve’s tone—its level of activity—is crucial for resilience to stress. A high vagal tone is associated with better mood, lower inflammation, and a quicker recovery from stressful events. Crucially, the health of your gut microbiota directly influences vagal tone.

- Studies have shown: that certain probiotic strains (often called “psychobiotics”) can exert anti-anxiety effects, but only if the vagus nerve is intact. When the nerve is severed in animal studies, the calming effects of the probiotics disappear. This proves the vagus nerve is a critical pathway for gut microbes to signal the brain.

Part 3: The American Context – Why is This Relevant Now?

The gut-brain axis isn’t a new discovery, but its relevance has exploded in parallel with the rise of mental health disorders and chronic digestive issues in the US.

- The Standard American Diet (SAD): Characterized by high levels of ultra-processed foods, refined sugars, unhealthy fats, and low levels of dietary fiber, the SAD is a primary driver of gut dysbiosis. It starves the beneficial microbes that need fiber to produce anti-inflammatory compounds.

- The Chronic Stress Epidemic: High-pressure jobs, financial worries, and 24/7 digital connectivity keep the body in a constant state of low-grade “fight-or-flight.” This stress directly impacts gut motility, reduces blood flow to the intestines, and alters the microbial composition, creating a vicious cycle: stress damages the gut, and the damaged gut exacerbates stress.

- Overuse of Medications: While sometimes life-saving, the widespread use of antibiotics can decimate beneficial gut bacteria. Other common medications like non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and proton pump inhibitors can also damage the gut lining.

Part 4: Healing from the Gut Up – An Evidence-Based Action Plan

The most empowering aspect of this science is that it gives us a new, tangible set of tools to manage anxiety. By healing the gut, we can positively influence the brain.

4.1 Feed Your Microbes: The Power of Prebiotics

Prebiotics are types of dietary fiber that act as food for your beneficial gut bacteria. They are arguably more important than probiotics for long-term microbial health.

- Sources: Garlic, onions, leeks, asparagus, bananas, oats, apples, flaxseeds, and Jerusalem artichokes.

- Goal: Aim for a diverse array of plants in your diet. A good target is 30 different plant-based foods per week, which has been linked to a more diverse microbiome.

4.2 Incorporate Beneficial Bacteria: The Role of Probiotics & Fermented Foods

Probiotics are live bacteria that can confer a health benefit when consumed.

- Fermented Foods: Include unsweetened yogurt, kefir, sauerkraut, kimchi, kombucha, and miso in your diet. These provide a diverse array of live cultures.

- Psychobiotic Supplements: Specific probiotic strains have shown promise in clinical studies for reducing anxiety and perceived stress. Look for strains like Lactobacillus helveticus R0052, Bifidobacterium longum R0175, and Lactobacillus rhamnosus JB-1. Always consult with a healthcare provider before starting a new supplement, especially if you have a compromised immune system.

4.3 The Gut-Healing Diet: Anti-Inflammatory Principles

Shift your overall eating pattern to reduce inflammation and support the gut lining.

- Emphasize: Omega-3 fatty acids (fatty fish, walnuts, flaxseeds), colorful fruits and vegetables (rich in polyphenols and antioxidants), and high-quality protein.

- Reduce/Minimize: Ultra-processed foods, refined sugars, industrial seed oils (soybean, corn, canola), and artificial sweeteners, which can negatively impact gut bacteria.

4.4 Lifestyle Interventions that Support the Axis

- Manage Stress with Mind-Body Practices: Techniques like meditation, deep breathing, and yoga have been shown to improve gut symptoms and increase vagal tone, directly enhancing the gut-brain connection.

- Prioritize Sleep: Poor sleep disrupts the gut microbiome, and a disrupted microbiome can lead to poor sleep. Aim for 7-9 hours of quality sleep per night to support this delicate cycle.

- Move Your Body: Regular, moderate exercise has been shown to increase the diversity of beneficial gut microbes and is a powerful anti-anxiety tool.

When to Seek Professional Help

This information is empowering, but it is not a substitute for professional medical care.

You should consult a healthcare provider if you are experiencing:

- Clinical anxiety or depression that interferes with your daily life.

- Persistent digestive symptoms like chronic bloating, pain, diarrhea, or constipation (to rule out conditions like IBS, IBD, or SIBO).

- Before making drastic changes to your diet or starting a new supplement regimen.

A qualified professional, such as a gastroenterologist, a registered dietitian specializing in gut health, or a functional medicine doctor, can help you create a personalized plan.

Conclusion: Embracing the Wisdom of the Whole Body

The science of the gut-brain axis invites us to a more holistic view of health. It tells us that mental well-being cannot be separated from physical well-being, and that the food we eat is more than just fuel—it is information for our bodies and a source of medicine for our minds.

The phrase “gut feeling” is a testament to an ancient, intuitive wisdom that modern science is now validating. By listening to our guts—not just as a source of metaphor, but as a biological center of gravity for our health—we can open up new, powerful pathways to managing anxiety and cultivating resilience. The path to a calmer mind, it turns out, may very well begin in the gut.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q1: If I have anxiety, should I just take a probiotic supplement?

Probiotics can be a helpful tool, but they are not a magic bullet. The most effective approach is holistic. Focus on building a gut-healthy lifestyle with a diverse, fiber-rich diet, stress management, and good sleep. If you choose a supplement, look for well-researched strains and consult with a healthcare professional. Think of probiotics as one piece of a much larger puzzle.

Q2: How long does it take to see an improvement in my anxiety by changing my gut health?

This varies significantly from person to person. Some people may notice subtle improvements in mood and digestion within a few weeks of consistent dietary and lifestyle changes. For others, especially those with long-standing gut issues or anxiety, it may take several months of dedicated effort to see significant results. Patience and consistency are key.

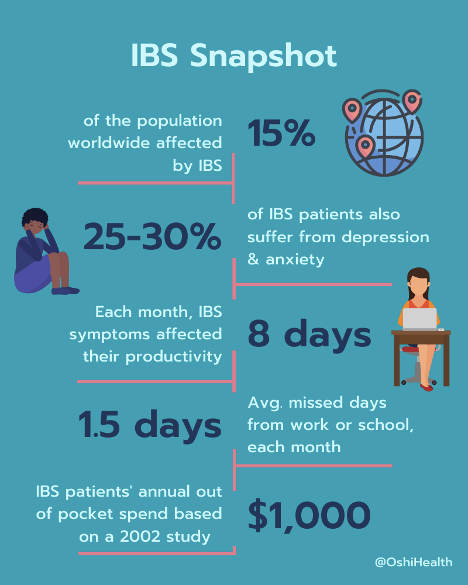

Q3: I have IBS and anxiety. Is one causing the other?

This is the quintessential “chicken or egg” scenario of the gut-brain axis. In many cases, it’s a vicious cycle. Stress and anxiety can trigger or worsen IBS symptoms (brain to gut). Simultaneously, the chronic discomfort, pain, and inflammation of IBS can be a constant source of stress and anxiety (gut to brain). Treating both conditions together—often with a combination of dietary therapy, gut-directed hypnotherapy, and stress management—is the most effective strategy.

Q4: Are there any specific tests I can take to check my gut microbiome?

Direct-to-consumer microbiome testing kits are available and can provide a snapshot of the bacterial composition in your stool. However, it’s important to interpret these results with caution. The science is still young, and these tests cannot yet provide definitive diagnoses or specific treatment plans for mental health conditions. They can be interesting for educational purposes, but the best “test” is often to see how your body and mind respond to evidence-based lifestyle interventions.

Q5: Can improving my gut health allow me to stop taking my anxiety medication?

Absolutely not. Do not stop or change the dosage of any prescribed medication without the direct supervision and guidance of your prescribing doctor. The goal of supporting gut health is to be a complementary strategy to enhance your overall well-being and resilience. It is a powerful form of self-care that works alongside, not in place of, professional medical treatment.

Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only and is based on current scientific research and clinical understanding. It is not intended to provide medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician, registered dietitian, or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition. Never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read in this article.

Read more: Herbal and Natural Remedies for Gut Health