Introduction

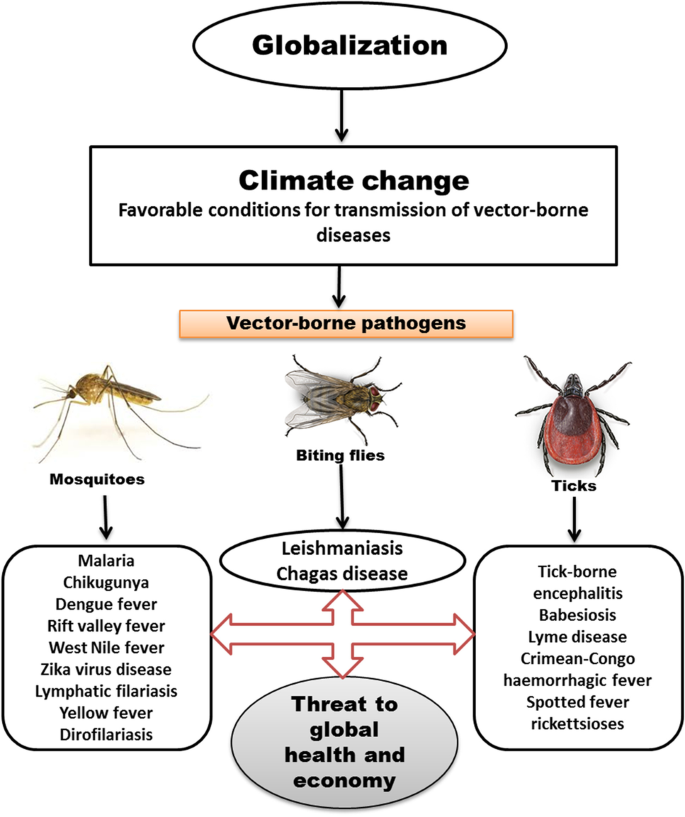

For decades, the American public health landscape has been shaped by a silent, creeping threat. Unlike pandemics that arrive with sudden, explosive force, this danger has advanced steadily, mile by mile, season by season. It is the threat of vector-borne diseases—illnesses transmitted by ticks and mosquitoes. Among the most pervasive and concerning of these are Lyme disease and West Nile virus (WNV). Once considered regional nuisances, these diseases have expanded their geographical reach and intensified their impact, evolving into a nationwide public health challenge.

This expansion is not accidental. It is fueled by a complex interplay of climate change, land-use patterns, wildlife population dynamics, and human behavior. Understanding this interplay is critical to developing effective strategies for prevention, diagnosis, and treatment. This article delves deep into the resurgent threats of Lyme disease and West Nile virus in the United States. We will explore the science behind their spread, the current epidemiological landscape, the significant public health and economic burdens they impose, and the multifaceted strategies required to mitigate their impact. By synthesizing the latest research and expert insights, this analysis aims to provide a authoritative resource for understanding one of the most significant environmental health issues of our time.

Part 1: Lyme Disease – The Expanding Shadow of the Tick

The Pathogen and the Vector

Lyme disease is caused by the spirochete bacterium Borrelia burgdorferi and, in some cases, other related Borrelia species. It is transmitted to humans primarily through the bite of infected black-legged ticks, often called deer ticks.

- The Vector’s Life Cycle: Understanding the tick’s life cycle is key to understanding Lyme disease risk. Black-legged ticks have a two-year, three-stage life cycle: larva, nymph, and adult.

- Larvae: Hatch uninfected and typically acquire the Borrelia bacteria by feeding on an infected small animal, most commonly the white-footed mouse, which serves as the primary reservoir.

- Nymphs: This is the most critical stage for human transmission. Nymphs are tiny (poppy-seed sized), making them difficult to spot, and are most active during the spring and summer months when human outdoor activity is high.

- Adults: Larger and more easily seen, adult ticks can also transmit the disease. They are most active in the cooler fall and spring months.

- Transmission Dynamics: A tick must be attached for 36 to 48 hours to transmit the Borrelia bacterium. This provides a critical window for prevention through daily tick checks.

The Dramatic Geographical Expansion

Historically confined to the Northeast and upper Midwest, Lyme disease has seen a dramatic territorial expansion over the past two decades.

- Data-Driven Evidence: According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the number of counties in the northeastern United States considered to have a high incidence of Lyme disease increased by more than 320% between 1993 and 2012. This expansion has spread southward into Virginia and the Carolinas and northward into Canada.

- Key Drivers of Expansion:

- Climate Change: Warmer temperatures and shorter winters extend the active feeding season for ticks. Milder winters also increase the survival rates of both ticks and their rodent hosts.

- Land Fragmentation and Reforestation: Suburban development creates “edge habitats,” the border zones between forests and grasslands that are ideal for the white-footed mouse and the ticks it hosts. The decline of natural predators in these areas further allows rodent populations to thrive.

- Wildlife Corridors: The proliferation of white-tailed deer, which are key reproductive hosts for adult ticks (though not competent reservoirs for the bacteria), has facilitated the movement of ticks into new areas. Deer act as taxis, transporting thousands of reproductive adult ticks across the landscape.

Clinical Presentation and Diagnostic Challenges

Lyme disease is notoriously difficult to diagnose, earning it the label of “the great imitator.”

- Early Localized Disease (3-30 days post-tick bite):

- The hallmark sign is Erythema Migrans (EM), a “bull’s-eye” rash that occurs in approximately 70-80% of infected persons. It expands gradually and is rarely itchy or painful.

- Flu-like symptoms: fever, chills, fatigue, body aches, and headache.

- Early Disseminated Disease (days to weeks post-bite):

- The bacteria have spread throughout the body.

- Symptoms can include severe headaches, additional EM rashes, facial palsy (loss of muscle tone on one or both sides of the face), arthritis with severe joint pain and swelling, heart palpitations or Lyme carditis, and dizziness.

- Late Disseminated Disease (months to years post-bite):

- Approximately 60% of untreated patients develop intermittent bouts of arthritis, with particular focus on the knees.

- Neurological issues can include shooting pains, numbness, tingling in the hands or feet, and problems with short-term memory.

- The Diagnostic Dilemma: The two-tiered serological testing (ELISA followed by Western Blot) recommended by the CDC has limitations. Antibodies can take several weeks to develop, leading to false negatives in the early stages of infection. Furthermore, the test cannot distinguish between an active, current infection and a past, resolved one. Diagnosis must therefore be based on a combination of symptoms, potential exposure, and laboratory findings, often requiring a physician experienced in tick-borne illnesses.

Treatment and the Controversy of “Chronic Lyme”

- Standard Treatment: The vast majority of Lyme disease cases are cured with a 2-4 week course of oral antibiotics, such as doxycycline or amoxicillin. Intravenous antibiotics may be used for more severe cases, particularly those involving the central nervous system or heart.

- Post-Treatment Lyme Disease Syndrome (PTLDS): A subset of patients (estimated 10-20%) experience lingering symptoms like fatigue, pain, or cognitive difficulties after completing antibiotic treatment. The cause of PTLDS is not well understood but is thought to be an autoimmune response or residual damage to tissues, not a persistent, active infection.

- “Chronic Lyme” Controversy: This term is often used by patients and some advocacy groups to describe a persistent Borrelia infection requiring long-term antibiotic treatment. However, this diagnosis is not recognized by major medical organizations like the CDC or the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA), as multiple rigorous clinical trials have shown that long-term antibiotics are not beneficial and can cause significant harm. This disconnect has created a deep schism between many patients and the medical establishment, highlighting the need for more research into the underlying mechanisms of persistent symptoms.

Read more: The Return of RSV, Flu & Respiratory Coinfections: What to Expect This Season

Part 2: West Nile Virus – The Ubiquitous Mosquito-Borne Threat

The Pathogen and the Vector

West Nile virus is a flavivirus most commonly spread to humans through the bite of an infected Culex species mosquito.

- The Transmission Cycle: The virus is maintained in a bird-mosquito-bird cycle. Mosquitoes become infected when they feed on infected birds. They can then transmit the virus to humans and other “dead-end” hosts, meaning these hosts do not develop enough virus in their bloodstream to reinfect mosquitoes.

- Primary Vectors: Several Culex species are the primary vectors in the U.S., including Culex pipiens (the northern house mosquito) in the Northeast and Midwest, Culex quinquefasciatus (the southern house mosquito) in the South, and Culex tarsalis in the West. These mosquitoes are often most active from dusk to dawn.

National Colonization and Seasonal Variability

Since its first identification in New York City in 1999, West Nile virus spread rapidly across the continental United States within just a few years. It is now the leading cause of mosquito-borne disease in the country.

- Widespread Presence: As of today, WNV has been detected in all 48 contiguous states. The intensity of transmission, however, varies dramatically from year to year and region to region.

- Epidemiological Patterns: Outbreaks are often localized and unpredictable, heavily influenced by:

- Climate: Heat waves accelerate the virus replication within the mosquito and shorten the incubation period. Fluctuations in rainfall can create or destroy mosquito breeding sites.

- Bird Reservoir Dynamics: The immunity levels in local bird populations can influence the intensity of transmission.

- Human Activity: Outdoor activities during peak mosquito hours increase exposure risk.

Spectrum of Clinical Illness

Approximately 80% of people infected with WNV will be asymptomatic. About 1 in 5 will develop West Nile fever, and a much smaller fraction will develop severe neuroinvasive disease.

- West Nile Fever (~20% of cases): A febrile illness characterized by headache, body aches, joint pains, vomiting, diarrhea, or a rash. Fatigue and weakness can last for weeks or months.

- Neuroinvasive Disease (~1 in 150 cases): The virus crosses the blood-brain barrier, leading to serious neurological conditions. This includes:

- West Nile Encephalitis: Inflammation of the brain.

- West Nile Meningitis: Inflammation of the membranes surrounding the brain and spinal cord.

- Acute Flaccid Paralysis: A polio-like syndrome involving sudden weakness and paralysis of the limbs or respiratory muscles.

- Long-Term Outcomes and Fatality: Recovery from severe neuroinvasive disease can be prolonged and incomplete. Neurological deficits may be permanent. Among patients with neuroinvasive disease, approximately 10% die. The risk of severe disease increases significantly with age and in immunocompromised individuals.

Diagnosis, Treatment, and Prevention

- Diagnosis: Diagnosis is typically confirmed by detecting WNV-specific IgM antibodies in serum or cerebrospinal fluid. The presence of IgM antibodies generally indicates a recent infection.

- Treatment: There are no antiviral drugs or specific human treatments for WNV. Care is supportive, often involving hospitalization, intravenous fluids, respiratory support, and prevention of secondary infections.

- Prevention is Paramount: With no specific treatment, public health efforts are overwhelmingly focused on prevention through:

- Public Education: Using EPA-registered insect repellent, wearing long sleeves and pants, and installing window screens.

- Mosquito Control: Local abatement districts conduct larval surveillance and control (larviciding) in standing water and adult mosquito control (adulticiding) when necessary.

- Community Action: Encouraging residents to eliminate standing water around their homes (e.g., in flower pots, buckets, and old tires).

Part 3: Converging Drivers and Public Health Response

The parallel expansions of Lyme disease and West Nile virus are not coincidental. They share several common drivers that public health officials must address in an integrated manner.

- Climate Change as a Key Amplifier: A warmer climate extends the seasonal activity of both ticks and mosquitoes, increases their geographical range northward and to higher elevations, and accelerates the replication of pathogens within them.

- Urbanization and Land Use: The creation of suburban and peri-urban environments provides ideal ecotones for the wildlife and vectors that carry these diseases.

- The Challenge of Surveillance: Robust surveillance is the bedrock of public health response. This includes:

- For Lyme: Tracking human cases, testing ticks for pathogens, and monitoring animal reservoirs.

- For WNV: Monitoring dead birds (an early warning sign), testing mosquito pools for the virus, and tracking human cases.

- Data Gaps: Underreporting is a significant issue for both diseases, particularly for Lyme, where diagnosis is challenging.

The Economic and Societal Burden

The cost of these diseases is staggering, extending far beyond the healthcare system.

- Direct Medical Costs: Doctor visits, laboratory testing, emergency room care, hospitalization, and long-term antibiotic or supportive therapy.

- Indirect Costs: Lost productivity from missed work (for both patients and caregivers), long-term disability, and reduced quality of life.

- A Study in Costs: A 2018 study published in the Journal of Medical Economics estimated the average lifetime cost per patient of Lyme disease could be as high as $25,000-$50,000 when accounting for PTLDS. The annual economic burden of acute WNV illness in the U.S. was estimated to be $56 million, with neuroinvasive disease accounting for the vast majority of costs.

The Future of Vector-Borne Disease Control

Combating these expanding threats requires innovation and a multi-pronged approach:

- Next-Generation Personal Protection: Beyond repellents, research into treated clothing and new spatial repellent technologies is ongoing.

- Environmental Management: Targeted acaricide (tick pesticide) applications, deer population management, and community landscaping guidelines to reduce tick habitats.

- Biotechnological Interventions:

- For Lyme: A new human Lyme vaccine candidate is in late-stage clinical trials, offering hope for the future.

- For WNV: Research continues on a human vaccine, though none is currently available. Novel approaches include releasing Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes, which can suppress Culex populations or inhibit the virus’s ability to replicate inside the mosquito.

- Integrated Public Health Education: Consistent, clear messaging from local, state, and federal health departments is crucial. The public needs to understand the specific risks in their area and the simple, effective steps they can take to protect themselves.

Conclusion

The expansion of Lyme disease and West Nile virus across the United States is a clear and present public health crisis. It is a story written by the interplay of our changing climate, our transformed landscapes, and the complex biology of the vectors that thrive within them. There is no single solution. Success will depend on a sustained, sophisticated, and well-funded effort that integrates surveillance, research, innovation, and, most importantly, public awareness. As these vectors continue to advance into new territories, the responsibility falls upon individuals, communities, and health agencies to remain vigilant. The bite of a tick or a mosquito is no longer a minor nuisance; it is a potential encounter with a significant and growing health threat, one that demands our respect and our proactive defense.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q1: I found a tick attached to me. What should I do immediately?

- A: Do not panic. Use fine-tipped tweezers to grasp the tick as close to the skin’s surface as possible. Pull upward with steady, even pressure. Do not twist or jerk, as this can cause mouth-parts to break off. After removing the tick, thoroughly clean the bite area and your hands with rubbing alcohol or soap and water. Flush the tick down the toilet or, if you wish to have it tested, place it in a sealed bag or container. Note the date of the bite.

Q2: Should I get the tick tested for Lyme disease?

- A: The CDC does not recommend testing individual ticks for several reasons. A positive test does not necessarily mean you were infected, and a negative test might give false reassurance if the tick was attached long enough but was not carrying that specific pathogen. It is more important to monitor your health for symptoms and contact your healthcare provider promptly if any develop, informing them of the tick bite.

Q3: Is there a vaccine for Lyme disease or West Nile virus for humans?

- A: For Lyme disease, there is currently no vaccine available for humans in the U.S. (One existed in the early 2000s but was discontinued). However, a new Lyme vaccine candidate is in advanced clinical trials and shows promise. For West Nile virus, there is also no human vaccine currently on the market, though several are in various stages of development. Vaccines exist for horses, which are also susceptible to WNV.

Q4: I had Lyme disease and finished my antibiotics, but I still feel tired and achy. Is this “Chronic Lyme”?

- A: The medical term for these persistent symptoms is Post-Treatment Lyme Disease Syndrome (PTLDS). The exact cause is unknown, but it is not believed to be due to an ongoing, active infection that requires long-term antibiotics. Management focuses on treating specific symptoms, such as pain relievers for arthritis or cognitive behavioral therapy for fatigue. It is essential to work with a healthcare provider to rule out other potential causes for your symptoms.

Q5: Can I get West Nile virus from a dead bird?

- A: The primary route of infection is through a mosquito bite. You cannot get WNV from touching or handling a live or dead bird. However, you should avoid bare-handed contact with any dead animal. Use gloves or a plastic bag to place the bird in a garbage bag for disposal. Reporting dead birds (especially crows, jays, and raptors) to your local health department can be a valuable part of public health surveillance.

Q6: Are some people more at risk for severe illness from these diseases?

- A: Yes. For Lyme disease, risk is primarily behavioral and geographical—those who spend time in wooded or grassy areas in endemic regions are at highest risk. For West Nile virus, the risk of developing severe neuroinvasive disease increases significantly for people over 60 years of age and for individuals with certain medical conditions, such as cancer, diabetes, hypertension, and kidney disease, or those who are immunocompromised.

Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only and is based on current scientific understanding and guidelines from authoritative bodies like the CDC and IDSA. It is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition.

Read more: Chagas Disease in the U.S.: 10 Alarming Facts About the Kissing Bug Epidemic