In the landscape of American health, few crises are as pervasive and preventable as the type 2 diabetes epidemic. Affecting over 38 million Americans (according to the CDC), with an additional 98 million adults living with prediabetes, this metabolic disorder has become a defining public health challenge of our time. For decades, the conversation around its cause was narrowly focused on sugar and obesity. While these are critical pieces of the puzzle, a deeper, more systemic culprit has emerged from the shadows of our pantries and refrigerators: the overwhelming reliance on ultra-processed foods.

This is not merely about the occasional indulgence in a bag of chips or a sugary soda. This is about a fundamental shift in the American diet, where the majority of calories for nearly 60% of US adults now come from a category of engineered edible substances that are far removed from whole, natural food. These ultra-processed foods (UPFs) are not just “junk food.” They are complex concoctions of industrial ingredients, designed for hyper-palatability, long shelf life, and profit maximization, and they are actively disrupting our metabolism in profound ways.

This article will dissect the intricate link between the rise of UPFs and the surge in type 2 diabetes. We will move beyond simplistic calories-in-calories-out models to explore the science of how these food-like products manipulate our hormones, gut health, and brain chemistry to drive insulin resistance and, ultimately, a diagnosis that changes lives. More importantly, we will provide a clear, evidence-based pathway back to metabolic health, empowering you with the knowledge to make informed choices for yourself and your family.

Section 1: Understanding the Enemy – What Exactly Are Ultra-Processed Foods?

To comprehend their impact, we must first clearly define what we are talking about. The NOVA classification system, developed by an international panel of food scientists and public health researchers, is the gold standard for categorizing foods based on the extent and purpose of their processing. It divides foods into four groups:

- Unprocessed or Minimally Processed Foods: These are the edible parts of plants (fruits, vegetables, seeds, nuts) and animals (muscle, offal, eggs, milk). Minimal processes include cleaning, removal of inedible parts, pasteurization, freezing, or fermentation that doesn’t add substances.

- Processed Culinary Ingredients: These are substances derived from Group 1 foods by pressing, refining, grinding, or milling. Examples include oils, butter, sugar, salt, and maple syrup. They are not meant to be eaten alone but used to prepare and cook Group 1 foods.

- Processed Foods: These are simple products made by adding Group 2 ingredients (salt, sugar, oil) to Group 1 foods to enhance their durability or palatability. Examples include canned vegetables in brine, canned fish in oil, freshly made cheeses, and simple breads. They typically contain two or three ingredients.

- Ultra-Processed Foods (UPFs): This is the critical category. UPFs are industrial formulations typically containing five or more ingredients that are not commonly used in home cooking. These include substances like:

- Hydrolyzed proteins: Used to mimic the taste and mouthfeel of protein.

- Maltodextrin: A rapidly digested carbohydrate from starch.

- High-fructose corn syrup (HFCS): A cheap, intensely sweet liquid sugar.

- Hydrogenated or interesterified oils: Industrially created fats designed for shelf stability.

- Emulsifiers (e.g., lecithin, mono- and diglycerides): To mix water and oil.

- Artificial colors, flavors, and sweeteners: To create a sensory experience that real food cannot match.

- Bulking agents and anti-foaming agents: For texture and manufacturing ease.

Key Takeaway: UPFs are not “modified” foods; they are formulations of ingredients, mostly of exclusive industrial use. Their primary purpose is to be highly profitable, convenient, and hyper-palatable, often displacing whole foods and home-cooked meals.

Common examples saturating the American diet include:

- Soft drinks and sugary juices

- Mass-produced packaged breads and buns

- Sweetened breakfast cereals and cereal bars

- Instant noodles and soups

- Chicken nuggets and fish sticks

- Frozen dinners and pizza

- Confectionery (candy) and ice cream

- Meal replacement shakes and “protein” bars

Section 2: The Alarming Parallel – The Rise of UPFs and Type 2 Diabetes

The correlation is stark and undeniable. Over the past 50 years, as the food industry perfected the science of ultra-processing, its products have come to dominate the US food supply. A landmark study published in JAMA tracked dietary patterns of American adults and found that ultra-processed food consumption grew from 53.5% of calories in 2001-2002 to 57% by 2017-2018. In some demographic groups, like adolescents and non-Hispanic Black individuals, this figure soared to over 65% of total caloric intake.

This timeline runs in near-perfect parallel with the skyrocketing rates of type 2 diabetes. In 1958, about 1.6 million Americans had diagnosed diabetes. By 2022, that number had exploded to over 38 million. The CDC projects that if current trends continue, 1 in 3 Americans will have diabetes by 2050.

Correlation does not equal causation, but a growing body of rigorous scientific evidence confirms the link. The most compelling evidence comes from a randomized controlled trial published in the journal Cell Metabolism. In this study, 20 healthy, weight-stable adults were admitted to a clinical facility and randomly assigned to eat either an ultra-processed diet or an unprocessed diet for two weeks, immediately followed by the alternate diet for another two weeks. The meals were matched for presented calories, sugar, fat, fiber, and macronutrients.

The results were staggering. On the ultra-processed diet, participants consumed ~500 more calories per day and gained an average of 2 pounds. On the unprocessed diet, they consumed fewer calories and lost weight. This study provided direct, causal evidence that UPFs drive overeating and weight gain—a primary risk factor for type 2 diabetes. But the damage goes far beyond just calories.

Section 3: The Metabolic Sabotage – How UPFs Drive Insulin Resistance

The path from a UPF-heavy diet to a type 2 diabetes diagnosis is not a single road but a multi-lane highway of metabolic disruption. Here’s how these foods systematically sabotage our biology:

1. The “Carbohydrate Tsunami” and the Insulin Overload

Many UPFs are loaded with rapidly digestible carbohydrates in the form of refined flours, maltodextrin, and added sugars (especially HFCS). These ingredients lack the natural fiber matrix that slows down digestion in whole foods like fruit or oats.

- Mechanism: When you eat a UPF like a donut or a sugary cereal, these simple carbs are broken down into glucose almost instantly in your gut, causing a massive, rapid spike in blood sugar.

- Consequence: Your pancreas is forced to respond with an equally massive surge of insulin to shuttle that glucose into cells. Over time, this constant “whiplashing” of high blood sugar and high insulin exhausts the insulin-producing beta cells in the pancreas. Simultaneously, the body’s cells, bombarded with constant high insulin, become insulin resistant—they stop responding to the hormone’s signal. This is the fundamental defect in type 2 diabetes.

2. The Fattening of the Liver (Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease – NAFLD)

High-fructose corn syrup, a ubiquitous sweetener in UPFs, is particularly nefarious. Unlike glucose, which is metabolized by all cells in the body, fructose is almost exclusively processed in the liver.

- Mechanism: In large, concentrated doses (as found in sodas and sweetened snacks), fructose overwhelms the liver’s capacity to process it for energy. Instead, the liver converts it into fat through a process called de novo lipogenesis (new fat creation).

- Consequence: This leads to a buildup of fat in the liver, known as NAFLD. A fatty liver is highly inflamed and insulin resistant itself, further contributing to the overall insulin resistance in the body and accelerating the path to diabetes.

3. The Gut Microbiome Assault

Our gut is home to trillions of bacteria, collectively known as the gut microbiome, which plays a crucial role in metabolism, immunity, and even hormone regulation. A healthy gut microbiome is diverse and rich in fiber-fermenting bacteria.

- Mechanism: UPFs are typically low in the prebiotic fiber that our good gut bacteria thrive on. Furthermore, common additives in UPFs, such as emulsifiers (e.g., polysorbate-80, carboxymethylcellulose), have been shown in animal studies to damage the protective mucus layer of the gut and directly cause gut inflammation and dysbiosis (an imbalance in gut bacteria).

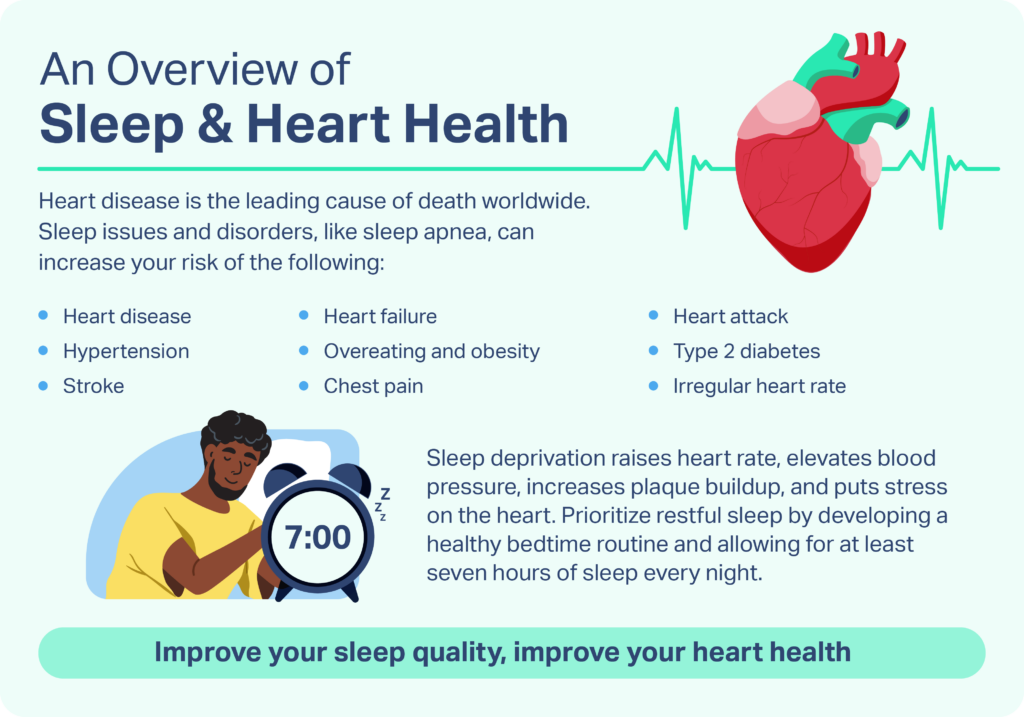

- Consequence: Dysbiosis and a “leaky gut” (increased intestinal permeability) can trigger chronic, low-grade systemic inflammation. This inflammation is a key driver of insulin resistance in muscle and fat tissue.

Read more: Heartburn & GERD: When to See a Doctor and What to Ask About Acid Reflux

4. The “Food Matrix” Destruction and Satiety Failure

Whole foods have a complex, natural structure—the “food matrix”—that dictates how we digest them and how full they make us feel. An almond, for example, has its fats and calories locked within cell walls that require work to break down.

- Mechanism: Ultra-processing violently dismantles this natural food matrix. The fats, carbs, and proteins are broken down and recombined into soft, easily digested formulations.

- Consequence: This leads to two problems: 1) Faster calorie absorption, contributing to blood sugar spikes, and 2) Blunted satiety signals. Your brain doesn’t register the calories from a fruit smoothie or a bag of chips the same way it does from chewing whole fruit and nuts. This is a major reason why people overconsume calories on a UPF diet without realizing it.

Section 4: Beyond the Plate – The Vicious Cycle of an Obesogenic Environment

The choice to eat UPFs is often not a simple lack of willpower. It is a predictable response to a “toxic food environment” engineered by powerful economic and societal forces.

- Economic Access and Food Deserts: Real, whole food is often more expensive and less accessible than UPFs. In many low-income urban and rural areas (“food deserts”), convenience stores stocked with UPFs are the primary food source, while supermarkets with fresh produce are miles away.

- Aggressive Marketing: The food industry spends billions annually marketing UPFs, particularly to children, creating lifelong brand loyalties and taste preferences for hyper-palatable foods.

- Convenience and Time Scarcity: For time-poor families, the convenience of a ready-made, shelf-stable, quickly prepared UPF meal is an understandable choice over the labor and time required for cooking from scratch.

This environment creates a vicious cycle: stress and lack of time lead to UPF consumption, which drives metabolic dysfunction, low energy, and further poor food choices, deepening the public health crisis.

Section 5: Reclaiming Our Health – A Practical Guide to Shifting Away from UPFs

The good news is that insulin resistance and even early-stage type 2 diabetes can often be reversed through dietary and lifestyle changes. The goal is not perfection but a consistent shift away from UPFs and toward whole foods.

1. The “Spot and Swap” Strategy:

You don’t need to overhaul your diet overnight. Start by identifying the top one or two UPFs in your daily routine and find a whole-food alternative.

- INSTEAD OF: Sugary breakfast cereal

- TRY: Plain oatmeal with berries and nuts, or eggs with whole-grain toast.

- INSTEAD OF: Chicken nuggets or frozen pizza

- TRY: A simple stir-fry with chicken breast, frozen vegetables, and brown rice, or a homemade pizza on a whole-wheat crust.

- INSTEAD OF: Soda or sweetened juice

- TRY: Sparkling water with a squeeze of fresh lemon or lime, or unsweetened herbal tea.

- INSTEAD OF: Packaged cookies or granola bars

- TRY: An apple with peanut butter, a handful of nuts and dried fruit (no added sugar), or homemade energy balls.

2. Become a Label Detective:

If you must buy packaged food, read the ingredients list.

- Short List Rule: Choose products with a short list of ingredients you recognize as real food.

- Red Flag Ingredients: Be wary of products containing high-fructose corn syrup, hydrogenated oils, maltodextrin, and a long list of artificial flavors, colors, and emulsifiers.

3. Re-learn the Art of Home Cooking:

This is the single most powerful step. Cooking doesn’t have to be complex. Start with simple recipes—a soup, a salad, a sheet-pan dinner with roasted vegetables and protein. Batch cooking on weekends can ensure you have healthy, convenient options during the week.

4. Prioritize Protein and Fiber:

Meals built around a lean protein source (chicken, fish, beans, lentils, tofu) and high-fiber vegetables (broccoli, leafy greens, bell peppers) are inherently more satiating and have a minimal impact on blood sugar, helping to crowd out UPF cravings.

A Final Word of Hope

The American diet dilemma is a formidable challenge, but it is not insurmountable. By understanding the science of how ultra-processed foods hijack our metabolism, we can begin to dismantle their power over our health. Each meal is an opportunity to vote with your fork—for your own well-being and for a future where the type 2 diabetes epidemic is a chapter in our history books, not our destiny. The path forward is a return to real, whole food, one conscious choice at a time.

Read more: The Gut-Brain Connection: How Stress and Anxiety Are Wrecking Your Digestion

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q1: Are all processed foods bad?

No. This is a critical distinction. Minimally processed foods like canned beans, frozen vegetables, plain yogurt, and whole-grain pasta are convenient, affordable, and nutritious staples. The problem lies specifically with ultra-processed foods, which are formulations of industrial ingredients designed to replace whole foods.

Q2: I have a sweet tooth. What are the best alternatives to sugary UPFs?

Satisfy your craving with whole fruits, which contain natural sugar along with fiber, water, and micronutrients that slow its absorption. Options like dates, frozen grapes, or a bowl of berries can be very satisfying. For baking, try using mashed banana or unsweetened applesauce. A small square of dark chocolate (70% cocoa or higher) is also a good option.

Q3: Is it more expensive to eat a whole-foods diet?

It can be perceived as more expensive, but there are strategic ways to make it affordable.

- Prioritize: Spend on whole foods first.

- Buy in Bulk: Items like oats, brown rice, lentils, and frozen vegetables are very cost-effective.

- Cook at Home: This is almost always cheaper than buying ready-made meals or eating out.

- Seasonal and Local: Purchase fruits and vegetables that are in season for better prices and flavor.

- Plan and Reduce Waste: Meal planning helps you buy only what you need, reducing food waste and saving money.

Q4: I’ve heard that “a calorie is a calorie.” Does the source really matter for diabetes risk?

The “calorie is a calorie” model is outdated, especially in the context of metabolic health. 100 calories from a sugary soda and 100 calories from broccoli have vastly different effects on your body. The soda causes a rapid blood sugar spike, inflammation, and fat storage in the liver, while the broccoli provides fiber, vitamins, and a stable blood sugar response. The source of the calorie fundamentally changes how your hormones, metabolism, and gut bacteria respond.

Q5: Can you reverse type 2 diabetes by cutting out ultra-processed foods?

For many individuals, especially in the early stages, adopting a whole-food, low-sugar, and high-fiber diet can lead to dramatic improvements. This can result in significant weight loss, restored insulin sensitivity, and normalized blood sugar levels, potentially allowing people to reduce or eliminate their need for medication under the strict supervision of their healthcare provider. It is often described as putting the disease into “remission.” It is a powerful and effective strategy, but any changes to medication should only be made in consultation with a doctor.