For decades, syphilis was a public health success story in the making. With the discovery of penicillin in the 1940s, this ancient scourge, which had plagued humanity for centuries, became easily curable with a simple, inexpensive course of antibiotics. By the year 2000, rates of syphilis in the United States were at an all-time low, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) launched a national plan to eliminate the disease entirely.

Today, that success story has unraveled into a full-blown and worsening public health crisis. Syphilis, along with its most devastating form, congenital syphilis, has not only returned but is surging at an alarming rate, reaching levels not seen since the 1950s. This is not a failure of medicine—we still have the cure—but a complex failure of our public health systems, social safety nets, and healthcare accessibility. This silent epidemic is a stark indicator of deep-seated inequities and systemic gaps that demand our immediate attention.

Understanding the Pathogen: What is Syphilis?

Syphilis is a sexually transmitted infection (STI) caused by the bacterium Treponema pallidum. It is often called “The Great Imitator” because its signs and symptoms can be easily mistaken for those of many other diseases. The infection progresses through distinct stages, each with its own characteristics:

1. Primary Syphilis

The first sign is typically a single or multiple sore called a chancre (pronounced SHANG-ker) at the location where the bacteria entered the body. The chancre is usually firm, round, and painless, and it appears about 3 weeks after exposure (though this can range from 10 to 90 days). Because it is painless and can be hidden inside the vagina, rectum, or mouth, it often goes unnoticed. The chancre heals on its own within 3 to 6 weeks, regardless of whether a person receives treatment. However, the infection progresses to the secondary stage if left untreated.

2. Secondary Syphilis

This stage is characterized by a skin rash that may appear as rough, red, or reddish-brown spots on the palms of the hands and the soles of the feet. However, the rash can look different on other parts of the body and sometimes be so faint it is missed. Other symptoms may include:

- Fever

- Swollen lymph nodes

- Sore throat

- Patchy hair loss

- Headaches and body aches

- Fatigue

- Weight loss

Like the primary stage, these symptoms will resolve without treatment, but the infection progresses to the latent and potentially tertiary stages.

3. Latent and Tertiary Syphilis

The latent stage is a period where there are no visible signs or symptoms. The bacteria remain in the body, and the infection can only be detected by a blood test. This stage can last for years.

Tertiary syphilis is the final, most destructive stage, occurring 10-30 years after the initial infection. It can damage the brain, nerves, eyes, heart, blood vessels, liver, bones, and joints. This damage can be severe enough to cause paralysis, blindness, dementia, and even death. Fortunately, due to antibiotic treatment, tertiary syphilis is rare today.

The Most Devastating Outcome: Congenital Syphilis

Congenital syphilis occurs when a pregnant person with syphilis passes the infection to their baby during pregnancy. The consequences for the infant are often catastrophic.

- Transmission: The bacterium can cross the placenta at any time during pregnancy, but the risk of transmission is highest during the primary and secondary stages of the mother’s infection. Without treatment, there is up to an 80% chance of an adverse outcome for the pregnancy.

- Consequences for the Baby: The effects can be devastating and include:

- Miscarriage (fetal death before 20 weeks)

- Stillbirth (fetal death after 20 weeks)

- Neonatal death (death within the first 28 days of life)

- Low birth weight

- Premature birth

- Developmental delays

- Seizures

- A host of physical manifestations at birth, including rashes, bone abnormalities, severe anemia, an enlarged liver and spleen, jaundice, and brain and nerve problems, such as blindness or deafness.

The most profound tragedy of congenital syphilis is that it is almost 100% preventable. With timely testing and adequate treatment of the pregnant person, the infection in the baby can be prevented, and an infected newborn can be cured.

The Data: A Crisis in Plain Sight

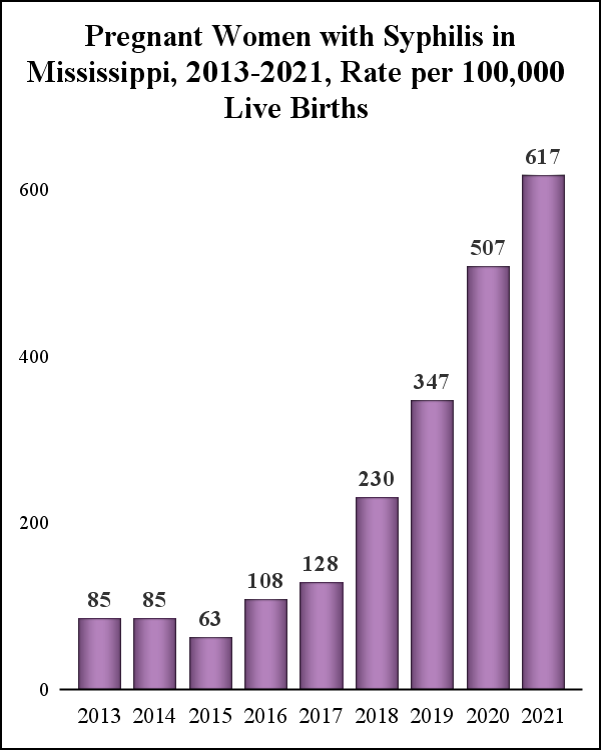

The statistics paint a grim picture of a crisis that has been building for years.

- Overall Syphilis: In 2022, the U.S. saw more than 207,000 reported cases of all stages of syphilis, the highest number since 1950. This represents an 80% increase since 2018.

- Congenital Syphilis: The numbers are even more staggering. Reported cases of congenital syphilis skyrocketed from 335 in 2012 to 3,761 in 2022—a more than tenfold increase in a single decade. These cases were linked to 282 stillbirths and infant deaths in 2022 alone.

- Disparities: The epidemic does not affect all populations equally. It disproportionately impacts:

- Racial and Ethnic Minorities: In 2022, the rate of primary and secondary syphilis among Black Americans was 4.7 times the rate among White Americans. American Indian/Alaska Native people had a rate 6.7 times higher, and Hispanic/Latino people had a rate 2.4 times higher. These disparities are even more pronounced for congenital syphilis.

- Geographic Regions: Cases are concentrated in the South and West, with states like Texas, California, Arizona, and Louisiana reporting some of the highest numbers.

- Gender and Sexual Orientation: While the resurgence initially affected men who have sex with men (MSM), the epidemic has increasingly spread to heterosexual men and women, which is the primary driver behind the rise in congenital syphilis.

Root Causes: Why is This Happening Now?

The resurgence of syphilis is not due to a single cause but a perfect storm of interconnected systemic, social, and economic failures.

1. Erosion of Public Health Infrastructure

The success in driving syphilis to near-elimination led to complacency and a shift in funding and focus. Many local and state health departments that once had robust STI prevention and control programs saw their budgets slashed. This resulted in the closure of dedicated STI clinics, reduced hours, and layoffs of experienced disease intervention specialists (DIS). These specialists are the detectives of public health; they conduct contact tracing, notify partners, and ensure infected individuals get treatment. Without this frontline workforce, chains of transmission go unbroken.

2. Socioeconomic Determinants of Health

Syphilis thrives where poverty, homelessness, and lack of access to care are prevalent.

- Poverty and Homelessness: Individuals experiencing homelessness or unstable housing face immense barriers to healthcare, including lack of transportation, insurance, and the ability to store medications or attend follow-up appointments.

- Substance Use: The ongoing opioid and methamphetamine epidemics are significant drivers. Substance use can impair judgment, leading to higher-risk sexual behaviors. Furthermore, it often destabilizes lives, making healthcare a lower priority.

- Mass Incarceration: Jails and prisons are hotspots for STI transmission, and individuals released back into their communities often lack continuity of care.

3. Healthcare Access Barriers

The U.S. healthcare system is notoriously fragmented and difficult to navigate for many.

- Lack of Insurance: Uninsured individuals are less likely to seek routine care, including STI testing.

- Stigma and Discrimination: The stigma surrounding STIs, sexuality, and substance use can prevent people from seeking testing and treatment. For marginalized communities, including people of color and LGBTQ+ individuals, historical and ongoing discrimination within the healthcare system fosters distrust and acts as a powerful deterrent to care.

- Rural Health Deserts: Many rural areas have seen a closure of hospitals and clinics, creating “maternity care deserts” where pregnant people have no local access to obstetric care or STI testing.

4. The Prenatal Care Gap

Every case of congenital syphilis represents a failure in the prenatal care system. The CDC estimates that nearly 9 out of 10 cases in 2022 could have been prevented with timely testing and treatment during pregnancy.

- Late or No Prenatal Care: A significant number of cases occur in people who did not receive timely prenatal care. The reasons are multifaceted, including the barriers mentioned above.

- Inadequate Management: Shockingly, about 40% of cases occur in people who did receive some prenatal care but were not adequately tested or treated. This points to failures in the standard of care, such as:

- Testing only once in the first trimester and missing an infection acquired later in pregnancy.

- Failing to test at the time of delivery.

- Diagnosing syphilis but failing to ensure the patient completes the full treatment, which often requires multiple penicillin injections.

5. Supply Chain Issues

A critical, and often overlooked, factor is the ongoing shortage of Bicillin L-A (benzathine penicillin G), the only recommended treatment for syphilis in pregnant people and the most effective treatment for late-stage syphilis. This shortage, driven by manufacturing issues and increased demand, has made it incredibly difficult for clinics and health departments to secure the medication, leading to treatment delays and potentially contributing to adverse outcomes.

Read more: The Cost of Caring: Navigating the US Healthcare System for Mental Wellness

A Path Forward: Multifaceted Solutions for a Complex Problem

Reversing this tide requires a coordinated, well-funded, and compassionate national strategy that addresses the problem at every level.

1. Rebuilding and Modernizing Public Health Infrastructure

- Sustained Funding: Congress and state legislatures must commit to long-term, sustained funding for public health. This includes restoring and expanding the network of STI clinics and rebuilding the workforce of Disease Intervention Specialists.

- Innovative Testing and Outreach: Public health departments must meet people where they are. This includes expanding point-of-care rapid testing in non-traditional settings like emergency departments, syringe service programs, homeless shelters, and prisons. At-home testing kits for syphilis could also be a game-changer in increasing accessibility.

2. Strengthening the Prenatal Safety Net

- Optimizing Testing Protocols: We must implement and enforce CDC-recommended testing for all pregnant people: at the first prenatal visit, again in the third trimester (at 28 weeks), and at delivery. States should consider making third-trimester testing mandatory.

- Addressing Barriers to Prenatal Care: Initiatives like Medicaid expansion, extending postpartum coverage, and providing support services for transportation and childcare can make prenatal care more accessible.

- Provider Education and Accountability: Healthcare providers, particularly obstetricians, family doctors, and midwives, need ongoing education on the current syphilis guidelines, the importance of timely treatment, and the need for a non-judgmental, trauma-informed approach to care.

3. Tackling Social and Structural Drivers

- Housing-First Models: Stable housing is a prerequisite for health. Providing housing for individuals experiencing homelessness can dramatically improve their ability to engage in healthcare.

- Harm Reduction Integration: Syringe service programs are critical points of contact. Integrating STI testing, treatment, and prevention services (like condom distribution and PrEP for HIV) into these programs can effectively reach a high-risk population.

- Culturally Competent and Trustworthy Care: Public health campaigns and clinical services must be developed in partnership with the communities they aim to serve. Training healthcare workers in cultural competency and implicit bias is essential to rebuilding trust.

4. Policy and Advocacy

- Address the Penicillin Shortage: The federal government must work with pharmaceutical manufacturers to resolve the Bicillin L-A shortage as a public health priority.

- Expand Medicaid: The 10 states that have not yet expanded Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act have some of the highest rates of congenital syphilis. Expansion would provide coverage to millions of low-income adults, including those who are pregnant or may become pregnant.

- Comprehensive Sex Education: Evidence-based sex education that includes information on STI prevention, testing, and treatment is a fundamental pillar of public health.

Conclusion: A Preventable Tragedy Demands a Moral Response

The alarming rise of syphilis and congenital syphilis in one of the world’s wealthiest nations is not a medical mystery. It is a symptom of a fractured system. We have the knowledge, the tools, and the cure to end this suffering. What has been lacking is the collective will, funding, and political priority to do so.

Each case of congenital syphilis, each stillbirth, each newborn suffering from a preventable disease, is a mark of failure. Addressing this silent epidemic requires us to look beyond the bacterium itself and confront the underlying inequities in our society. It demands that we rebuild a public health infrastructure that serves everyone, that we ensure equitable access to quality healthcare, and that we treat sexual health with the seriousness and compassion it deserves. The time for action is now. We must not allow this preventable tragedy to define our nation’s health for another decade.

Read more: The Anxious American: A Practical Guide to Managing Anxiety in an Age of Uncertainty

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q1: I’ve been diagnosed with syphilis. Is it curable?

A: Yes, syphilis is completely curable with the right antibiotics, typically a penicillin injection. The type, dose, and number of injections depend on the stage of the infection. It is crucial to complete the full course of treatment as prescribed by your healthcare provider. Follow-up blood tests are often needed to ensure the infection has been cured.

Q2: How can I protect myself from getting syphilis?

A: The most reliable way to avoid STIs is to abstain from sex or to be in a long-term, mutually monogamous relationship with a partner who has been tested and is known to be uninfected. For those who are sexually active, consistent and correct use of latex condoms can reduce the risk of transmission, though condoms are not 100% effective as sores can occur in areas not covered by a condom. Regular STI testing is also essential, especially if you have new or multiple partners.

Q3: How often should I get tested for syphilis?

A: The CDC recommends at least annual testing for syphilis for all sexually active gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (MSM). For individuals with multiple or anonymous partners, more frequent testing (e.g., every 3 to 6 months) is advised. Anyone who has symptoms of syphilis or whose partner has been diagnosed with an STI should be tested immediately. All pregnant people should be tested at their first prenatal visit.

Q4: I’m pregnant and just found out I have syphilis. What does this mean for my baby?

A: It is understandable to be worried, but the most important thing is to get treated immediately. The treatment for syphilis during pregnancy is penicillin, which is safe for the baby and highly effective at curing both you and your unborn child. The sooner you are treated, the lower the risk of passing the infection to your baby. Your healthcare provider will monitor you and your baby closely throughout the pregnancy.

Q5: Why is penicillin the only recommended treatment for pregnant people with syphilis?

A: Penicillin is the only therapy proven to effectively treat the fetus and prevent congenital syphilis. Other antibiotics, like doxycycline, which are used for non-pregnant individuals, are not safe to use during pregnancy and may not cross the placenta effectively to treat the baby.

Q6: I was treated for syphilis in the past. Can I get it again?

A: Yes. Successful treatment for syphilis cures the infection, but it does not protect you from getting it again. You can become re-infected if exposed to the bacteria again. Ongoing safe sex practices and regular testing are important.

Q7: What is being done to address the Bicillin L-A (penicillin) shortage?

A: The CDC and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) are aware of the shortage and are working with the manufacturer, Pfizer, to address it. In the interim, the CDC has issued guidance for healthcare providers on alternative treatment regimens when Bicillin L-A is unavailable, though these are not preferred for pregnancy. This remains a critical issue that requires a swift resolution.

Q8: Where can I get tested for syphilis?

A: Testing is widely available. You can get tested at:

- Your primary care doctor’s office

- Community health centers

- Sexual health or STI clinics (often offering low or no-cost services)

- Planned Parenthood health centers

Many of these locations offer confidential testing. You can use the CDC’s GetTested website to find a testing location near you.