For over two decades, the opioid crisis has carved a devastating path through communities across the globe, particularly in North America. Headlines rightly focus on the staggering number of lives lost to overdose—a tragic tally that now measures in the hundreds of thousands. However, lurking in the shadow of this acute public health emergency is a quieter, more insidious epidemic of infectious diseases, primarily Hepatitis C (HCV) and Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV).

This is not a coincidence but a consequence. The same behaviors that drive opioid addiction, specifically the shift to intravenous (IV) drug use as tolerance builds and costs rise, create the perfect storm for the transmission of bloodborne pathogens. What begins as a quest to alleviate pain or escape reality can quickly spiral into a complex web of health crises, where a single needle can transmit a chronic, life-altering infection alongside the immediate risk of overdose.

This article delves into the intricate and often overlooked intersection of the opioid crisis and outbreaks of HCV and HIV. We will explore the biological and social mechanisms that link them, the populations most affected, the structural barriers to care, and—most importantly—the evidence-based, compassionate solutions that can break this cycle and save lives. Understanding this connection is not merely an academic exercise; it is a critical imperative for public health officials, healthcare providers, policymakers, and society at large.

Section 1: Understanding the Contagion – The Biology of Transmission

To comprehend why IV drug use is such a potent vector for disease, one must first understand the basic science of how these viruses spread.

1.1 The Perfect Vector: The Shared Syringe

Hepatitis C and HIV are both bloodborne viruses. They cannot be transmitted through casual contact, air, or water. They require direct access to the bloodstream. When a person injects drugs, a small amount of their blood is inevitably drawn back into the syringe and needle. If that syringe is then used by another person, even if the needle appears clean, it introduces the previous user’s blood—and any viruses within it—directly into the next person’s circulation.

This risk is exponentially higher with “syringe pooling” or “booting,” where users draw blood into the syringe to mix with the drug, ensuring a more potent effect. This practice heavily contaminates the equipment. HCV is a particularly resilient and highly concentrated virus in the blood, making it significantly more infectious than HIV in this context. It is estimated that HCV can survive in a syringe for up to 63 days, making even discarded needles a potential hazard.

1.2 Beyond the Needle: The Role of Injection Paraphernalia

The syringe itself is only one part of the transmission equation. The “cooker” (the bottle cap or spoon used to dissolve the drug) and the “cotton” (used to filter impurities) are also critical. When multiple people use the same cooker or cotton to prepare their drugs, blood-contaminated solutions can be drawn up into syringes, facilitating transmission. Sharing any part of the injection equipment is a high-risk behavior.

1.3 The Syndemic Nature: A Triple Threat

The concurrent presence of substance use disorder, HCV, and HIV is known as a “syndemic.” This term describes two or more epidemics interacting synergistically, exacerbating the burden of disease and compounding health disparities. The conditions create a vicious cycle:

- Substance Use Disorder leads to increased exposure to HCV/HIV.

- A HCV or HIV diagnosis can lead to depression, anxiety, and stigma, which may fuel further substance use as a coping mechanism.

- Chronic infection weakens the immune system and damages the liver (HCV) or immune cells (HIV), making the body more vulnerable to other infections and complications.

- Managing multiple chronic conditions becomes overwhelmingly complex for both the patient and the healthcare system.

Section 2: The Scale of the Problem – Data and Demographics

The intersection of the opioid crisis and infectious disease is not a theoretical concern; it is quantifiable and its growth is alarming.

2.1 Hepatitis C: The Silent Surge

Hepatitis C has been the most dramatic indicator of the opioid crisis’s infectious disease fallout.

- Rising Incidence: Following years of decline, acute HCV infections in the United States more than tripled from 2010 to 2019, with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) directly attributing this surge to the increase in IV drug use.

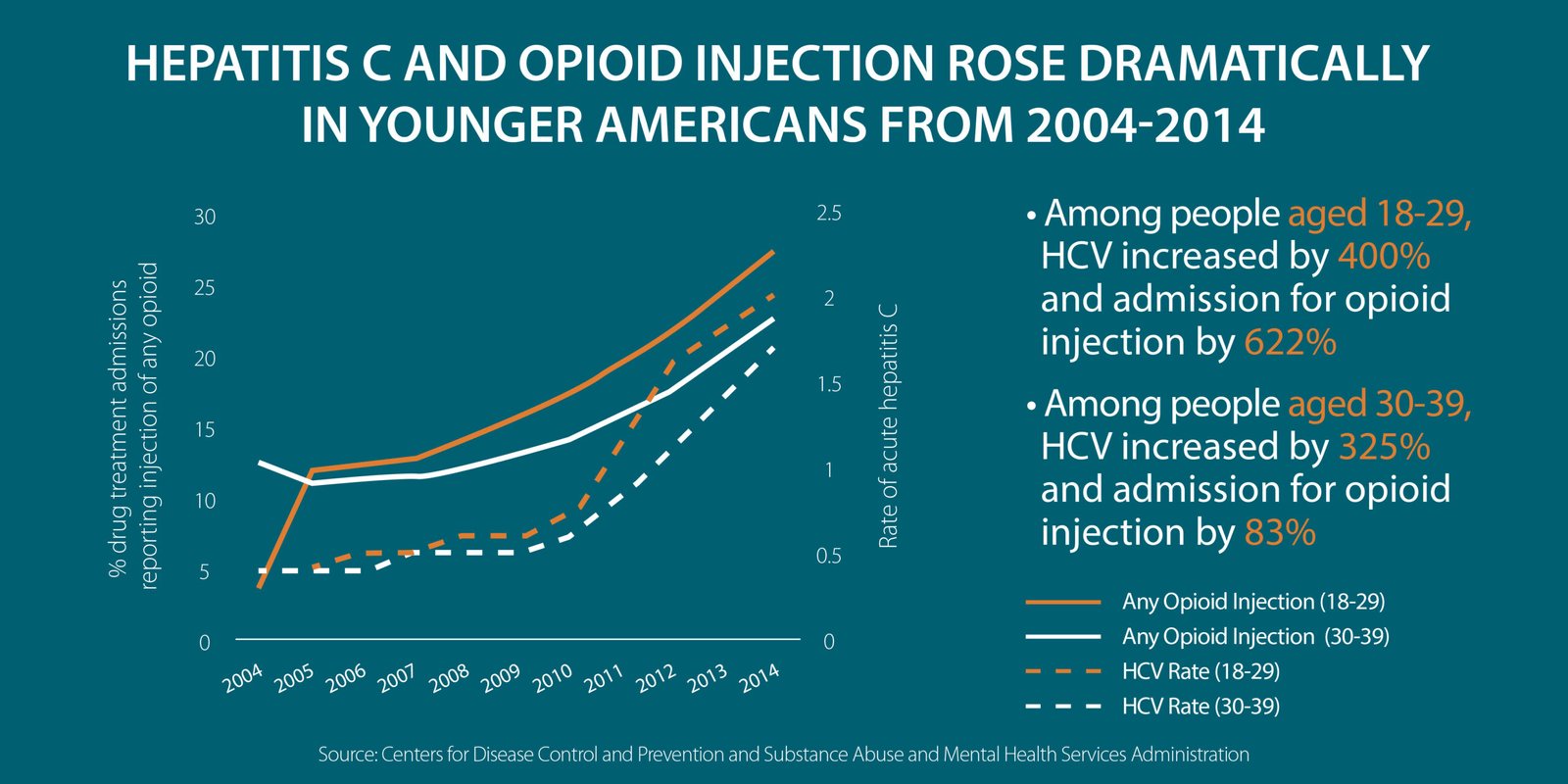

- A Younging Epidemic: Historically, HCV was a disease associated with the “Baby Boomer” generation (born 1945-1965), often infected through blood transfusions before 1992. Today, the fastest-growing cohort of new HCV infections is among young adults (ages 20-39) living in rural and suburban areas—the very demographics hardest hit by the opioid epidemic.

- The Burden of Chronic Disease: An estimated 2.4 million people in the U.S. are living with chronic HCV. If left untreated, HCV can lead to severe liver damage, cirrhosis, liver cancer, and the need for a transplant. The healthcare costs associated with managing these advanced liver diseases are enormous.

2.2 HIV: Concentrated Outbreaks

While the overall rate of HIV diagnoses attributed to IV drug use has decreased in the U.S. due to broad prevention efforts, the opioid crisis has sparked alarming localized outbreaks that serve as warning signs.

- The 2015 outbreak in Scott County, Indiana, is a canonical example. A predominantly rural community with a high prevalence of opioid use disorder (OUD) and no syringe service programs saw 215 new HIV infections traced back to shared injection equipment in a matter of months.

- Similar, though smaller, outbreaks have been identified in other rural communities across Appalachia and the Midwest, demonstrating the vulnerability of regions with underfunded public health infrastructure.

- Globally, the link is even more stark. In Eastern Europe and Central Asia, IV drug use remains a primary driver of HIV transmission.

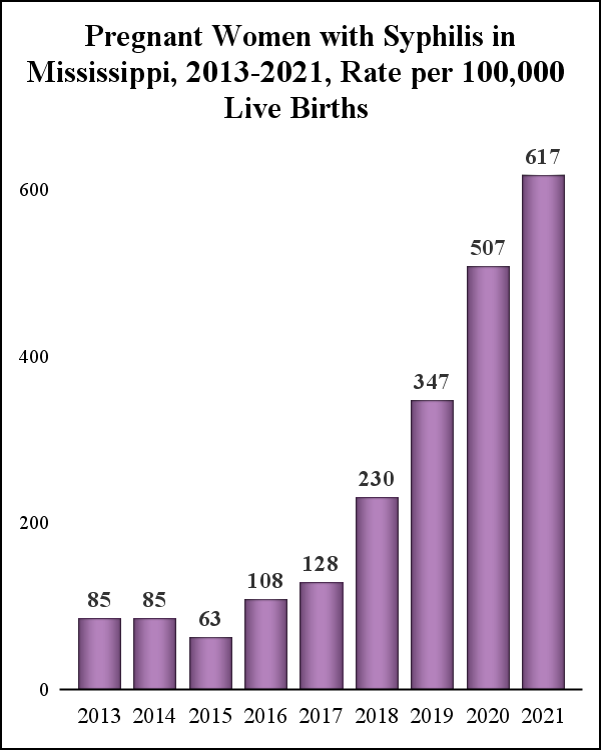

2.3 Shifting Geographies: From Urban Centers to Rural Heartlands

The opioid epidemic has fundamentally altered the geography of infectious disease. Previously, HCV and HIV outbreaks linked to drug use were concentrated in urban centers. Today, they are proliferating in rural and semi-rural areas where:

- Public Health Resources are scarce or non-existent.

- Harm Reduction Services like syringe exchanges are often politically contentious or illegal.

- Stigma is profoundly high, preventing people from seeking help.

- Access to Healthcare is limited, with few specialists treating either addiction or infectious diseases.

Section 3: The Human and Systemic Barriers to Care

The biological mechanism of transmission is straightforward. The reasons why people struggling with addiction cannot or do not access care are heartbreakingly complex.

3.1 Stigma: The Invisible Wall

Stigma is arguably the single greatest barrier to addressing this syndemic.

- Addiction Stigma: The pervasive view of addiction as a moral failing rather than a chronic, treatable medical condition prevents individuals from seeking help for their substance use disorder. They fear judgment from family, friends, employers, and even healthcare providers.

- Disease Stigma: The stigmas associated with HCV and HIV, often wrongly intertwined with judgments about sexuality and lifestyle, create a powerful double burden. A person may be reluctant to get tested for fear of a positive diagnosis and the accompanying shame.

3.2 The Criminalization of Addiction

Policies that criminalize drug possession and paraphernalia directly fuel the spread of disease.

- Fear of Arrest: Laws against possessing syringes without a prescription discourage people from carrying their own sterile equipment, for fear of being arrested. This leads to the reuse and sharing of syringes.

- Prison as a Vector: Incarceration often disrupts treatment and places individuals in environments where drug use continues, but access to sterile syringes is nonexistent, creating high-risk situations for transmission.

3.3 Fragmented Healthcare Systems

The traditional healthcare system is poorly equipped to handle the syndemic nature of this crisis.

- Siloed Care: A patient may see a primary care physician for general health, a psychiatrist for mental health, a separate provider for addiction treatment (if they can find one), and an infectious disease specialist for HCV/HIV. This fragmentation leads to poor communication, missed appointments, and treatment dropout.

- Lack of Integrated Services: It is rare to find a single clinic that offers testing for HCV/HIV, immediate initiation of treatment for these infections, and medication-assisted treatment (MAT) for opioid use disorder all under one roof.

3.4 Financial and Logistical Hurdles

- Cost: While highly effective cures for HCV exist, their high upfront cost can be a barrier for uninsured or underinsured individuals and for state Medicaid programs, which often impose restrictions on who can receive treatment.

- Transportation and Poverty: Rural populations often lack reliable transportation to travel to distant clinics for ongoing treatment. Poverty, which is both a driver and a consequence of addiction, makes it impossible to prioritize healthcare over immediate needs like food and shelter.

Section 4: A Path Forward: Evidence-Based and Compassionate Solutions

Despite the grim statistics, there is a clear and evidence-based roadmap for addressing this syndemic. The solutions are not merely medical; they are social, political, and moral.

4.1 Harm Reduction: A Foundation of Public Health

Harm reduction is a set of practical strategies and ideas aimed at reducing negative consequences associated with drug use. It meets people where they are at, acknowledging that while abstinence is an ideal goal, reducing harm in the meantime saves lives.

- Syringe Service Programs (SSPs): Also known as needle exchanges, SSPs are one of the most thoroughly evaluated and effective public health interventions. They provide sterile syringes, safely dispose of used ones, and offer other supplies like cookers, cotton, and alcohol wipes. Decades of research confirm that SSPs:

- Dramatically reduce the transmission of HCV and HIV.

- Do not increase drug use or crime in the communities they serve.

- Serve as a critical gateway to other services, including overdose prevention, testing, and addiction treatment.

- Naloxone Distribution: Widespread distribution of naloxone, a medication that can reverse an opioid overdose, is a core harm reduction practice. By training people who use drugs and their loved ones to administer naloxone, thousands of lives are saved each year, preserving the opportunity for future recovery.

- Drug Checking Services: These services allow individuals to test their drugs for the presence of potent contaminants like fentanyl or xylazine, enabling them to make informed decisions and reduce their risk of overdose.

4.2 Treatment and Cure: Breaking the Biological Cycle

- Medication-Assisted Treatment (MAT) for OUD: MAT, using FDA-approved medications like buprenorphine, methadone, and naltrexone, is the gold standard for treating opioid use disorder. It stabilizes brain chemistry, reduces illicit opioid use, and saves lives. Crucially, it also reduces injection drug use, thereby directly interrupting the transmission of HCV and HIV. Expanding access to MAT is the single most impactful step in reducing IV drug use.

- Direct-Acting Antivirals (DAAs) for Hepatitis C: The development of DAAs represents a monumental breakthrough. These pills, typically taken for 8-12 weeks, cure over 95% of HCV cases with minimal side effects. Curing HCV not only restores an individual’s health but also eliminates them as a source of transmission, contributing to community-wide elimination efforts.

- HIV Treatment as Prevention: Modern antiretroviral therapy (ART) for HIV is so effective that it can reduce a person’s viral load to an undetectable level. It is now a settled scientific fact that individuals with an undetectable viral load cannot sexually transmit HIV (U=U). While this does not directly apply to blood transmission through shared needles, successful ART dramatically improves health outcomes and reduces the overall community viral load.

4.3 Integrated Care Models: Treating the Whole Person

The most promising approach to this syndemic is the integration of services.

- “One-Stop-Shop” Clinics: Models that co-locate addiction treatment (MAT), infectious disease care (HCV/HIV testing and treatment), mental health services, and primary care have shown remarkable success. A person can see their addiction counselor, get their MAT prescription, and have their HCV managed in a single, stigma-free visit.

- Low-Barrier MAT: Removing hurdles like mandatory counseling, excessive paperwork, and frequent required visits makes treatment more accessible for the most vulnerable populations.

- Telehealth and Mobile Health Units: These innovations are particularly effective in rural areas, bringing testing, counseling, and prescription services directly to communities in need.

4.4 Policy and Education: Creating an Enabling Environment

- Decriminalization and Public Health Laws: Shifting the response from punishment to public health is crucial. This includes repealing laws that criminalize syringe possession and expanding Good Samaritan laws that protect people who call for help during an overdose.

- Medicaid Expansion and Reform: Expanding Medicaid in all states is critical, as it is a primary payer for addiction and infectious disease treatment for low-income individuals. Furthermore, states must be encouraged to remove prior authorization and sobriety restrictions for HCV treatment.

- Comprehensive Sex Education: Honest, evidence-based education in schools that includes information about substance use and bloodborne pathogens can equip young people with knowledge to protect themselves.

Conclusion: A Call for Compassion and Coherent Policy

The intertwined epidemics of opioid use disorder, Hepatitis C, and HIV represent one of the most complex public health challenges of our time. They are a stark reminder that health crises do not exist in isolation; they feed on and exacerbate one another, preying on the most vulnerable among us.

To combat this syndemic, we must move beyond stigma and punishment and embrace a public health approach rooted in evidence, compassion, and pragmatism. The tools exist: harm reduction saves lives in the present, and modern medical treatments offer cure and recovery for the future. The path forward requires the integration of these services, the dismantling of systemic barriers, and a steadfast commitment to viewing addiction not as a crime, but as a treatable medical condition.

By shining a light on the infectious shadow of the opioid crisis, we can begin to develop a coherent, humane, and effective response that honors the dignity of every individual and heals our communities from the inside out. The goal is not just to end an epidemic, but to rebuild a system of care that leaves no one behind.

Read more: Navigating the Maze: How to Find the Right Therapist and Understand Your Insurance in the US

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q1: I don’t use drugs, and no one in my family does. Why should I care about funding syringe exchanges or addiction treatment?

This is a common and understandable question. The response is multi-faceted:

- Public Health and Economics: Untreated HCV and HIV are incredibly expensive for the healthcare system. A liver transplant for end-stage HCV can cost over $800,000. Lifelong HIV medication is also very costly. Preventing these infections through cost-effective measures like SSPs saves taxpayer money in the long run.

- Community Safety: SSPs safely collect and dispose of used syringes, reducing the number of needles found in parks and public spaces, which protects children and first responders.

- Compassion: Addiction is a disease that can affect anyone, regardless of background. A compassionate society invests in solutions that help its members recover and lead healthy, productive lives.

Q2: Don’t syringe programs enable and encourage drug use?

This is a persistent myth, but it is not supported by evidence. Numerous studies conducted by the CDC, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, and the World Health Organization have conclusively shown that SSPs do not increase the rate of drug use. In fact, they serve as a critical contact point to engage people in health services and addiction treatment. They are a bridge to recovery, not a roadblock.

Q3: What’s the point of treating Hepatitis C in someone who is still using drugs? Won’t they just get re-infected?

This is a crucial point that reflects an outdated mindset.

- First, curing HCV is a medical good in itself. It prevents liver failure, cancer, and death.

- Second, it is a prevention strategy. Once cured, that person can no longer transmit the virus to others, helping to stop the outbreak at its source.

- Third, the fear of re-infection should not deny someone care. Successfully treating a person’s HCV can be a powerful, positive experience that builds trust in the healthcare system and can motivate them to seek treatment for their substance use disorder. The cure rate with DAAs is so high that even if re-infection occurs, the person can be treated again.

Q4: How infectious are HCV and HIV from a needle stick injury, say for a first responder or a citizen who finds a discarded needle?

The risk depends on the virus and the situation.

- Hepatitis C: The risk of infection from a needlestick exposure involving an HCV-positive source is approximately 1.8% (about 1 in 50).

- HIV: The risk for HIV transmission from a percutaneous (through the skin) needlestick is significantly lower, about 0.23% (roughly 1 in 435).

It’s important for anyone who experiences a needlestick injury to seek immediate medical attention for post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP), which can prevent HIV infection if started promptly.

Q5: What can I do if I’m worried about a loved one who is injecting drugs?

This is an incredibly difficult and painful situation.

- Educate Yourself: Understand that addiction is a complex brain disorder, not a choice.

- Communicate with Compassion: Express your concern without judgment. Use “I” statements, such as “I am worried about you and I care about your health.”

- Have Naloxone On Hand: Learn how to use it. You could save their life.

- Provide Harm Reduction Resources: Offer information about local syringe service programs or where to get sterile equipment. This is about keeping them alive until they are ready for treatment.

- Gently Offer Treatment Options: When the moment feels right, provide information about Medication-Assisted Treatment (MAT) and offer to help them make an appointment. The SAMHSA National Helpline (1-800-662-4357) is a free, confidential resource for finding treatment.

- Take Care of Yourself: Seek support for yourself through groups like Al-Anon or Nar-Anon, which provide support for friends and family of people with addiction.