In 2000, the United States declared a monumental public health victory: measles was eliminated. This declaration did not mean the disease was gone forever, but that it was no longer constantly present within the country. Thanks to the highly effective and widely adopted Measles, Mumps, and Rubella (MMR) vaccine, the once-common specter of measles—a disease that hospitalized tens of thousands and killed hundreds of American children annually in the pre-vaccine era—had been banished.

Today, that ghost is back, rattling its chains in our communities. From a large outbreak at a Florida elementary school to clusters of cases in Chicago, Philadelphia, and Ohio, measles is making a troubling comeback. The common thread weaving through these outbreaks is not a mysterious new strain or a failure of the vaccine, but a human-made crisis: vaccine hesitancy.

This article will explore the intricate and alarming phenomenon of how the deliberate delay or refusal of vaccines, despite their availability, is dismantling our herd immunity and opening the door for a dangerous, preventable disease to return. We will dissect the roots of vaccine hesitancy, analyze its tangible impact on public health, and outline the collective action required to protect our most vulnerable. The return of measles is a story of scientific triumph undermined by misinformation, and it is a story we have the power to rewrite.

Part 1: Understanding Measles – Not Just a Little Rash

To fully grasp the gravity of its return, one must understand the true nature of the measles virus. Public perception, shaped by its absence, has often minimized it as a benign childhood illness involving a few days of fever and a spotty rash. This characterization is dangerously inaccurate.

What is the Measles Virus?

Measles is caused by a paramyxovirus, one of the most contagious pathogens known to humans. It is so infectious that if one person has it, up to 90% of the non-immune people close to that person will also become infected. The virus resides in the nose and throat of an infected person and can live for up to two hours in the airspace or on surfaces after that person has left the room. Transmission occurs through coughing, sneezing, or even just breathing.

The Clinical Course: A Systemic Assault

The infection unfolds in distinct stages over two to three weeks:

- Incubation: For 10-14 days after exposure, there are no symptoms. The virus is silently replicating.

- Prodrome (Non-specific symptoms): This phase lasts 2-4 days and is characterized by:

- High fever (often spiking to 104°F or 40°C)

- Malaise, irritability

- The “three C’s”: Cough, Coryza (runny nose), and Conjunctivitis (red, watery eyes).

- Koplik’s spots: Tiny white spots with bluish-white centers on a red background found inside the mouth on the inner lining of the cheek. These are a definitive sign of measles, often appearing before the classic rash.

- The Rash: The characteristic red, blotchy rash typically begins on the face and hairline before spreading down the body. As it spreads, the fever may spike again. The rash is a visible sign of the body’s immune response to the virus circulating in the bloodstream.

- Recovery: The rash and fever usually subside after a few days, and the person begins to recover. However, the danger is far from over.

The Real Danger: Devastating Complications

It is the complications of measles that make it a formidable threat, especially to children under 5 and adults over 20. Approximately 1 in 5 unvaccinated people in the U.S. who get measles will be hospitalized.

Common and severe complications include:

- Diarrhea and Otitis Media (Ear Infections): Common but can lead to permanent hearing loss.

- Pneumonia: The leading cause of measles-related deaths in young children. It occurs in about 1 in 20 children with measles.

- Acute Encephalitis: A dangerous inflammation of the brain that occurs in about 1 in 1,000 cases. It can lead to convulsions, deafness, and permanent intellectual disability.

- Long-Term Terror: Subacute Sclerosing Panencephalitis (SSPE): This is a rare but invariably fatal neurological disorder caused by a persistent infection with a defective measles virus. It typically develops 7 to 10 years after a person has recovered from measles, even if the initial case was mild. It causes progressive cognitive and motor decline, leading to a vegetative state and death. The risk is highest for children who contract measles before the age of 2.

The Pre-Vaccine Era: A Necessary Reminder

Before the measles vaccine was introduced in 1963, the U.S. saw:

- An estimated 3-4 million cases each year.

- 48,000 hospitalizations annually.

- 400-500 deaths annually.

- 1,000 cases of chronic disability from encephalitis each year.

This is the suffering that the MMR vaccine prevented. This is the past we risk revisiting.

Part 2: The Triumph of Science – The MMR Vaccine

The development of the measles vaccine stands as one of the greatest public health achievements of the 20th century.

A Brief History

The first measles vaccines were licensed in 1963. John F. Enders and his team, who had previously won a Nobel Prize for culturing the polio virus, successfully isolated and weakened the measles virus, creating the Edmonston-Enders strain that forms the basis for all measles vaccines used today. The combined MMR vaccine, which protects against measles, mumps, and rubella in a single shot, was introduced in 1971, simplifying the childhood immunization schedule.

Efficacy and Schedule

The MMR vaccine is remarkably effective. One dose is about 93% effective at preventing measles; two doses are about 97% effective. The CDC recommends the following schedule:

- First dose: 12-15 months of age

- Second dose: 4-6 years of age

The two-dose schedule ensures that the small percentage of children who do not develop immunity after the first dose (about 7%) get a second chance at full protection.

Safety and the Debunking of a Fraud

The MMR vaccine has an excellent safety record. Common side effects are mild and temporary, including soreness at the injection site, fever, and a mild rash. Serious allergic reactions are extremely rare.

No discussion of the MMR vaccine is complete without addressing the source of much modern hesitancy: the 1998 study by Andrew Wakefield published in The Lancet. The study, which suggested a link between the MMR vaccine and autism, was later revealed to be an “elaborate fraud.” Investigations found that Wakefield had manipulated data, violated ethical protocols, and had undisclosed major financial conflicts of interest. The Lancet fully retracted the paper in 2010, and Wakefield was struck from the UK medical register.

Since then, dozens of large-scale, robust epidemiological studies involving millions of children across the globe have conclusively found no link between the MMR vaccine and autism. The scientific consensus on this is as solid as the consensus on climate change or the link between smoking and lung cancer.

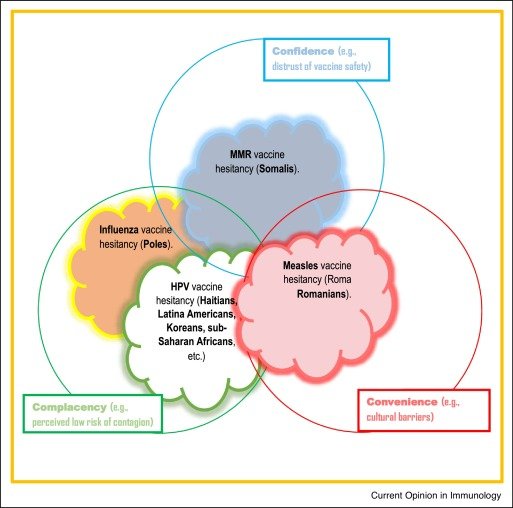

Part 3: The Anatomy of Vaccine Hesitancy – Why Parents Hesitate

Vaccine hesitancy is not a monolithic movement but a complex, nuanced spectrum of beliefs and concerns. Understanding its drivers is key to addressing it.

1. The Misinformation Ecosystem

The internet and social media have become powerful vectors for anti-vaccine misinformation.

- Algorithms and Echo Chambers: Social media algorithms are designed to show users content they engage with, creating “echo chambers” where skeptical parents are fed a continuous stream of anti-vaccine content, reinforcing their fears and isolating them from scientific consensus.

- Anecdotes Over Data: Emotional, personal stories of children who allegedly developed autism or other conditions after vaccination are far more compelling to the human brain than dry, statistical data from large studies. These anecdotes are weaponized, despite the fact that correlation (two things happening around the same time) does not equal causation.

- Distrust of “Big Pharma”: Legitimate concerns about the profit-driven nature of the pharmaceutical industry are leveraged to cast doubt on all medical products, including vaccines. The fact that vaccine safety is monitored by independent government agencies (like the CDC and FDA) and academic researchers worldwide is often ignored.

2. The Paradox of Success

The very success of vaccines is a double-edged sword. Most of today’s parents have never seen a case of measles, polio, or diphtheria. They do not fear the diseases because they have been protected from them. Consequently, the perceived risk of the vaccine (based on misinformation about side effects) begins to loom larger in their minds than the forgotten risk of the disease itself. This is a fundamental failure of risk perception.

3. The Desire for “Natural” Immunity

Some parents believe that contracting the “wild” virus provides superior, more “natural” immunity compared to vaccination. While it is true that natural infection generally confers lifelong immunity, this argument ignores the severe risks of the natural infection pathway. Choosing natural immunity is like choosing to learn to drive by crashing a car instead of taking driver’s ed—the potential consequences are unacceptably high.

4. Concerns about “Overloading” the Immune System

With the modern childhood immunization schedule, children receive several vaccines in their first two years. Some parents worry this “overloads” a child’s immature immune system. This is a biological impossibility. From the moment they are born, infants’ immune systems are battling thousands of antigens (the parts of germs that trigger an immune response) from the bacteria, viruses, and fungi in their environment every day. The entire childhood vaccine schedule contains just a few hundred antigens, a tiny, manageable fraction of what a child’s immune system successfully handles daily.

Part 4: The Consequences of Hesitancy – Erosion of Herd Immunity

When enough parents hesitate, the community-level protection known as herd immunity or community immunity begins to crumble.

What is Herd Immunity?

Herd immunity occurs when a high percentage of a population is immune to a disease, making its spread unlikely. This provides a protective buffer for those who cannot be vaccinated, including:

- Infants too young for the MMR vaccine (under 12 months).

- Individuals with compromised immune systems (e.g., those undergoing chemotherapy, organ transplant recipients, people with HIV).

- People with severe, life-threatening allergies to vaccine components.

Measles is so contagious that it requires a very high threshold for herd immunity: about 95% of a community must be vaccinated to prevent outbreaks.

The Impact of Falling Vaccination Rates

When vaccination rates in a school, neighborhood, or community dip below this 95% threshold, the virus finds a foothold. It seeks out the susceptible individuals—the unvaccinated children, the immunocompromised—and sparks an outbreak. Recent outbreaks have been consistently traced to pockets of low vaccination.

Case Study: The 2014-2015 Disneyland Outbreak

This was a watershed moment. A single infected visitor to the Disneyland theme parks in California sparked an outbreak that ultimately infected 147 people across the U.S., Canada, and Mexico. Genetic analysis showed the virus was identical to a strain circulating in the Philippines. The outbreak spread because it found a critical mass of susceptible, unvaccinated individuals. Subsequent analysis published in JAMA Pediatrics estimated that the MMR vaccination rate among the exposed population at the time was as low as 50-86%, far below the 95% needed for herd immunity. This event demonstrated how a local drop in vaccination could have regional and even national consequences.

Case Study: The 2024-2025 Resurgence

The post-COVID-19 era has seen a significant surge in measles cases. The pandemic led to disruptions in routine childhood immunizations, creating a larger cohort of susceptible children. Furthermore, the politicization of public health and intensified mistrust of health authorities during the COVID-19 pandemic spilled over into routine childhood vaccinations. Outbreaks in Florida, where a surgeon general contradicted CDC guidance during an elementary school outbreak, and in other states, clearly illustrate how leadership and public messaging can either contain or fuel a public health crisis.

Read more: Mindful Eating: Can Your Diet Improve Your Mental Health?

Part 5: The Path Forward – Rebuilding Trust and Uptake

Reversing the trend of vaccine hesitancy requires a multi-faceted, empathetic, and persistent approach.

1. The Role of Healthcare Providers

Pediatricians, family doctors, and nurses are the most trusted sources of information for parents about vaccines. Their role is critical.

- Presumptive Language: Instead of asking, “What do you want to do about vaccines?” which opens the door for debate, using presumptive language like, “Well, Matthew is due for his MMR, DTaP, and chickenpox vaccines today,” normalizes vaccination as the default, standard of care.

- Active Listening and Empathy: Dismissing parents’ concerns as “stupid” is counterproductive. Healthcare providers should listen actively, acknowledge the parent’s fear (e.g., “I understand you’re worried about autism, that’s a very common concern”), and then provide clear, evidence-based information to counter the misinformation.

- The “Primary Care Provider” Advantage: A consistent, trusted relationship with a single provider over time is one of the strongest predictors of vaccine acceptance.

2. Public Health and Policy Interventions

- Strengthening School Vaccine Mandates: All 50 states have laws requiring vaccines for students, but 45 allow exemptions for religious reasons and 15 for “personal” or “philosophical” beliefs. These non-medical exemptions create the pockets of vulnerability where outbreaks begin. States that have eliminated non-medical exemptions, like California, New York, Maine, and Connecticut, have seen a corresponding increase in vaccination rates.

- Combating Misinformation Online: This is a monumental challenge. Public health agencies must become more adept at using social media to disseminate accurate, engaging information. Partnerships with tech companies to de-prioritize or label demonstrably false health information are also crucial.

- Public Education Campaigns: Campaigns should focus not just on vaccine safety, but on the very real dangers of the diseases they prevent. Sharing stories of families affected by measles complications can be a powerful tool to recalibrate risk perception.

3. Community and Social Solutions

- Leveraging Community Influencers: Trusted community leaders—religious figures, local business owners, respected parents—can be powerful advocates for vaccination within their own networks.

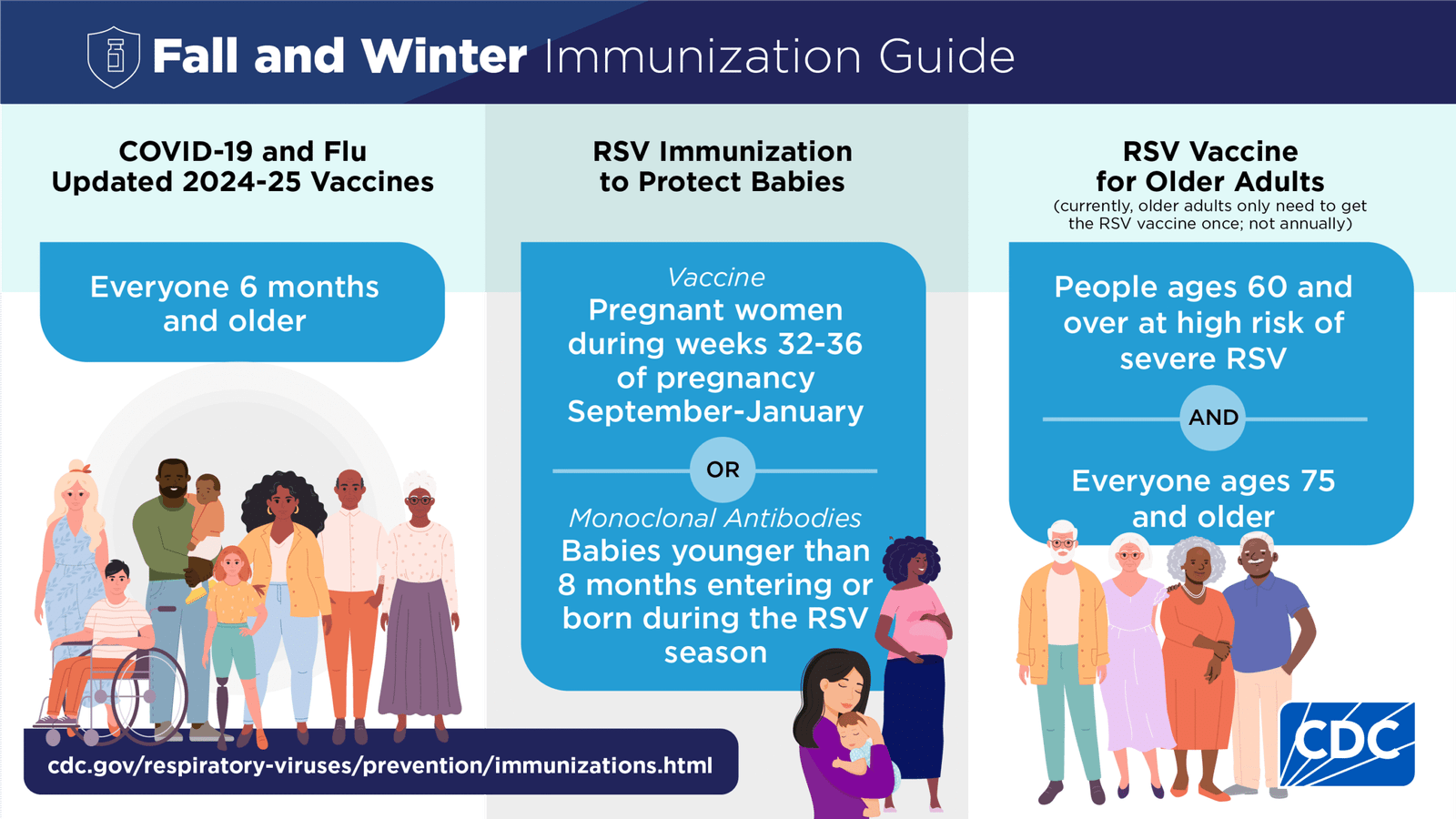

- Improving Access: Removing practical barriers is essential. This includes ensuring vaccines are free or low-cost through programs like Vaccines for Children (VFC), offering vaccination clinics at flexible hours and in convenient locations (e.g., schools, pharmacies, community centers).

Conclusion: A Choice for Our Collective Future

The return of measles is a preventable tragedy. It is a disease we know how to stop, with a tool that is safe, effective, and universally accessible. The outbreaks we are witnessing are not acts of God or inevitable natural phenomena; they are the direct result of choices—choices influenced by a toxic brew of misinformation, eroded trust, and forgotten history.

Protecting our communities from infectious diseases is a collective responsibility. Herd immunity is a social contract. When we vaccinate our children, we are not only protecting them; we are protecting the newborn next door, the elderly grandparent down the street, and the classmate undergoing cancer treatment. We are upholding our duty to our community.

The science is clear. The path is known. The choice between a future free of preventable diseases and a return to a more dangerous past is ours to make. We must choose wisely, for the sake of all our children.

Read more: Can Gut Health Help with Depression & Anxiety? The Science of Psychobiotics

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q1: I heard that the MMR vaccine can cause autism. Is this true?

A: No, this is definitively false. The claim originated from a single, fraudulent 1998 study that has been completely retracted. The lead author was found to have manipulated data and had major undisclosed financial conflicts of interest. Since then, numerous large-scale studies involving millions of children around the world have consistently found no link between the MMR vaccine and autism. The scientific consensus is overwhelming.

Q2: Isn’t it better to get natural immunity from the disease than immunity from a vaccine?

A: While a natural measles infection does provide immunity, it does so at an unacceptably high risk. Choosing natural immunity means rolling the dice on a disease that can cause pneumonia, encephalitis (brain swelling), permanent brain damage, and death. The MMR vaccine provides a safe and effective way to develop immunity without suffering through the dangerous disease and its potential lifelong complications. It’s the difference between practicing with a simulator and crashing a real plane.

Q3: The vaccine schedule seems so aggressive. Isn’t it too much for my baby’s immune system to handle?

A: No. A baby’s immune system is remarkably powerful and is exposed to thousands of germs and antigens every single day from the food they eat, the air they breathe, and the surfaces they touch. The entire childhood vaccine schedule contains only a tiny fraction of the antigens their immune system successfully manages daily. The schedule is meticulously designed by experts to provide protection at the earliest possible moment when children are most vulnerable to these diseases.

Q4: What are the real, common side effects of the MMR vaccine?

A: Most side effects are mild and temporary, a sign that the body is building protection. They include:

- Soreness, redness, or swelling at the injection site.

- A mild fever.

- A temporary, mild rash.

- Swelling of the glands in the cheeks or neck (less common).

These typically occur 7-12 days after the shot and go away on their own. Serious side effects, like a severe allergic reaction, are extremely rare (less than 1 in a million doses).

Q5: My child is healthy and we practice good hygiene. Why do we need a vaccine?

A: Measles is an airborne virus. It can linger in a room for up to two hours after an infected person has left. You cannot prevent exposure through handwashing or cleanliness alone. If an unvaccinated person walks into that room, they are highly likely to become infected. Vaccination is the only reliable defense.

Q6: What is a vaccine exemption, and how does it affect others?

A: Most states allow exemptions to school vaccine requirements for medical reasons (e.g., a severe allergy or immunocompromised state). Many also allow for religious or philosophical/personal belief exemptions. While these may seem like an issue of individual choice, they have a community impact. When enough people in a school use non-medical exemptions, the vaccination rate drops below the 95% herd immunity threshold. This creates a pocket of vulnerability where an outbreak can start, endangering children who are too young to be vaccinated or who have legitimate medical exemptions.

Q7: Where can I find reliable, trustworthy information about vaccines?

A: Stick to sources that base their information on rigorous scientific evidence. Key sources include:

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) website.

- The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP).

- The World Health Organization (WHO).

- Your own child’s pediatrician or family doctor—they are your best and most personalized resource.