In the silent, sterile corridors of a modern intensive care unit, a battle is being waged—one invisible to the naked eye but with stakes as high as any war. The soldiers are doctors, nurses, and microbiologists. The weapons are antibiotics, antivirals, and antifungals. The enemy? Bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites that have evolved to withstand our most potent medicines. This is the reality of Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR), a slow-motion pandemic that threatens to unravel a century of medical progress.

The question we confront today is not merely academic; it is a matter of life, death, and economic stability. Is the United States, despite its vast resources and scientific prowess, losing the fight against superbugs? The answer is complex, a tapestry woven with threads of groundbreaking innovation and sobering setbacks. While the U.S. has mobilized significant resources and expertise, the relentless tide of AMR in both hospital settings and our communities suggests we are, at best, fighting a precarious holding action. To lose this fight would mean a return to a pre-antibiotic era, where a simple scratch could be fatal, and routine surgeries like cesarean sections or hip replacements become prohibitively dangerous.

This article will delve into the current state of AMR in the U.S., examining the progress made, the daunting challenges that remain, and the multifaceted strategy required to avert a post-antibiotic future.

Understanding the Invisible Enemy: What is Antimicrobial Resistance?

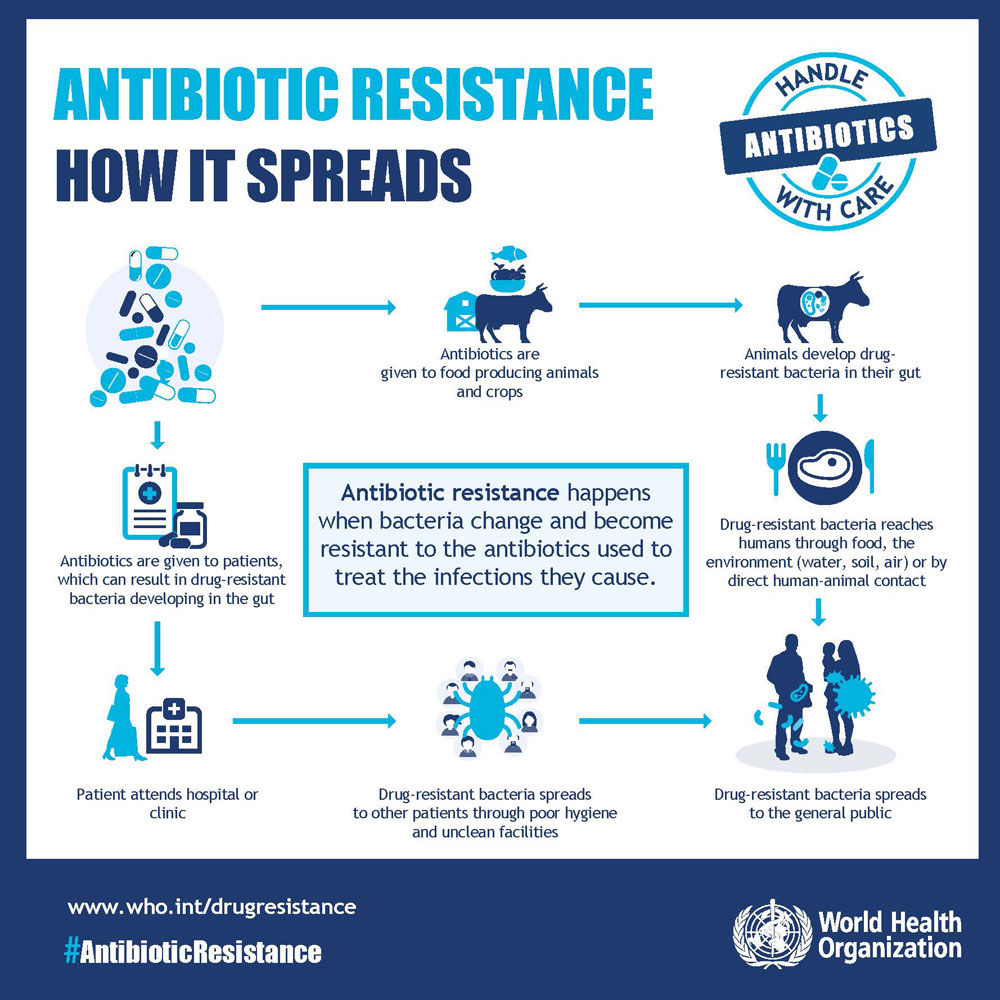

At its core, Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) is a natural evolutionary process. When microorganisms like bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites are exposed to antimicrobial drugs (like antibiotics, antivirals, etc.), the susceptible ones are killed, while the ones that survive due to random genetic mutations pass on their resistant traits. The misuse and overuse of these drugs in humans, animals, and agriculture dramatically accelerate this process.

The Scope of the Problem:

- Bacterial AMR: Often called antibiotic resistance, this is the most commonly discussed facet. “Superbugs” like Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), Vancomycin-resistant Enterococci (VRE), and Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) are prime examples.

- Antifungal Resistance: Drugs to treat fungal infections like Candida auris—a highly transmissible and often multidrug-resistant fungus—are becoming less effective.

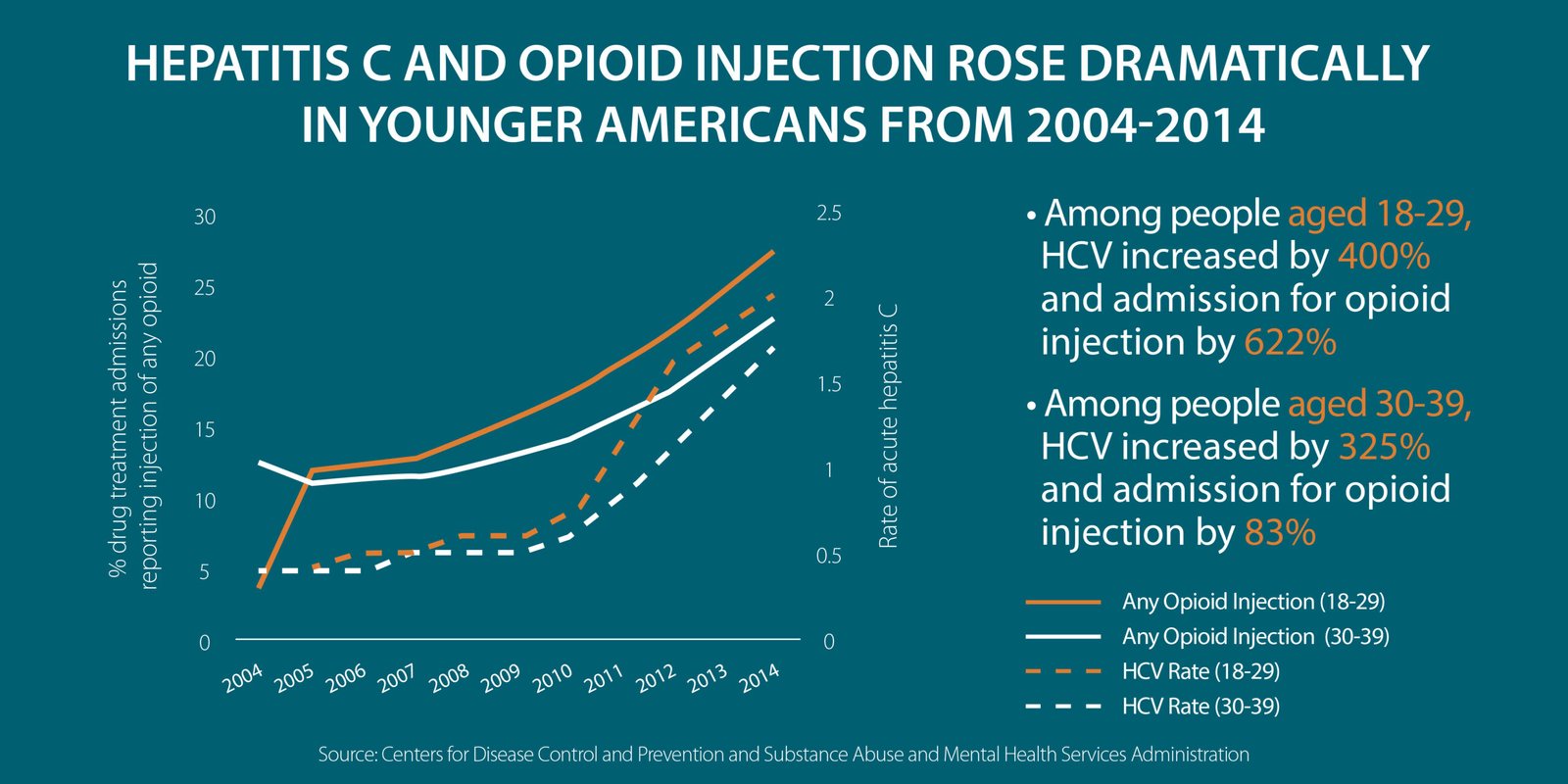

- Antiviral Resistance: Viruses like HIV and influenza can develop resistance to antiviral medications, complicating treatment regimens.

The mechanism is a brutal demonstration of “survival of the fittest.” Every time an antibiotic is used unnecessarily—for a viral cold, for instance—it provides a training ground for bacteria to develop defenses. This is compounded by the use of antibiotics in livestock to promote growth and prevent disease in crowded conditions, releasing resistant organisms into the environment.

The State of the Battlefield: AMR in U.S. Hospitals

Hospitals, the very institutions designed for healing, are epicenters for AMR. They concentrate vulnerable patients—those with compromised immune systems, surgical wounds, and invasive devices like catheters and ventilators—creating a perfect storm for the emergence and spread of superbugs.

The Frontline Foes in Hospitals:

- Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE): Dubbed “nightmare bacteria” by the CDC, CRE are resistant to nearly all available antibiotics, including carbapenems, which are often the last line of defense. Infections, particularly those causing pneumonia or bloodstream infections, have mortality rates as high as 50%.

- Candida auris: This emerging fungus is often multidrug-resistant, difficult to identify with standard laboratory methods, and has caused outbreaks in healthcare settings. It can persist on surfaces for weeks, making infection control exceptionally challenging.

- Clostridioides difficile (C. diff): While not always antibiotic-resistant in the traditional sense, C. diff thrives when antibiotics wipe out the gut’s healthy bacteria. It causes life-threatening diarrhea and is a direct consequence of antibiotic use, causing nearly 223,900 infections and 12,800 deaths in the U.S. in a single year according to CDC estimates.

Progress and Persisting Gaps in Hospital Defense:

The U.S. has made tangible strides within hospitals. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has established the National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN), which allows hospitals to track and report healthcare-associated infections (HAIs), including those caused by resistant pathogens. This data-driven approach has led to significant improvements.

Programs championing Antibiotic Stewardship Programs (ASPs) are now a standard in most acute care hospitals. These programs, led by infectious disease physicians and clinical pharmacists, ensure that patients receive the right antibiotic, at the right dose, for the right duration. The results are promising: a CDC report showed a 33% decrease in deaths from antimicrobial-resistant HAIs between 2012 and 2017.

However, the fight is far from won. The pipeline for new antibiotics is anemic. Developing a new drug is a costly, decade-long process, and the financial returns for antibiotics are poor compared to drugs for chronic conditions. A company that discovers a novel, powerful antibiotic is encouraged to not use it, to preserve its efficacy—a terrible business model. Consequently, many major pharmaceutical companies have abandoned antibiotic research. This leaves clinicians with dwindling options when faced with a pan-resistant infection.

Furthermore, infection control practices, while improved, are not uniformly implemented. Staffing shortages, especially post-pandemic, have stretched hospital resources thin, sometimes leading to lapses in basic hygiene protocols that are the first line of defense.

The Battle Beyond the Walls: AMR in the Community

While hospitals are the fortress under siege, the war is increasingly spilling into our communities. Resistant pathogens no longer confine themselves to ICU beds; they are present in gyms, schools, and our own homes.

Community-Acquired Threats:

- Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA): Once exclusively a hospital problem, MRSA is now a common cause of skin and soft tissue infections in the general population, spread through skin-to-skin contact or contaminated surfaces.

- Drug-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae: This bacterium is a leading cause of pneumonia, meningitis, and ear infections. Resistance to penicillin and other drugs complicates treatment for these common illnesses.

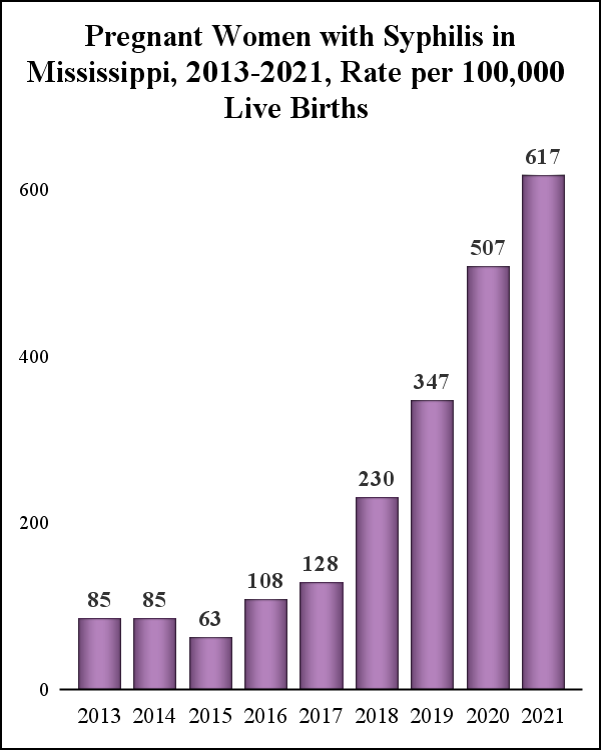

- Resistant Gonorrhea: Strains of Neisseria gonorrhoeae have developed resistance to nearly every class of antibiotic used against it. With few treatment options left, gonorrhea risks becoming an untreatable sexually transmitted infection.

- Resistant Urinary Tract Infections (UTIs): Caused by bacteria like E. coli, UTIs are increasingly resistant to standard first-line antibiotics like Bactrim and Cipro, leading to longer, more painful illnesses and a higher risk of complications like kidney infections.

Drivers in the Community:

The primary driver of community AMR is the overprescription of antibiotics. Despite decades of public health campaigns, an estimated 30% of outpatient antibiotic prescriptions in the U.S. are unnecessary. Patients often demand antibiotics for viral illnesses, and time-pressed physicians may acquiesce.

Another significant factor is the agricultural use of antibiotics. Approximately two-thirds of medically important antibiotics in the U.S. are sold for use in food-producing animals. This practice selects for resistant bacteria in livestock, which can then be transmitted to humans through the food supply, environmental contamination (water, soil), or direct animal contact.

The U.S. Response: A Multi-Pronged National Strategy

Recognizing the existential threat of AMR, the U.S. government has mounted a coordinated, if still under-resourced, response.

- The U.S. National Action Plan for Combating Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria:** This multi-agency plan, led by the CDC, FDA, and NIH, sets ambitious goals across five pillars:

- Slow the Emergence of Resistant Bacteria: Through improved antibiotic use in human and animal health.

- Strengthen National One-Health Surveillance Efforts: Tracking resistant pathogens across humans, animals, and the environment.

- Advance Development and Use of Rapid Diagnostic Tests: To quickly distinguish between bacterial and viral infections and identify resistance patterns.

- Accelerate Basic and Applied Research and Development: For new antibiotics, vaccines, and therapies.

- Improve International Collaboration and Capacity: As AMR knows no borders.

- The CDC’s Antibiotic Resistance Solutions Initiative: This initiative provides funding and expertise to state and local health departments, helping them detect, respond to, and contain resistant outbreaks. The CDC’s AMR Threat Report, updated periodically, serves as a crucial report card, quantifying the human and economic toll of AMR.

- The FDA’s Efforts: The FDA has implemented guidance to phase out the use of medically important antibiotics for growth promotion in animals. It has also created pathways like the Limited Population Pathway for Antibacterial and Antifungal Drugs (LPAD) to expedite the approval of antibiotics for limited, high-need populations.

- The NIH and Biomedical Research: The National Institutes of Health is a primary funder of basic research into the mechanisms of resistance and the discovery of novel therapeutic approaches, including phage therapy and immunotherapies.

Read more: Navigating the Maze: How to Find the Right Therapist and Understand Your Insurance in the US

The Verdict: Are We Losing?

So, is the U.S. losing the fight? The evidence points to a precarious stalemate.

We are not losing in the sense of having no defenses. Our surveillance is better than ever. Our hospitals are more aware and have stewardship programs in place. Public awareness is growing. The rapid development of mRNA vaccines for COVID-19 has demonstrated our capacity for breathtaking biomedical innovation when resources and will are aligned.

However, we are losing ground in critical areas. The pipeline of new antimicrobials is insufficient. The economic models to sustain their development are broken. The overuse of antibiotics in human and animal health continues at an alarming rate. And the rise of pan-resistant infections in the community signals that the problem is becoming more widespread and deeply entrenched.

The battle is a race between microbial evolution and human innovation. Currently, the microbes are evolving faster than our societal and economic systems can respond. We are playing an endless game of “whack-a-mole” with pathogens, and the moles are getting smarter, faster, and more numerous.

The Path to Victory: A Call to Action

To turn the tide, a paradigm shift is required. We must move from a reactive to a proactive stance. This will require:

- Reinvigorating the Antibiotic Pipeline with “Pull Incentives”: The PASTEUR Act, proposed legislation in the U.S., is a prime example. It would create a subscription-style model where the government pays developers for access to novel antibiotics, delinking their revenue from the volume sold. This guarantees a return on investment and encourages innovation without promoting overuse.

- Globalizing the Fight: AMR is the quintessential global health security threat. The U.S. must lead and invest in international efforts, supporting surveillance and stewardship in low- and middle-income countries where the burden of AMR is often highest and oversight is weakest.

- Transforming Agricultural Practices: We must accelerate the reduction of routine antibiotic use in livestock. Consumer demand for “antibiotic-free” meat is a powerful driver, but stronger regulations are also needed.

- Empowering Patients and Clinicians: Public education campaigns must be intensified. Patients need to understand that antibiotics are not a cure-all. Clinicians need better, rapid diagnostic tools at the point-of-care to make informed prescribing decisions.

- Investing in Novel Alternatives: We must dedicate significant research funding to alternatives like bacteriophage therapy, monoclonal antibodies, and vaccines that can prevent infections in the first place.

Conclusion

The fight against superbugs is one of the defining public health challenges of the 21st century. The United States has marshaled its considerable expertise and authority, establishing robust surveillance systems and stewardship programs that have saved countless lives. But the relentless march of microbial evolution, fueled by our own practices, is a formidable adversary.

We are not yet decisively losing, but we are far from winning. Victory is not guaranteed. It hinges on our collective will—to invest in innovation, to reform broken economic models, to change our behaviors, and to treat this silent pandemic with the urgency it demands. The stakes are nothing less than the foundation of modern medicine itself. The time to secure our defenses is now, before the superbugs claim an irreversible victory.

Read more: Mindful Eating: Can Your Diet Improve Your Mental Health?

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) on Antimicrobial Resistance

Q1: As a healthy person, should I be worried about AMR?

Yes, but not panicked. AMR is a population-level threat that affects everyone. Even a healthy individual can contract a resistant infection from something as simple as a minor injury, a community-acquired pneumonia, or a foodborne illness. Furthermore, the safety of common medical procedures like surgeries, cancer chemotherapy, and organ transplants relies on the ability to prevent and treat infections with effective antibiotics. If those antibiotics fail, everyone’s medical security is compromised.

Q2: I’ve heard about phage therapy. Is this a viable alternative to antibiotics?

Phage therapy—using viruses that infect and kill specific bacteria—is a promising area of research. It has been used as a last-resort treatment for some patients in the U.S. with otherwise untreatable infections. However, it is not yet a mainstream alternative. Challenges include the need to identify the perfect phage for a specific bacterial strain, the potential for bacteria to develop resistance to phages, and the regulatory pathway for approval. It is a crucial tool in the development pipeline but is not ready to replace antibiotics.

Q3: What is the single most important thing I can do to help combat AMR?

The most impactful action you can take is to use antibiotics correctly. This means:

- Never pressuring your doctor for an antibiotic for a viral illness like a cold or flu.

- Taking antibiotics exactly as prescribed, completing the entire course even if you feel better.

- Never using leftover antibiotics or sharing them with someone else.

- Practicing good hygiene—regular handwashing with soap and water—to prevent infections in the first place.

Q4: How does the use of antibiotics in animals affect me?

When antibiotics are used routinely in livestock, resistant bacteria can develop in the animals’ guts. These bacteria can then contaminate meat during slaughter and processing. They can also spread to the environment through manure and water runoff. People can be exposed by handling or eating contaminated food, or through environmental contact. This can lead to resistant infections in humans that are difficult to treat.

Q5: The COVID-19 pandemic involved incredible speed in vaccine development. Why can’t we do the same for new antibiotics?

The scientific and economic challenges are different. The COVID-19 vaccines (especially mRNA) represented a breakthrough platform technology that could be rapidly adapted for a new virus. Bacteria are more complex and diverse, requiring highly targeted approaches. Economically, vaccines are given to billions of people preventatively, creating a huge market. A new antibiotic, in contrast, is used as a last-line treatment for a limited number of patients, and its use is ideally restricted to preserve its efficacy. This makes it a financially unattractive proposition for most pharmaceutical companies without significant government incentive.

Q6: Are there any new antibiotics on the horizon?

Yes, but the pipeline is thin. A handful of new antibiotics have been approved in recent years, often targeting specific, highly resistant Gram-negative bacteria. However, most of these are variations on existing classes. Truly novel classes of antibiotics, which are needed to overcome existing resistance mechanisms, are exceedingly rare. The clinical development pipeline remains insufficient to address the breadth of the threat.

Q7: What should I do if I’m prescribed an antibiotic?

Be an active participant in your care. Ask your doctor:

- Is this antibiotic necessary? What is the evidence of a bacterial infection?

- What is the name of the antibiotic, and what bacteria does it target?

- What is the dose, and how long should I take it?

- What are the potential side effects?

- Should I report back after finishing the course, or only if problems arise?

This dialogue reinforces good stewardship and ensures you are fully informed.