For decades, Lyme disease was considered a regional problem, largely confined to the forests of the Northeast and upper Midwest. The iconic warning to “check for ticks” after a walk in the woods was a seasonal ritual for residents of Connecticut, New York, or Wisconsin, but an abstract concept for those in the Rocky Mountains or the Deep South. Today, that reality is shifting dramatically. A silent, creeping expansion is redrawing the map of tick-borne illness in the United States, pushing the boundaries of Lyme disease north into the Canadian Maritimes, west across the Ohio River Valley, and into habitats once thought unsuitable.

This article delves into the complex phenomenon of Lyme disease’s spread. We will explore the scientific evidence tracking its movement, unravel the intricate web of environmental and ecological drivers behind this expansion, and equip you with the knowledge to understand your changing local risk. This is not merely a story of a pathogen on the move; it is a story of climate change, forest fragmentation, wildlife dynamics, and human encroachment into natural spaces, culminating in a significant and growing public health challenge.

The Baseline: Understanding Lyme Disease

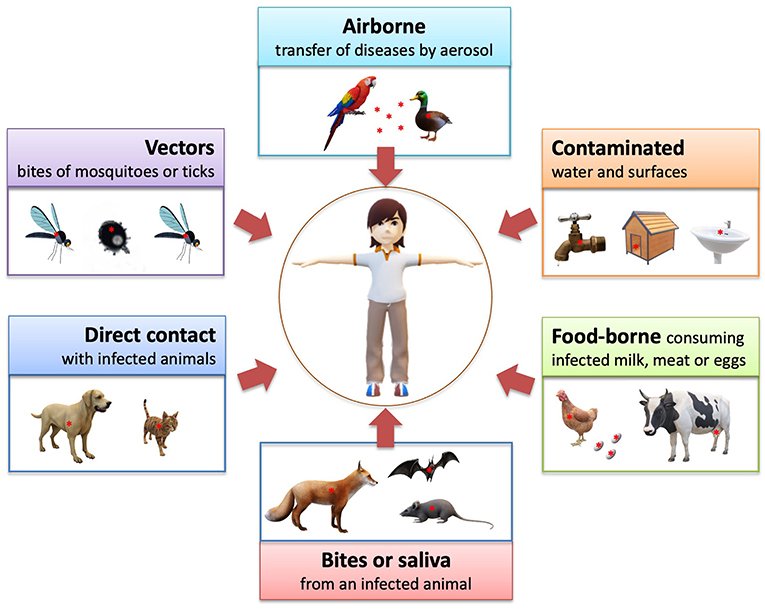

Before tracing its expansion, it’s crucial to understand what Lyme disease is. Caused by the spiral-shaped bacterium Borrelia burgdorferi (and, in some cases, the newly recognized Borrelia mayonii), Lyme disease is a vector-borne illness. This means it is transmitted not from person to person, but through the bite of an infected vector—in this case, ticks.

The Primary Vector: The Blacklegged Tick

The principal actor in the Lyme disease drama in the eastern and midwestern U.S. is the blacklegged tick, or deer tick (Ixodes scapularis). In the western U.S., the primary vector is the western blacklegged tick (Ixodes pacificus). These ticks have a two-year, three-stage life cycle: larva, nymph, and adult. They require a blood meal at each stage to progress to the next.

- Transmission Cycle: The cycle of Borrelia burgdorferi begins in wild rodents, particularly the white-footed mouse, which serves as a primary reservoir. These mice carry the bacterium in their blood with no ill effects. When a larval tick feeds on an infected mouse, it ingests the bacterium. The tick then molts into a nymph, now carrying the infection. When that nymph takes its next blood meal, it can transmit the bacterium to a new host—which could be another mouse, a bird, a deer, or a human. Adult female ticks primarily feed on larger mammals like deer to gain the energy needed to lay thousands of eggs, thus completing the cycle.

- Early Signs and Symptoms: The most recognizable early sign of Lyme disease is the erythema migrans (EM) rash, which occurs in approximately 70-80% of infected persons. It often appears at the site of the tick bite after a 3-30 day delay, expanding gradually to form a characteristic “bull’s-eye” pattern, though it can also be a solid red oval. Flu-like symptoms—fever, chills, fatigue, body aches, and headache—are also common.

- Critical Point: The tick must be attached and feeding for 36-48 hours to transmit the Lyme bacterium. Prompt and proper tick removal is a key defense.

- Later-Stage Complications: If left untreated, the infection can spread to joints, the heart, and the nervous system, leading to severe arthritis, heart palpitations, facial palsy (Bell’s palsy), and inflammation of the brain and spinal cord.

Mapping the Expansion: The Evidence of Spread

The notion that Lyme disease is spreading is not anecdotal; it is supported by robust, multi-faceted surveillance data collected by federal and state agencies.

1. The Northward March

Warmer winters are a key driver of the northward expansion. In the past, harsh, sustained cold temperatures in Canadian provinces and the northernmost U.S. states limited tick survival. While ticks do not die off en masse in a single cold snap, increasingly milder and shorter winters, with less persistent snow cover, have allowed Ixodes scapularis to establish stable populations in new territories.

- Case Study: Canada. Research published in the journal Canada Communicable Disease Report has documented the rapid northward progression of blacklegged tick populations from the northern U.S. into southern Ontario, Quebec, Manitoba, and the Maritime provinces. Established populations are now found in parts of Canada where they were absent just 20 years ago. Consequently, human Lyme disease cases in Canada have skyrocketed, from 144 cases in 2009 to over 2,500 reported cases in a recent year—a more than 1,600% increase.

- Case Study: Northern New England. States like Maine and Vermont have seen a dramatic uptick in cases. Maine, for instance, has transformed from a low-incidence state to one with hundreds of confirmed cases annually, with the tick now found in all 16 counties.

2. The Westward Push

The westward expansion is more complex but equally evident. The blacklegged tick is steadily moving across the Ohio River Valley and into states like Indiana, Illinois, Iowa, and even North Dakota. This is not a simple, uniform march but a process of “patchy colonization,” where ticks establish beachheads in suitable habitats.

- The Role of Birds: Birds are crucial “tick taxis” in this westward journey. Migratory birds, which can carry ticks hundreds of miles, drop these parasites in new locations during their seasonal travels. If the local conditions—habitat, hosts, climate—are suitable, these pioneer ticks can establish a new population.

- Surveillance Data: The CDC’s national surveillance data clearly shows this trend. Counties in states like Ohio, Michigan, and Illinois that were once considered non-endemic are now reporting established tick populations and locally acquired human cases. A 2019 study in the Journal of Medical Entomology confirmed the continued westward spread of Ixodes scapularis in the northern U.S.

3. The Changing Landscape of the South

The story in the southeastern U.S. is different but equally important. The blacklegged tick exists there, but human Lyme disease cases have historically been low. The reasons are ecological. The primary host for the larval ticks in the south is not the white-footed mouse but lizards, particularly the eastern fence lizard. A protein in the lizard’s blood has been found to kill the Borrelia bacterium, effectively cleansing the tick of infection and breaking the transmission cycle. However, research is ongoing to see if changing ecological dynamics could alter this balance.

The “Why”: Unraveling the Drivers of Expansion

The spread of Lyme disease is not a simple cause-and-effect story. It is a perfect storm of interconnected environmental and anthropogenic factors.

1. Climate Change: The Primary Accelerant

Climate change is the overarching driver facilitating this expansion in several key ways:

- Warmer Temperatures: Milder winters increase overwinter survival for ticks. Longer warm seasons also extend the active feeding period for ticks, increasing the window of risk for humans and allowing tick populations to build more rapidly.

- Changing Precipitation Patterns: Increased humidity and rainfall create the moist, leafy litter environments that ticks need to avoid desiccation. As certain regions become warmer and wetter, they become more hospitable to ticks.

- Extended Seasonal Activity: The tick season is no longer confined to spring and summer. Nymphs are active earlier, and adults remain active later into the fall and even on warm winter days, creating a nearly year-round risk in some areas.

2. Land Use Change and Forest Fragmentation

Human alteration of the landscape has unintentionally created ideal conditions for Lyme disease.

- The Suburban-Wildland Interface: As forests are broken up for housing developments and agriculture, the result is a patchwork of small woodlots. This “forest fragmentation” benefits the white-footed mouse, which is a habitat generalist and thrives in these edges. It also brings these highly efficient disease reservoirs into closer contact with humans and their pets.

- Loss of Biodiversity: A landmark concept in disease ecology is the “dilution effect.” In a diverse, intact ecosystem, ticks feed on a wide variety of animals—many of which, like the opossum, are inefficient at transmitting Borrelia and may even groom off and kill a large number of ticks. When biodiversity declines, and generalist species like the white-footed mouse dominate, the rate of infected ticks increases. The mouse is a super-efficient reservoir, infecting up to 90% of the ticks that feed on it.

3. Wildlife Population Shifts

The resurgence of white-tailed deer populations in the 20th century is a critical piece of the puzzle. While deer are not competent reservoirs for the Lyme bacterium (they do not infect feeding ticks), they are the primary host for adult ticks. A robust deer population supports a massive reproductive engine for the tick population. Furthermore, the movement of deer, often through suburban corridors, helps disperse ticks into new areas.

The Human Impact: A Growing Public Health Burden

The expansion of Lyme disease translates directly to a growing human and economic toll.

- Rising Case Numbers: The CDC estimates that approximately 476,000 Americans are diagnosed and treated for Lyme disease each year. This figure, based on insurance claims data, is significantly higher than the number of officially reported cases, highlighting the scale of the problem.

- Diagnostic Challenges: Lyme disease is notoriously difficult to diagnose. The two-tiered antibody testing can produce false negatives, especially in the early stages of infection before the body has produced detectable antibodies. As the disease moves into new areas where physicians are less familiar with it, the risk of misdiagnosis and delayed treatment increases, leading to more severe late-stage complications.

- The Burden of Chronic Symptoms: A subset of patients (often referred to as having Post-Treatment Lyme Disease Syndrome or PTLDS) continue to experience debilitating symptoms like fatigue, widespread pain, and cognitive difficulties for months or even years after completing standard antibiotic treatment. The cause of these persistent symptoms is not fully understood and is an area of intense research and debate.

- Economic Cost: A 2021 study published in the Journal of Public Health estimated the annual economic burden of Lyme disease in the U.S. to be between $786 million and $1.3 billion, accounting for healthcare costs, lost productivity, and diminished quality of life.

Read more: Beyond Burnout: Understanding and Managing Chronic Stress in the American Workplace

Mitigation and Personal Protection: A Multi-Layered Defense

In the face of this expanding threat, a multi-pronged approach is essential, combining personal vigilance, landscape management, and public health initiatives.

Personal Protection is Your First Line of Defense:

- Use EPA-Registered Repellents: Apply repellents containing DEET, picaridin, IR3535, or Oil of Lemon Eucalyptus (OLE) to exposed skin. Treat clothing and gear with permethrin, which kills ticks on contact.

- Wear Protective Clothing: In tick habitats, wear long sleeves, long pants, and tuck your pants into your socks. Light-colored clothing makes it easier to spot ticks.

- Stay on Trails: Avoid walking through tall grasses, brush, and leaf litter where ticks wait to latch onto a host.

- Perform Daily Tick Checks: The most critical step. Conduct a full-body tick check on yourself, your children, and your pets after spending time outdoors. Pay close attention to hidden areas: underarms, in and around ears, inside the belly button, behind knees, and in the groin area.

- Shower Soon After Being Outdoors: This can help wash off unattached ticks and provides a good opportunity for a check.

- Tumble Dry Clothes: Placing dry clothes in a dryer on high heat for 10 minutes can kill any remaining ticks.

Landscape Management for Homeowners:

- Create a 3-foot-wide barrier of wood chips or gravel between lawns and wooded areas.

- Keep lawns mowed and clear leaf litter, tall grasses, and brush.

- Stack wood neatly and in a dry area to discourage rodent activity.

- Consider using acaricides (tick pesticides), applied by a professional, to control ticks in your yard.

The Future: Research and Public Health Initiatives

Combating this expansion requires a sustained effort:

- Enhanced Surveillance: Continued funding for state and federal programs to track tick populations and human cases is vital for understanding the speed and direction of the spread.

- Vaccine Development: After the withdrawal of the first-generation Lyme vaccine (LYMErix) in the early 2000s, the field is seeing renewed interest. Pfizer and Valneva are in late-stage clinical trials with a promising new vaccine candidate, VLA15. Research is also underway for a vaccine that targets tick proteins, which could potentially block transmission of multiple tick-borne pathogens.

- Public and Physician Education: Raising awareness in newly endemic areas is crucial. Healthcare providers need to be educated on the changing epidemiology and the symptoms of Lyme and other tick-borne diseases to ensure prompt diagnosis and treatment.

Conclusion

The northward and westward spread of Lyme disease is a clear and present warning of how interconnected our world is. The health of our ecosystems is inextricably linked to our own public health. The expansion is driven not by a single factor, but by a cascade of human-induced changes—from the carbon emissions warming our planet to the ways we fragment our forests.

This is not a reason to retreat from the natural world, which is essential for our physical and mental well-being. Instead, it is a call for heightened awareness, proactive personal protection, and sustained investment in scientific research and public health infrastructure. The map of Lyme disease risk is being redrawn. Understanding the forces behind this change is the first step in protecting ourselves, our families, and our communities from this growing threat.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) Section

Q1: I live in a state that has never had a Lyme problem before. Should I be concerned now?

A: Yes, it’s wise to be vigilant. The range of the blacklegged tick is expanding into many states previously considered low-risk. Check the most recent maps from the CDC or your state’s Department of Public Health to understand your local risk, which can change yearly. Even if your state is not yet considered “endemic,” localized tick populations can establish, and migratory birds can drop infected ticks into your area.

Q2: What is the single most effective thing I can do to prevent Lyme disease?

A: The single most effective strategy is to perform a thorough, daily tick check after spending time outdoors. Because a tick typically needs to be attached for 36-48 hours to transmit the Lyme bacterium, finding and removing it promptly is the best way to prevent infection. Combine this with using repellents and wearing protective clothing for a layered defense.

Q3: I found a tick attached to me. What should I do?

A: Don’t panic. Use fine-tipped tweezers to grasp the tick as close to the skin’s surface as possible. Pull upward with steady, even pressure. Do not twist or jerk the tick, as this can cause its mouth-parts to break off and remain in the skin. After removal, clean the bite area and your hands with rubbing alcohol or soap and water. Flush the tick down the toilet or, if you wish to have it identified, place it in a sealed bag or container. You can take a photo and use online tick identification tools or contact your local health department.

Q4: Should I get the tick tested for Lyme disease?

A: The CDC does not recommend testing individual ticks for several reasons. A positive test on a tick does not necessarily mean you are infected, as transmission requires sufficient feeding time. Conversely, a negative test might provide false reassurance, as the tick could be carrying other pathogens. The most reliable approach is to monitor your health for symptoms and consult your healthcare provider immediately if any, such as a rash or fever, develop.

Q5: I have flu-like symptoms and a rash, but I never saw a tick. Could it still be Lyme?

A: Absolutely. Nymphal ticks are incredibly small—about the size of a poppy seed—and are easily missed. Furthermore, the EM rash does not always have a bull’s-eye appearance and may not occur at the bite site. If you develop flu-like symptoms during tick season and have spent time in a tick-prone habitat, you should see a doctor and specifically mention the possibility of Lyme disease.

Q6: Is chronic Lyme disease a real condition?

A: This is a complex and sometimes contentious area. The medical and scientific consensus, as held by organizations like the CDC and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA), is that there is no evidence of persistent, active infection in patients who have received the recommended course of antibiotics for Lyme disease. However, they do recognize that a subset of patients (estimated at 5-15%) experience lingering symptoms like fatigue and pain after treatment, a condition termed Post-Treatment Lyme Disease Syndrome (PTLDS). The cause of PTLDS is unknown and is the subject of ongoing research. It is distinct from “Chronic Lyme Disease,” which is not a medically accepted diagnosis but is often used by patients and some practitioners to describe a wider set of persistent symptoms.

Q7: Are there other tick-borne diseases I should worry about?

A: Yes, unfortunately. Different ticks can transmit different diseases, and some ticks can carry and transmit multiple pathogens in a single bite—a phenomenon known as co-infection. Other significant tick-borne illnesses in the U.S. include:

- Anaplasmosis and Ehrlichiosis: Bacterial infections causing flu-like symptoms.

- Babesiosis: A malaria-like illness caused by microscopic parasites that infect red blood cells.

- Powassan Virus: A rare but serious viral disease that can cause encephalitis.

- Alpha-gal Syndrome: An allergic reaction to red meat caused by the bite of the Lone Star tick.

This makes tick prevention and prompt removal all the more critical.

Q8: What is the status of a new Lyme disease vaccine?

A: As of late 2023, the most advanced candidate is VLA15, developed by Pfizer and Valneva. It is in Phase 3 human trials and has shown a strong immune response in previous studies. If approved, it would be the only vaccine on the market for Lyme disease. However, it is still at least a few years away from potential public availability. Researchers are also exploring novel approaches, such as vaccines that target tick saliva to prevent transmission of multiple pathogens.