Introduction: A Nation in Discomfort

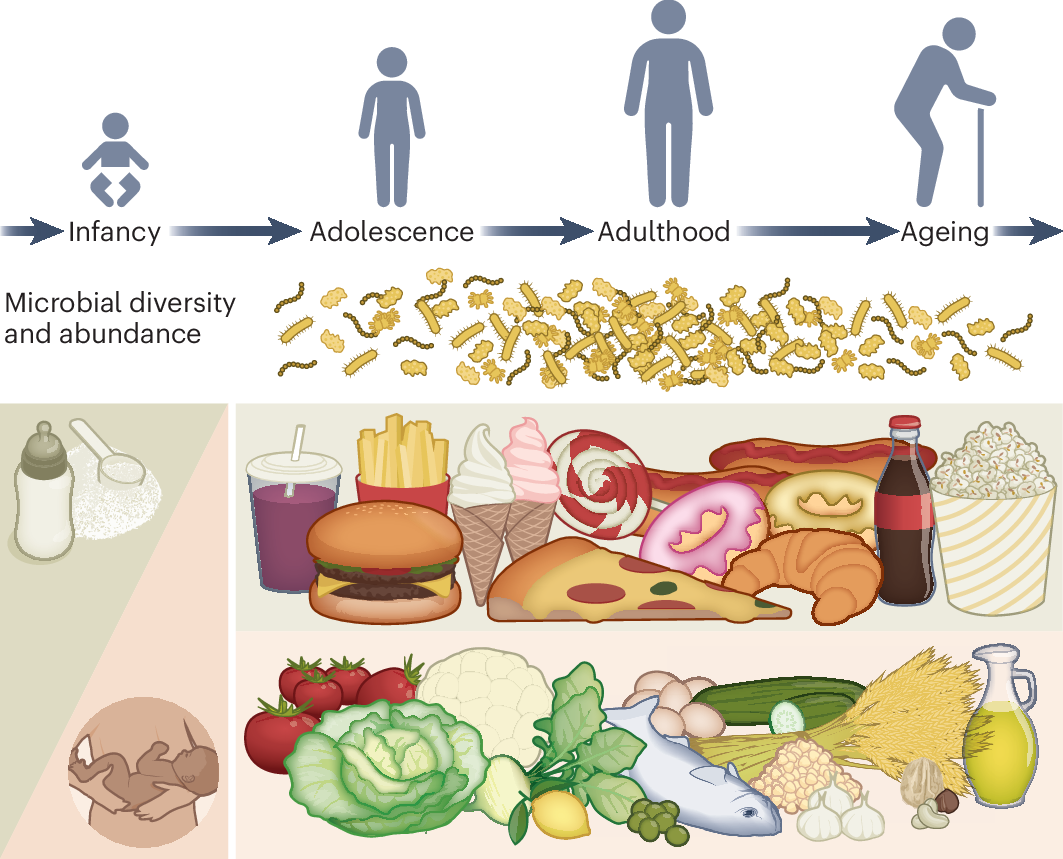

If you frequently experience abdominal cramping, bloating, gas, and unpredictable swings between constipation and diarrhea, you are far from alone. In the United States, Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) is not just a personal discomfort; it is a widespread public health crisis, affecting an estimated 10-15% of the population, or between 25 and 45 million people. For a condition that was once shrouded in stigma and dismissed as “nerves,” the sheer scale of its prevalence demands a deeper explanation.

The answer, a growing body of research suggests, may be on our plates. The Standard American Diet (SAD)—characterized by its high intake of processed foods, refined sugars, unhealthy fats, and low intake of dietary fiber—has created a perfect storm for digestive distress. This isn’t about a single “bad” food, but rather a systemic dietary pattern that disrupts the very foundations of our gut health.

This article serves as a comprehensive “gut check.” We will explore the intricate physiology of IBS, dissect how the pillars of the SAD directly attack our digestive system, and provide an evidence-based, actionable roadmap to healing. By understanding the connection between what we eat and how we feel, we can begin to reverse the tide of this modern epidemic.

Part 1: Understanding IBS – More Than Just a “Nervous Stomach”

Before we can understand the diet’s role, we must first define the condition. Irritable Bowel Syndrome is a functional gastrointestinal (GI) disorder. This means it’s a problem with how the gut-brain axis works, rather than a disease that can be seen with standard tests like a colonoscopy or biopsy.

1.1 What is IBS? The Rome IV Criteria

Diagnosis is typically made using the Rome IV criteria, which require the presence of recurrent abdominal pain, on average, at least one day per week in the last three months, associated with two or more of the following:

- Related to defecation.

- Associated with a change in frequency of stool.

- Associated with a change in form (appearance) of stool.

IBS is commonly sub-typed based on the predominant stool pattern:

- IBS-C (Constipation-predominant): Hard or lumpy stools more than 25% of the time.

- IBS-D (Diarrhea-predominant): Loose or watery stools more than 25% of the time.

- IBS-M (Mixed): Alternating between constipation and diarrhea.

- IBS-U (Unclassified): For those who don’t fit the above categories.

1.2 The Underlying Mechanisms: Why Does IBS Happen?

While the exact cause is multifactorial, several key mechanisms are at play in most individuals with IBS:

- Visceral Hypersensitivity: The nerves in the gut of someone with IBS are often overly sensitive. What most people would perceive as normal gas or mild fullness can be registered by the IBS brain as significant pain or discomfort.

- Altered Gut Motility: The rhythmic contractions (peristalsis) that move food through the digestive tract can be too fast (leading to diarrhea) or too slow (leading to constipation).

- The Gut-Brain Axis Dysregulation: This is a critical two-way communication network between the central nervous system and the enteric nervous system (the “second brain” in the gut). In IBS, this communication is faulty. Stress and anxiety can trigger gut symptoms, and gut symptoms, in turn, can cause anxiety and stress, creating a vicious cycle.

- Dysbiosis: An imbalance in the gut microbiota—the community of trillions of bacteria, viruses, and fungi living in our intestines—is a hallmark of IBS. A healthy, diverse microbiome is essential for proper digestion, immune function, and even nerve signaling. In dysbiosis, harmful microbes may outnumber beneficial ones, leading to inflammation, gas production, and impaired gut barrier function.

Read nore: 10 Signs Your Gut Health Is Out of Balance (and How to Fix It)

Part 2: The SAD Assault – How the Standard American Diet Breaks the Gut

The Standard American Diet is not merely defined by what it lacks, but by what it contains in excess. Its components work synergistically to disrupt the delicate balance of the digestive system.

2.1 The Low-Fiber, High-Refined-Carbohydrate Problem

The SAD is notoriously low in dietary fiber, with most Americans consuming only about 15 grams per day, far below the recommended 25-38 grams.

- The Role of Fiber: Fiber, particularly soluble fiber, acts as a prebiotic—food for our beneficial gut bacteria. It also adds bulk to stool, softens it, and helps regulate bowel movements.

- The Consequences of Deficiency: A low-fiber diet starves the good bacteria, allowing less desirable microbes to thrive (dysbiosis). This leads to harder, less frequent stools (constipation) and reduces the production of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) like butyrate, which are crucial for reducing gut inflammation and maintaining the health of the colon lining.

- The Sugar and White Flour Onslaught: Meanwhile, the diet is high in refined carbohydrates (white bread, pasta, pastries, sugar). These are rapidly broken down and absorbed in the small intestine, providing a feast for sugar-loving bacteria and yeast (like Candida), which can produce excessive gas and contribute to bloating and discomfort.

2.2 The FODMAP Pile-Up

This is one of the most significant and specific links between the SAD and IBS symptoms. FODMAP is an acronym for Fermentable Oligosaccharides, Disaccharides, Monosaccharides, and Polyols. These are short-chain carbohydrates that are poorly absorbed in the small intestine.

- What They Do: Because they are not absorbed, they travel to the large intestine, where they act as a potent food source for gut bacteria. The bacteria ferment them, producing gas, which leads to bloating, distension, and pain, especially in a gut with visceral hypersensitivity.

- Why the SAD is High in FODMAPs: The modern Western diet is loaded with high-FODMAP foods.

- Oligosaccharides (Fructans & GOS): Found in wheat, onions, garlic, and beans.

- Disaccharides (Lactose): Found in milk and soft cheeses.

- Monosaccharides (Fructose): Found in excess of glucose in foods like honey, agave, and high-fructose corn syrup (HFCS), a ubiquitous sweetener in sodas and processed foods.

- Polyols (Sugar Alcohols): Found in some fruits and vegetables (e.g., avocados, cauliflower) and used as artificial sweeteners in “sugar-free” products (e.g., sorbitol, mannitol).

The cumulative effect of a high-FODMAP diet on a susceptible individual can be devastating, providing a constant source of fermentable fuel for uncomfortable gas production.

2.3 The Fat Factor: Quality and Quantity Matters

Dietary fat is not the enemy, but the type and amount common in the SAD are problematic.

- Inflammatory Fats: The SAD is high in omega-6 fatty acids (from industrial seed oils like soybean, corn, and canola oil) and trans fats (from partially hydrogenated oils, though now banned, their effects linger). These fats promote systemic inflammation, which can exacerbate gut sensitivity and pain.

- High-Fat Meals: Large amounts of fat, particularly saturated fat from fried foods and fatty meats, can trigger strong gastrocolic reflexes, leading to urgent bowel movements and diarrhea in people with IBS-D.

2.4 Food Additives and Emulsifiers: Disrupting the Ecosystem

The processed foods that form the backbone of the SAD are filled with additives designed to improve texture and shelf-life. Emerging research suggests these may be directly harming our gut.

- Emulsifiers like polysorbate 80 and carboxymethylcellulose (cellulose gum) have been shown in animal studies to thin the protective mucus layer of the gut and promote bacterial encroachment onto the gut lining, potentially contributing to “leaky gut” (increased intestinal permeability) and inflammation.

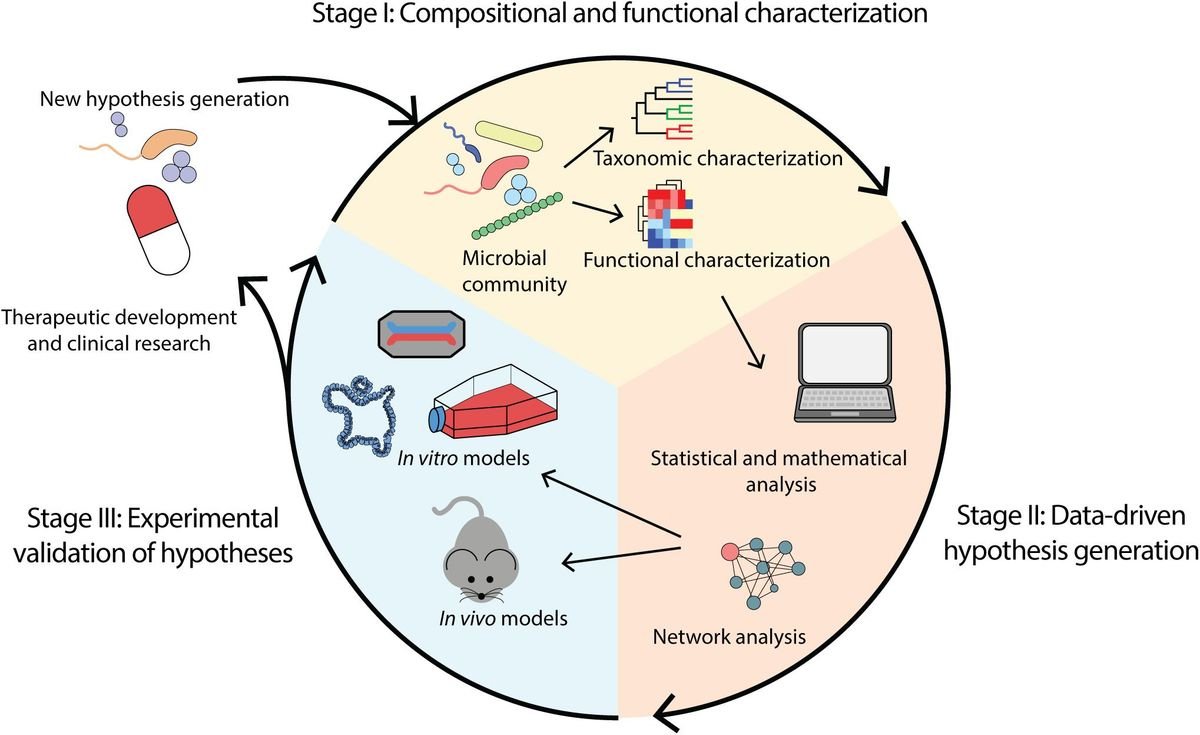

Part 3: The Vicious Cycle – Diet, Dysbiosis, and Dysfunction

These dietary factors don’t operate in isolation. They create a self-perpetuating cycle that is difficult to break without intervention.

- The Diet Initiates Dysbiosis: A diet low in fiber and high in sugar and processed foods disrupts the healthy gut microbiome.

- Dysbiosis Leads to Symptoms: The imbalanced microbiome produces excess gas, contributes to inflammation, and may impair the gut barrier.

- Symptoms Cause Stress: The pain, bloating, and unpredictability of IBS cause significant anxiety and stress.

- Stress Worsens Gut Function: Through the gut-brain axis, stress further alters gut motility, increases visceral sensitivity, and can negatively impact the microbiome, making the gut even more reactive to the problematic diet.

- The Cycle Repeats: The individual, feeling stressed and unwell, may reach for convenient, comforting—but often gut-disrupting—SAD foods, perpetuating the cycle.

Part 4: The Road to Recovery – An Actionable Plan for a Healthier Gut

Breaking the cycle requires a strategic, multi-faceted approach focused on nourishing the gut and calming the nervous system.

4.1 The First Step: The Low-FODMAP Diet (A Short-Term Diagnostic Tool)

The Low-FODMAP diet is a three-phase elimination diet, not a lifelong way of eating. It should be undertaken, ideally, with the guidance of a Registered Dietitian (RD).

- Phase 1: Elimination: All high-FODMAP foods are removed from the diet for a strict 2-6 weeks. The goal is to see if symptoms significantly improve, which confirms FODMAPs as a trigger.

- Phase 2: Reintroduction: FODMAP groups are systematically reintroduced, one at a time, to identify which specific types (e.g., fructans, lactose) and what amounts trigger symptoms. This is the most crucial phase for personalization.

- Phase 3: Personalization (The Modified Low-FODMAP Diet): Based on the reintroduction results, a long-term diet is created that is as liberal as possible, only restricting the specific FODMAPs and in the amounts that cause symptoms.

4.2 Foundational Dietary Shifts: Building a Gut-Friendly Plate

Beyond FODMAPs, these principles are essential for long-term gut health:

- Prioritize Soluble Fiber: During stable periods, focus on incorporating soluble fiber from low-FODMAP sources like oats, psyllium husk, oranges, strawberries, carrots, and potatoes. Soluble fiber is generally well-tolerated and helps regulate bowel movements.

- Mindful Fat Intake: Choose anti-inflammatory fats like olive oil, avocado oil, and the fats in fatty fish (salmon, mackerel). Be mindful of large, greasy meals.

- Hydrate Wisely: Drink plenty of water throughout the day, but avoid large amounts with meals, which can speed transit. Limit carbonated beverages, which can contribute to gas.

- Eat Regularly, Chew Thoroughly: Avoid skipping meals, which can disrupt motility. Chewing food completely is the first and critical step of digestion, reducing the workload on the rest of the GI tract.

4.3 The Role of Supplements and Probiotics

- Peppermint Oil: Enteric-coated peppermint oil capsules have strong evidence for relieving abdominal pain and bloating in IBS by acting as an antispasmodic on the smooth muscles of the gut.

- Probiotics: The evidence is mixed, but certain strains, particularly Bifidobacterium infantis 35624, have shown promise in reducing overall IBS symptoms, bloating, and bowel habit disturbance. It’s not a one-size-fits-all solution, so working with a professional can help you find the right strain.

- Psyllium Husk: A soluble fiber supplement like psyllium can be incredibly effective for both IBS-C and IBS-D, helping to normalize stool consistency.

4.4 Addressing the Gut-Brain Connection

- Stress Management is Non-Negotiable: Techniques like cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), gut-directed hypnotherapy (which has excellent evidence for IBS), meditation, and regular moderate exercise (like walking or yoga) can lower stress, improve visceral hypersensitivity, and re-regulate the gut-brain axis.

When to See a Doctor

It is crucial to receive a formal diagnosis from a gastroenterologist to rule out other conditions like Celiac Disease, Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD), or colon cancer.

Seek immediate medical attention for “red flag” symptoms such as:

- Unintentional weight loss

- Rectal bleeding or black, tarry stools

- Persistent vomiting

- Unexplained iron-deficiency anemia

- A family history of IBD or colon cancer

- Symptoms that begin after age 50

Conclusion: Reclaiming Your Gut Health is Possible

The IBS epidemic in America is, in large part, a man-made problem, fueled by a diet that is fundamentally at odds with our digestive physiology. The Standard American Diet disrupts our microbial ecosystem, irritates our intestinal lining, and dysregulates our gut-brain communication.

But this knowledge is empowering. It means that by changing what we eat, we are not just addressing symptoms; we are addressing the root cause of the dysfunction for millions. The path forward requires moving away from processed, industrial foods and toward a personalized, whole-foods-based way of eating that honors the complexity of our gut. By conducting our own “gut check,” we can move from a state of constant discomfort to one of resilience and well-being, one mindful bite at a time.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q1: Is IBS caused by gluten?

For most people, no. True Celiac Disease, an autoimmune reaction to gluten, must be ruled out by a doctor. However, many people with IBS are sensitive to the fructans (a type of FODMAP) found in wheat, not the gluten protein itself. This is why they feel better on a low-FODMAP diet that reduces wheat, not necessarily a strict gluten-free diet.

Q2: I’ve heard about “leaky gut.” Is that real and is it related to IBS?

Increased Intestinal Permeability (“leaky gut”) is a real physiological phenomenon where the tight junctions between cells in the gut lining become loose, potentially allowing undigested food particles and bacteria into the bloodstream, triggering inflammation. While it is not yet officially recognized as a standalone diagnosis, a growing body of research links it to IBS and other inflammatory conditions. The components of the SAD (high sugar, emulsifiers, dysbiosis) are known to contribute to increased permeability.

Q3: Can the Low-FODMAP diet cure my IBS?

The Low-FODMAP diet is a management strategy, not a cure. Its primary goal is to identify food triggers to achieve significant symptom control. For many, this control is life-changing. However, “success” is defined in the personalization phase, where you liberate your diet as much as possible based on your unique tolerances.

Q4: Are probiotics a good idea for everyone with IBS?

Not necessarily. Probiotics can be helpful for some, but for others, particularly those with a condition called SIBO (Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth), they can potentially worsen symptoms. It’s best to approach probiotics strategically. Start with a single, well-researched strain, monitor your symptoms, and consider working with a healthcare provider to determine if they are right for you.

Q5: I feel overwhelmed. Where should I start?

Start with one small, sustainable change. Do not attempt a full Low-FODMAP elimination on your own. A great first step is to:

- Increase soluble fiber: Add one tablespoon of psyllium husk to your diet daily.

- Reduce obvious triggers: Cut back on soda, sugary snacks, and deep-fried foods.

- Eat mindfully: Slow down and chew your food thoroughly.

- Consult a professional: Schedule an appointment with a gastroenterologist for a formal diagnosis and a Registered Dietitian (RD) who specializes in GI health to guide you personally.

Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only and is based on current scientific literature and clinical guidelines from reputable sources such as the American College of Gastroenterology and Monash University, the pioneers of FODMAP research. It is not intended to provide medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always consult with a qualified healthcare professional, such as a gastroenterologist or Registered Dietitian, before making any changes to your diet, lifestyle, or treatment plan. Never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read in this article.

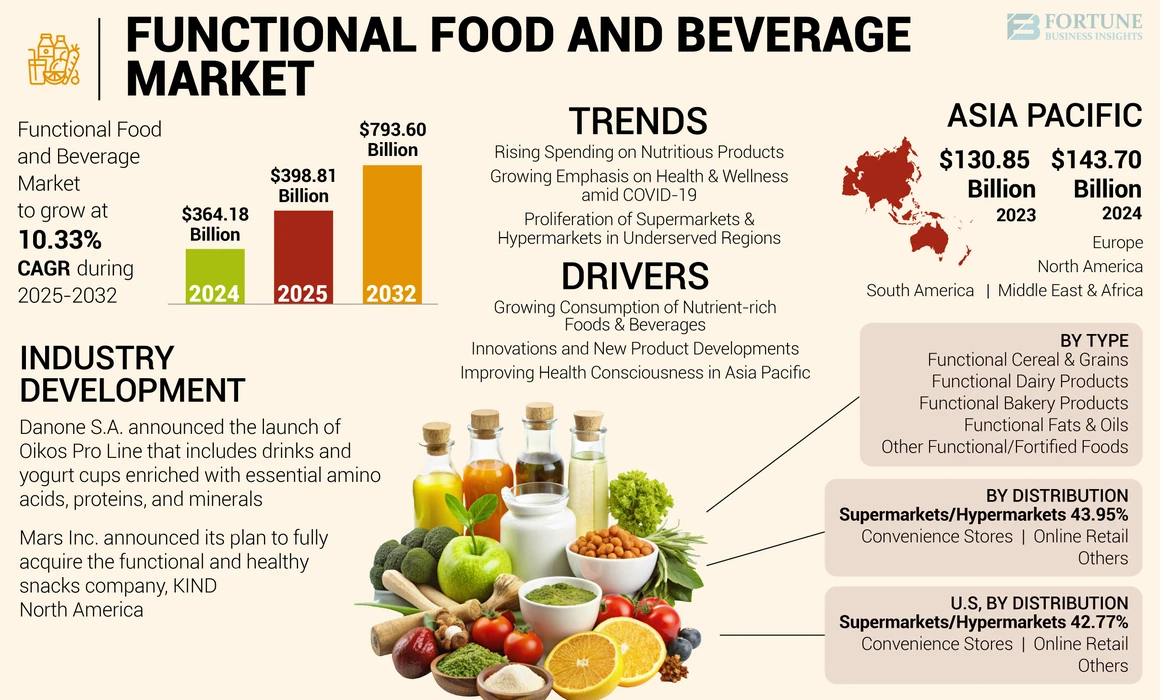

Read more: Rise of Probiotics, Prebiotics, and Synbiotics: America’s Gut Health Revolution