The COVID-19 pandemic was more than a global health crisis; it was a brutal, real-time stress test of the United States’ public health infrastructure. A system long revered for its scientific prowess and historic achievements was revealed to be fragmented, underfunded, and perilously unprepared for a 21st-century threat. The years since the initial shock have been a period of intense scrutiny, painful reckoning, and, crucially, transformation. The pandemic did not just expose weaknesses; it acted as a powerful, if traumatic, catalyst for change. This article examines the profound and lasting ways COVID-19 has reshaped America’s public health infrastructure, from data modernization and supply chain logistics to workforce development and the very relationship between public health and the public it serves. We will explore the lessons learned, the reforms underway, and the critical challenges that remain in building a more resilient system for the future.

Section 1: The Pre-Pandemic Foundation – Cracks in the Pillars

To understand the transformation, one must first appreciate the pre-existing conditions. For decades, America’s public health system operated as a decentralized network, often described as a “patchwork quilt.” Its core pillars—the federal agencies (primarily the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Department of Health and Human Services), state health departments, and approximately 2,800 local health departments—were often siloed, under-resourced, and reliant on outdated technologies.

1.1 Chronic Underinvestment:

Public health is often a victim of its own success. When diseases are prevented, the crisis is averted, and funding becomes politically difficult to justify. Between 2008 and 2019, spending on state public health departments dropped by 16%, and local health departments lost nearly 30% of their workforce capacity. This “boom-and-bust” cycle of funding—surges during emergencies like H1N1 or Zika, followed by steep declines—left the system without a stable foundation for long-term preparedness.

1.2 Antiquated Data Systems:

Perhaps the most glaring failure was in data. In 2020, the world’s largest economy was still relying on a patchwork of fax machines, phone calls, and archaic software for disease surveillance. The CDC’s data collection from states was slow, incomplete, and incompatible, creating a lag of days or even weeks in understanding the virus’s spread. This data blindness crippled the national response, making it impossible to allocate resources efficiently or implement targeted interventions.

1.3 The Erosion of Public Trust:

Years of declining social capital and the rise of misinformation set the stage for a crisis of confidence. Public health authorities, once largely trusted, found their messages drowned out by a cacophony of conflicting information from political figures, social media, and partisan news outlets. The stage was set for a perfect storm.

Section 2: The Crucible – Key Failures That Forced Change

The pandemic subjected this fragile system to extreme pressure, revealing specific, critical failures that have since become the primary focus of reform.

2.1 The Data Breakdown:

The inability to track the virus in real time was a catastrophic early failure. The lack of standardized, interoperable data systems meant that case counts, hospitalization rates, and test positivity were often incomplete and delayed. This forced reliance on proxy metrics, such as wastewater surveillance, which, while innovative, highlighted the deficiency in primary data streams. The lesson was clear: in a fast-moving pandemic, data is not just information; it is the oxygen that fuels an effective response.

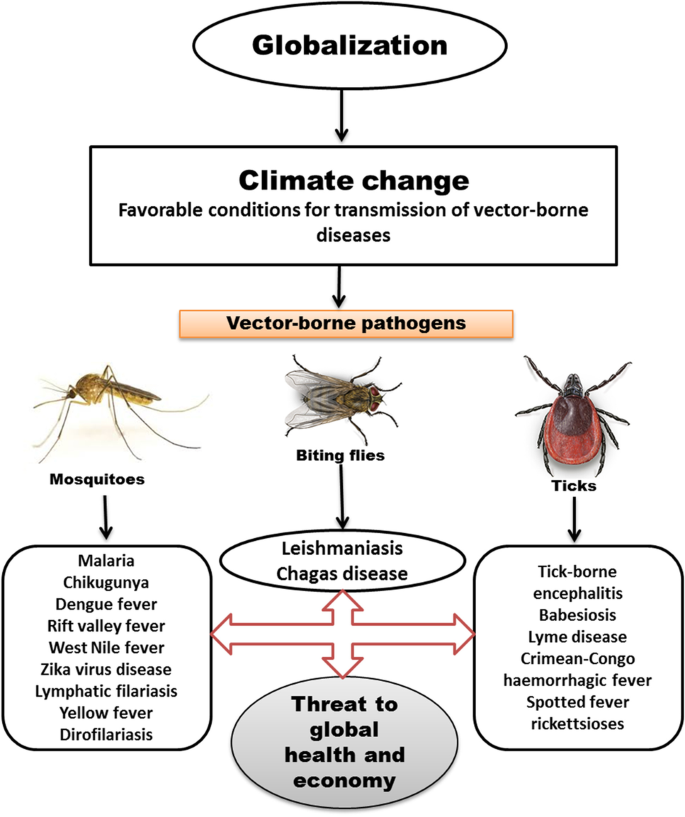

2.2 The Supply Chain Catastrophe:

The collapse of the medical supply chain was a shocking revelation of globalization’s vulnerabilities. The just-in-time inventory model, designed for efficiency, proved disastrous for resilience. Shortages of N95 masks, gloves, ventilators, and even simple swabs brought healthcare systems to the brink. It exposed an over-reliance on overseas manufacturing and a stunning lack of national strategic stockpile preparedness for a sustained crisis.

2.3 The Public Health Workforce Crisis:

The “boots on the ground” of public health—epidemiologists, contact tracers, public health nurses—were thrust into an impossible situation. Already stretched thin, they faced overwhelming caseloads, vitriol from a skeptical public, and burnout on an unprecedented scale. A staggering exodus from the field followed, with over 40% of state and local public health staff leaving their jobs between 2017 and 2021. The human infrastructure of public health was breaking.

2.4 The Communication Collapse:

Mixed messaging from federal, state, and local leaders, coupled with the rapid spread of misinformation online, severely undermined the pandemic response. Guidelines on masks, lockdowns, and vaccines evolved as the science did, but this necessary nuance was weaponized to paint public health officials as inconsistent or untrustworthy. The failure was not just in the science, but in the science of communication.

Section 3: The Reshaping – A System Undergoing Reinvention

In response to these failures, a multi-faceted transformation of America’s public health infrastructure is underway. This reshaping is happening at federal, state, and local levels, driven by new funding, new policies, and a hard-won new awareness.

3.1 The Data Modernization Initiative (DMI):

Recognizing the critical need for better data, the CDC launched an ambitious, multi-billion dollar Data Modernization Initiative (DMI). This is arguably the most significant structural change post-pandemic. Its goals are to:

- Create Interoperability: Establish common data standards so that systems at hospitals, labs, and health departments can “talk” to each other seamlessly.

- Move to Real-Time Reporting: Shift from batch-processed, delayed data to real-time or near-real-time electronic reporting.

- Enhance Analytic Capacity: Invest in cloud computing and advanced analytics to detect outbreaks earlier and model future trends.

- Expand Data Sources: Formalize and integrate non-traditional data sources, such as wastewater surveillance and syndromic surveillance (tracking symptoms from ER visits), into the core public health arsenal.

3.2 Rebuilding the Strategic National Stockpile (SNS):

The SNS has undergone a fundamental rethink. The new model moves beyond a static repository of supplies to a dynamic, “warm-based” inventory management system. Key changes include:

- Diversifying Suppliers: Reducing reliance on single-source, overseas manufacturers by onshoring and friendshoring critical production.

- Implementing Rotating Stock: Creating a system for rotating and replenishing supplies to avoid expiration.

- Enhancing Predictive Analytics: Using data to predict demand and pre-position supplies based on emerging hotspots.

- Investing in Next-Gen Technologies: Stockpiling raw materials for vaccines and tests that can be rapidly activated against new pathogens (“Disease X”).

3.3 Reinvesting in the Public Health Workforce:

Billions of dollars from the American Rescue Plan and subsequent legislation have been allocated to shore up the public health workforce. This investment focuses on:

- Recruitment and Retention: Offering loan repayment programs, competitive salaries, and career ladder opportunities to attract and retain talent.

- Burnout Prevention and Mental Health Support: Acknowledging the immense psychological toll on public health workers and providing necessary resources.

- Training and Upskilling: Creating new pipelines through partnerships with universities and providing ongoing training in crisis leadership, health equity, and modern data science.

3.4 The Centralization vs. Decentralization Debate:

The pandemic sparked a fierce debate about the optimal structure of public health authority. Some states have moved to centralize power in the governor’s office, arguing it creates a more streamlined, efficient response. Others have sought to protect the autonomy of local health departments, arguing that hyper-local knowledge is essential for effective, culturally competent interventions. This tension between top-down command and bottom-up agility remains a central challenge in the reshaped landscape.

Read more: Digital Detox: Reclaiming Your Focus and Improving Your Mood in a Hyper-Connected USA

Section 4: The Enduring Challenges and the Road Ahead

Despite this progress, significant challenges threaten to undermine the rebuilding efforts. The post-pandemic landscape is not just one of reform, but also of continued vulnerability.

4.1 The Politicalization of Public Health:

Public health has become a partisan battleground. Mask mandates, vaccine requirements, and business closures were framed not as evidence-based measures but as issues of personal freedom versus government overreach. This politicalization has led to legislation in several states that curtails the emergency powers of public health officials, making it harder to respond swiftly to the next crisis. Rebuilding trust in non-partisan scientific institutions is perhaps the single greatest long-term challenge.

4.2 The Funding Cliff:

Much of the current modernization effort is funded by temporary COVID-19 relief money. Public health leaders warn of an impending “funding cliff” when these dollars run out. Without a committed transition to sustained, predictable base funding, the hard-won gains in data infrastructure and workforce could evaporate, returning the system to its pre-pandemic fragility. The shift from crisis funding to foundational funding is critical.

4.3 Addressing Health Equity as a Core Function:

The pandemic laid bare stark racial and socioeconomic health disparities. Black, Hispanic, and Native American communities experienced significantly higher rates of infection, hospitalization, and death. The reshaped infrastructure must explicitly embed health equity into its core operations. This means disaggregating data by race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status; directing resources to the most vulnerable communities; and ensuring that all public health communication is accessible and culturally relevant.

4.4 Preparing for “Disease X”:

The ultimate test of the reshaped infrastructure will be the next pandemic. Whether it’s another coronavirus, a novel influenza strain, or the hypothetical “Disease X,” the system must be nimble enough to respond to an unknown threat. This requires not just specific countermeasures but a resilient, adaptive, and trusted system that can surge capacity, communicate effectively, and protect the most vulnerable from day one.

Conclusion: A More Resilient, but Not Yet Invulnerable, Future

The COVID-19 pandemic was a traumatic and costly instructor, but its lessons are indelible. It forced a nation to look in the mirror and acknowledge the decay in its public health foundations. In the years since, a profound reshaping has begun. The massive investment in data modernization, the overhaul of the strategic stockpile, and the renewed focus on the workforce are all positive and necessary developments.

However, the job is far from complete. The new infrastructure is being built on contested ground, challenged by political polarization, the threat of evaporating funds, and deep-seated societal inequities. The final, and most crucial, element of the post-pandemic landscape is not technological or logistical, but societal: the restoration of public trust. A public health system is only as strong as the people’s willingness to follow its guidance. Building that trust requires transparency, consistency, humility, and a relentless commitment to equity. The reshaping of America’s public health infrastructure is a story still being written, and its conclusion will determine the nation’s fate when the next inevitable threat emerges.

Read more: The Cost of Caring: Navigating the US Healthcare System for Mental Wellness

FAQ Section

Q1: What is the single biggest change to the US public health system after COVID-19?

A: The most significant structural change is the massive Data Modernization Initiative (DMI) led by the CDC. It aims to move the country from a slow, fragmented, and outdated data collection system to a seamless, real-time, and interoperable network. This is considered the backbone for all future preparedness and response efforts.

Q2: I keep hearing about a “funding cliff” for public health. What does that mean?

A: The “funding cliff” refers to the imminent expiration of temporary federal funds from COVID-19 relief packages (like the American Rescue Plan). These funds are currently paying for thousands of public health workers, new data systems, and other modernization efforts. If Congress does not act to replace this with sustained, baseline funding, states and local health departments could be forced to lay off staff and abandon new programs, erasing the progress made since 2020.

Q3: How has the Strategic National Stockpile changed?

A: The SNS has evolved from a static warehouse of supplies to a more dynamic and strategic reserve. Changes include:

- Smarter Inventory: Using data to predict needs and rotate stock to prevent expiration.

- Diversified Supply Chains: Investing in domestic production and multiple suppliers for critical items to avoid overseas shortages.

- Flexible Manufacturing: Stockpiling raw materials and investing in platform technologies (like mRNA) that can be quickly adapted for new threats.

Q4: Why did public health messaging seem so confusing during the pandemic?

A: The confusion stemmed from several factors:

- Novel Virus: Scientific understanding of the virus evolved rapidly, so guidance necessarily changed (e.g., on masks and surface transmission).

- Decentralized System: Different messages came from federal, state, and local leaders, creating inconsistency.

- Misinformation: The rapid spread of false information on social media sowed doubt and confusion.

- Communication Missteps: Public health agencies have acknowledged the need to better communicate scientific uncertainty and the evolving nature of evidence.

Q5: What can be done to restore public trust in health institutions like the CDC?

A: Restoring trust is a long-term process that requires:

- Transparency: Being open about what is known, what is not known, and the decision-making process.

- Consistency and Coordination: Aligning messages across different levels of government as much as possible.

- Humility: Acknowledging past mistakes and communicating with empathy.

- Community Engagement: Partnering with trusted local community leaders and organizations to disseminate information.

Q6: Are we better prepared for the next pandemic?

A: The U.S. is operationally more prepared due to modernized data systems, a better-equipped stockpile, and a more experienced (though still stressed) workforce. However, we are politically and socially more vulnerable due to deep polarization, eroded trust, and laws in some states that limit public health powers. Our technical capabilities have improved, but our social cohesion for a unified response has weakened.