Introduction

In the landscape of American public health, a silent and persistent epidemic continues to surge, often overshadowed by more immediate crises yet eroding the nation’s health foundation with alarming consistency. This is the epidemic of sexually transmitted infections (STIs). For years, the United States has held the dubious distinction of having the highest rate of STIs among all developed nations. The situation is not stabilizing; it is accelerating. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), reported cases of syphilis, gonorrhea, and chlamydia have reached record-breaking levels for multiple consecutive years, painting a picture of a public health crisis that demands urgent and multifaceted attention.

Termed a “silent” epidemic, many STIs can be asymptomatic for extended periods, leading to unintentional transmission and delayed treatment, which can result in severe long-term consequences including infertility, ectopic pregnancy, chronic pain, and increased susceptibility to HIV. The rising rates are not a simple story of individual behavior but a complex tapestry woven from threads of systemic failure, social stigma, scientific challenge, and evolving social dynamics.

This article provides a deep and authoritative analysis of the rising rates of STIs in the American population. We will dissect the latest epidemiological data, explore the root causes driving the surge—from crumbling public health infrastructure to the shadow of antimicrobial resistance—and examine the disproportionate impact on marginalized communities. Finally, we will outline a path forward, highlighting evidence-based strategies for prevention, screening, and treatment that are crucial to reversing this dangerous trend.

Part 1: The Statistical Landscape – A Nation in Crisis

To understand the scope of the problem, one must first examine the cold, hard numbers. The CDC’s annual Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance Report is the primary source of this data, and its recent editions have consistently sounded alarms.

Chlamydia: The Prevalent Peril

- The Numbers: Chlamydia remains the most commonly reported notifiable disease in the United States. In the latest data, over 1.6 million cases were reported, a figure believed to be a significant undercount due to its often asymptomatic nature.

- The Demographics: It disproportionately affects young people. Nearly two-thirds of all reported cases are among adolescents and young adults aged 15-24. The biological factors—specifically, the susceptibility of the cervical cells in young women—combined with behavioral and social factors, create a perfect storm for transmission.

- The Danger: When left undiagnosed and untreated, chlamydia can have devastating consequences for women, leading to pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), which can cause irreversible damage to the fallopian tubes, uterus, and surrounding tissues. This is a leading cause of infertility and ectopic pregnancy.

Gonorrhea: The Evolving Adversary

- The Numbers: Cases of gonorrhea have been climbing steadily, with over 700,000 reported cases annually. The rate of increase has been particularly sharp among men.

- The Demographics: Like chlamydia, it is most common in young adults (15-24). However, the rising rates among men, particularly men who have sex with men (MSM), are a major point of concern.

- The Danger: Gonorrhea is notorious for its ability to develop resistance to antibiotics. It has progressively resisted nearly every class of drug ever used to treat it. The CDC now recommends a single effective therapy: a 500mg intramuscular shot of ceftriaxone. The specter of extensively drug-resistant (XDR) gonorrhea, potentially untreatable with current antibiotics, is a genuine and terrifying threat to global public health.

Syphilis: The Great Mimic’s Resurgence

The story of syphilis is perhaps the most dramatic and concerning of all.

- The Numbers: After being on the verge of elimination in the year 2000, syphilis has made a devastating comeback. Total cases of syphilis (all stages) have skyrocketed, increasing by over 80% in a recent five-year period. The most alarming rise is seen in congenital syphilis.

- Congenital Syphilis: A Preventable Tragedy: Congenital syphilis occurs when a mother passes the infection to her baby during pregnancy. It can result in stillbirth, neonatal death, premature birth, and severe lifelong physical and neurological problems for the child. Reported cases of congenital syphilis have increased by a staggering more than 300% in the last decade. Each case is a sentinel event, representing a catastrophic failure in the public health system, as it is almost entirely preventable with timely testing and treatment during pregnancy.

The Human Papillomavirus (HPV) and Herpes

While chlamydia, gonorrhea, and syphilis are nationally notifiable diseases, other STIs like Human Papillomavirus (HPV) and herpes simplex virus (HSV) are incredibly common and contribute significantly to the overall burden.

- HPV: HPV is the most common STI in the U.S., with nearly everyone who is sexually active getting it at some point in their lives. While most infections clear on their own, persistent infection with high-risk strains can lead to cancers of the cervix, vulva, vagina, penis, anus, and oropharynx (back of the throat). The introduction of the HPV vaccine represents one of the most powerful tools in modern public health—a safe and effective method to prevent multiple types of cancer.

Part 2: The Root Causes – A Multifaceted Public Health Failure

The rising STI rates are not the result of a single cause but a confluence of interconnected factors that have created a fertile ground for their spread.

1. Erosion of Public Health Infrastructure

The backbone of STI prevention has been chronically underfunded for decades.

- Clinic Closures: A network of dedicated STI clinics once provided confidential, low-cost, and expert care across the country. Since 2003, more than half of these local health department clinics have closed or reduced their hours, victims of budget cuts and shifting priorities. This has created “STI deserts,” where individuals have limited access to testing and treatment.

- Diversion of Resources: The relentless cycle of public health crises, from H1N1 to Zika and most notably the COVID-19 pandemic, has forced health departments to divert already-strained resources away from STI prevention. Contact tracers for syphilis were reassigned to COVID-19, screening programs were paused, and public awareness campaigns stalled.

2. The Stigma and Shame Factor

Stigma remains one of the most powerful and insidious barriers to STI prevention.

- Barrier to Testing and Disclosure: The deep-seated social shame associated with STIs discourages people from getting tested, from openly discussing sexual health with partners, and from seeking treatment in a timely manner. This fear of judgment can be more powerful than the fear of the disease itself.

- Impact on Healthcare Encounters: Stigma can also exist within the healthcare system. Patients may feel judged by providers, leading them to avoid future sexual health discussions. Culturally competent and non-judgmental care is not universal.

3. Socioeconomic Determinants and Health Inequities

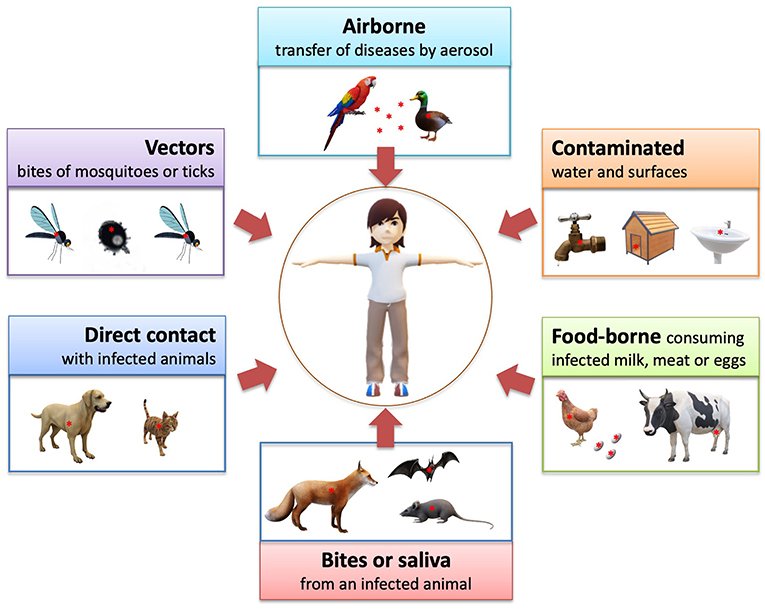

STIs are not distributed equally across the population. They disproportionately affect racial and ethnic minority groups, young people, men who have sex with men, and people living in poverty. These disparities are not due to individual behavior alone but are driven by systemic inequities.

- Poverty and Access: Poverty is strongly correlated with higher STI rates. Factors include limited access to quality healthcare, lack of transportation to clinics, inability to take time off work for appointments, and living in areas with poorer health education and fewer preventive services.

- Systemic Racism and Historical Trauma: Historical abuses, such as the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, have bred a deep and justified distrust of the medical system among many Black communities. This legacy, combined with ongoing systemic racism in healthcare (including implicit bias and discriminatory practices), creates significant barriers to care and contributes to worse health outcomes.

- Focus on Vulnerable Populations:

- Men Who Have Sex with Men (MSM): MSM face a disproportionately high burden of STIs, particularly syphilis and gonorrhea. This is influenced by complex sexual networks, biological susceptibility for certain transmission routes, and ongoing stigma that can limit healthcare engagement.

- Adolescents and Young Adults: This group has a combination of biological susceptibility, higher rates of partner change, and often poor access to confidential sexual healthcare without parental consent.

4. The Digital Age: Dating Apps and Sexual Networks

The advent of dating apps and social media has fundamentally changed how people meet sexual partners.

- Increased Efficiency: Apps can dramatically increase the efficiency of finding partners, potentially leading to larger sexual networks and more concurrent partnerships, which can facilitate the rapid spread of STIs.

- Anonymity and Disclosure: While apps can be used to facilitate open conversations about sexual health, the perceived anonymity can also reduce the perceived need for such discussions or for disclosing STI status.

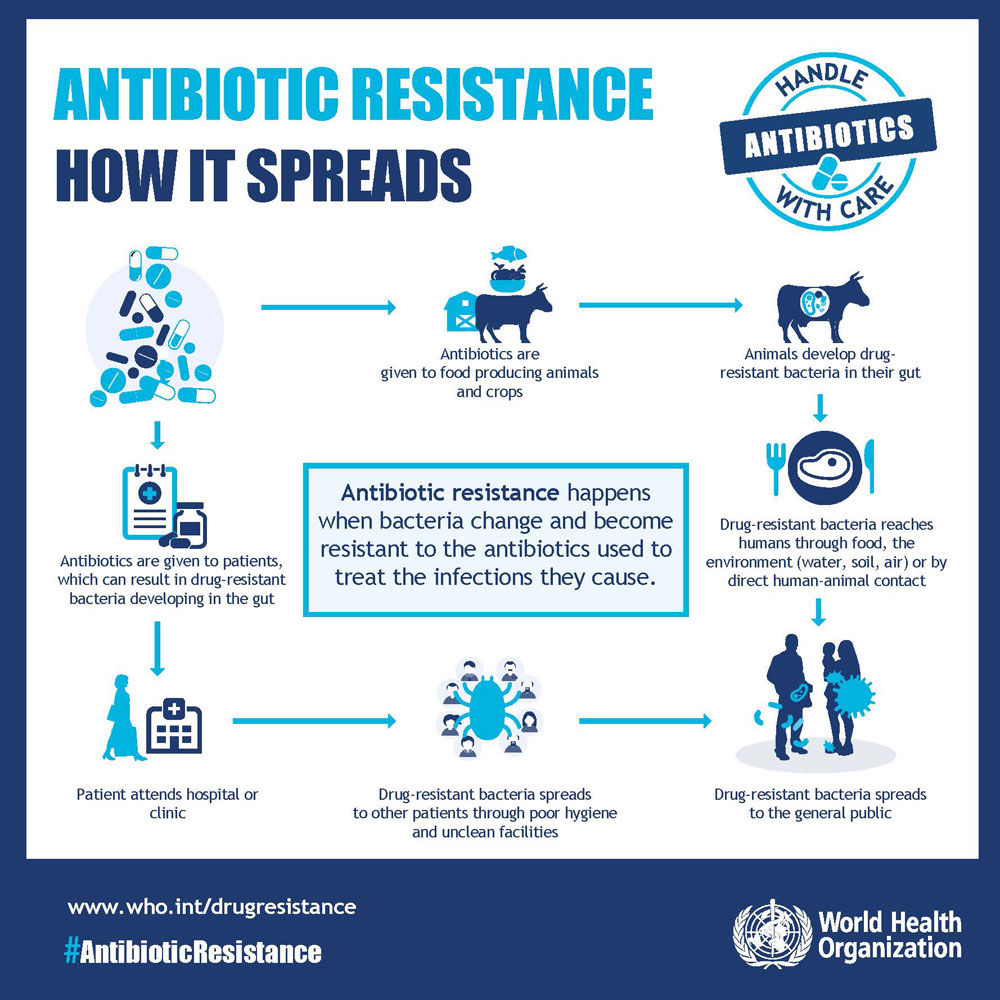

5. The Crisis of Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR)

This is particularly acute for gonorrhea. Neisseria gonorrhoeae is a “smart bug” that has developed resistance to every antibiotic used against it. The current last-line treatment, ceftriaxone, is showing signs of reduced susceptibility in some parts of the world. The pipeline for new antibiotics is dry, as it is not a profitable venture for most pharmaceutical companies. The emergence of extensively drug-resistant (XDR) or untreatable gonorrhea is a looming nightmare scenario.

Read more: Measles Comeback: Are We Facing a Public Health Crisis in 2025?

Part 3: The Path Forward – A Blueprint for Reversal

Reversing the tide of the STI epidemic requires a paradigm shift—from a reactive model of treatment to a proactive, robust, and equitable system of prevention and care. The following strategies are critical components of a national solution.

1. Rebuilding and Modernizing Public Health Infrastructure

- Sustainable Funding: Congress and state legislatures must commit to sustained, increased funding for public health, specifically earmarked for STI prevention. This includes reopening shuttered clinics, extending hours, and hiring and training a dedicated workforce of disease intervention specialists.

- Innovative Service Delivery: We must meet people where they are.

- Telehealth and E-Consults: Expand telehealth for STI counseling, prescription of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV, and management of certain conditions.

- Express Clinics and Vending Machines: Implement express STI testing clinics and even install vending machines that dispense at-home test kits or medications like doxycycline PEP in high-risk settings like college campuses and LGBTQ+ centers.

- Integration of Services: Integrate STI screening into other common healthcare touchpoints, such as primary care visits, emergency departments, mental health clinics, and substance use treatment programs.

2. Destigmatizing Sexual Health Through Education and Communication

- Comprehensive, Medically Accurate Sex Education: The U.S. must move beyond the failed experiment of abstinence-only education. Evidence-based, comprehensive sex education that includes information on condom use, consent, and STI prevention has been proven to delay sexual initiation and increase protective behaviors when adolescents become sexually active.

- Public Awareness Campaigns: Launch large-scale, destigmatizing public health campaigns that normalize conversations about sexual health. These campaigns should be inclusive of all genders, sexual orientations, and racial/ethnic backgrounds.

- Healthcare Provider Training: Mandate training for healthcare providers on cultural competency, implicit bias, and how to take a comprehensive sexual history in a non-judgmental and inclusive manner.

3. Embracing Biomedical and Technological Innovations

- Expanding the Toolbox: Doxycycline PEP (Doxy-PEP): Recent groundbreaking research has shown that taking a single 200mg dose of doxycycline within 72 hours after condomless sex can significantly reduce the incidence of chlamydia, gonorrhea, and syphilis among high-risk groups like MSM and transgender women. The CDC has now issued guidelines on its use. This is a powerful new prevention tool that must be implemented widely and ethically.

- At-Home Testing Kits: The FDA approval and insurance coverage of at-home STI test kits can revolutionize screening by increasing access, privacy, and convenience. Users can collect their own samples (urine, swabs, finger-prick blood) and mail them to a lab, receiving results electronically.

- The Undervalued Power of Vaccination:

- HPV Vaccine: We must redouble efforts to increase HPV vaccination rates in both boys and girls. The goal is to achieve the Healthy People 2030 target of 80% vaccination coverage. This is a cancer-preventing vaccine.

- Research for New Vaccines: Increased investment is needed to develop vaccines for other STIs, particularly for gonorrhea and chlamydia, which are showing promising early-stage research.

4. Addressing the Syndemic and Root Causes

STIs do not exist in a vacuum. They are part of a “syndemic,” where multiple epidemics (STIs, HIV, substance use, mental health) interact synergistically, exacerbated by social inequities.

- A Holistic Approach: STI prevention programs must be integrated with mental health services, substance use treatment, and housing assistance. Addressing the underlying social determinants of health—poverty, racism, homophobia, and lack of education—is not a separate issue; it is fundamental to STI control.

- Community-Led Interventions: Fund and empower community-based organizations, particularly those led by and for Black, Latino, and LGBTQ+ communities, to design and implement culturally resonant prevention and outreach programs. Trusted messengers are essential for rebuilding trust.

Conclusion

The relentless rise of sexually transmitted infections in the United States is more than a statistical anomaly; it is a stark reflection of systemic neglect, entrenched stigma, and profound health inequities. The solutions are known, evidence-based, and within our grasp. They require not just medical interventions but a societal commitment to prioritizing sexual health as a fundamental component of overall well-being.

This entails a renewed investment in our public health infrastructure, a courageous national conversation to dismantle stigma, and a steadfast dedication to health equity that leaves no community behind. The silent epidemic can be countered, but it demands our voice, our resources, and our unwavering attention. The health and future of millions of Americans depend on the choices we make today.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q1: I don’t have any symptoms. Do I still need to get tested for STIs?

- A: Yes, absolutely. Many common STIs, like chlamydia, gonorrhea, and HPV, are often asymptomatic, especially in the early stages. You can have an infection and unknowingly transmit it to a partner. Regular screening is the only way to know your status and protect your health and the health of your partners. The CDC recommends annual screening for sexually active women under 25, men who have sex with men, and others at increased risk.

Q2: How often should I get tested, and for what?

- A: The frequency and type of testing depend on your sexual behavior, number of partners, and other risk factors. A general guideline:

- All sexually active adults: Discuss testing with your healthcare provider at your annual check-up.

- Sexually active women under 25: Annual test for chlamydia and gonorrhea.

- Men who have sex with men (MSM): At least annual testing for syphilis, chlamydia, gonorrhea (of the throat, rectum, and urine), and HIV. Some may benefit from more frequent (e.g., 3-6 month) testing.

- Pregnant people: Testing for syphilis, HIV, and hepatitis B early in pregnancy, with repeat testing for syphilis and others as needed.

- Anyone with a new partner or multiple partners: Get a full-panel test before and after new partners.

Q3: I tested positive for an STI. How do I tell my partner(s)?

- A: This can be difficult, but it’s a critical responsibility for their health and yours. Be direct, calm, and non-accusatory. You can say something like, “I care about you and your health, so I need to let you know that I’ve been diagnosed with [STI name]. I recommend you get tested as well.” Many health departments offer partner notification services (sometimes called Partner Services or Disease Intervention Specialists) that can confidentially inform your partners of their potential exposure without revealing your identity.

Q4: What is Doxy-PEP, and should I be using it?

- A: Doxy-PEP (Doxycycline Post-Exposure Prophylaxis) involves taking a single 200mg dose of the antibiotic doxycycline within 24-72 hours after having condomless oral, anal, or vaginal sex. Current CDC guidelines recommend it be considered for men who have sex with men (MSM) and transgender women who have had at least one bacterial STI (chlamydia, gonorrhea, or syphilis) in the past 12 months and are at ongoing high risk. It is not currently recommended for cisgender women or other groups, as more research is needed. It is crucial to discuss this with a healthcare provider to see if it’s right for you, as it requires a prescription and does not protect against other STIs like HIV or herpes.

Q5: I’ve had the HPV vaccine. Do I still need Pap tests?

- A: Yes. The HPV vaccine is highly effective at preventing infection from the high-risk HPV strains that cause most cervical cancers. However, it does not protect against all cancer-causing HPV strains. Therefore, it is essential that women and people with a cervix continue to follow recommended cervical cancer screening guidelines, which include regular Pap tests (or Pap smears) and/or HPV tests as advised by their healthcare provider. The vaccine and screening together provide the best protection.

Q6: Where can I get confidential and low-cost STI testing?

- A: Several resources are available:

- Local Health Departments: Search for “[Your County] Health Department STI Clinic.”

- Planned Parenthood: Provides a wide range of sexual health services on a sliding fee scale.

- Community Health Centers: Offer comprehensive care, including STI testing.

- At-Home Testing Kits: Companies like Everlywell, LetsGetChecked, and Nurx offer FDA-authorized kits you can order online.

- Your Primary Care Provider: Your regular doctor can order STI tests.

Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only and is based on current guidelines from authoritative bodies like the CDC. It is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition or before starting any new treatment.

Read more: The Return of RSV, Flu & Respiratory Coinfections: What to Expect This Season